A call to counter antisemitism

By Justin Kirschner

When you look at the FBI hate crime statistics for Ohio, it would be easy to assume that the Jewish population has it rather good.

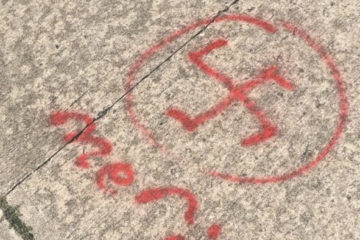

In 2020, the latest year for which figures are available, there were 10 anti-Jewish crimes reported. Most were for damage or vandalism of property. There were no physical assaults tied to antisemitism.

Yet, at the same time, we have to deal with the likes of Matthew Slatzer, a Canton ex-con who was seen at a 2020 anti-Covid mandate rally at the Statehouse in Columbus holding a sign depicting a rat and the Star of David with the words, “The Real Plague.”

Slatzer had also walked into a store with a hatchet and sword and asked for directions to Kent State University, where he heard “there were a lot of Jews.”

You could write that off as the fulminations of an extremist rather than a sickness taking hold of society. But many Jews I know and work with feel something is different, that something is off.

There is a palpable sense of unease that may not have existed even a few years ago, before White supremacists in Charlottesville in 2017 bellowed “Jews will not replace us.”

Indeed, Ohio has the second-largest number of extremist anti-government groups, as documented by the Southern Poverty Law Center. Not all are racist or antisemitic, but there are enough that traffic in conspiracy theories that inevitably scapegoat Jews for them to be a cause of concern.

Moreover, when the American Jewish Committee last year released the findings from its latest State of Antisemitism in America survey, we learned that some 90 percent of Jews surveyed believe antisemitism is a problem. Nearly 25 percent said they were the victim of some kind of antisemitic incident.

Perhaps the most troubling revelation: some 39 percent of Jews said they had altered their behavior to conceal the fact they were Jewish. That included not wearing a kipah or a Star of David in public and posting or commenting about pro-Israel content on social media. And it was younger Jews—52 percent —who were the ones most likely to change their behavior.

That is evident every time we walk into a synagogue, where armed security accompanies our worship. The emotional scars from the Tree of Life massacre in Pittsburgh in 2018 or the Chabad House in Poway, Calif. the following year may never heal.

When a gunman took hostages at a synagogue in Colleyville, Texas in January, it was easy to assume the worst.

That everyone but the gunman made it out alive was as much a surprise to many as it was a relief.

So, where does that leave us in Ohio? Gov. Mike DeWine has taken a zero-tolerance approach to antisemitism. He issued an order for the state to recognize the International Holocaust Remembrance Alliance’s working definition of antisemitism, which he noted is a “disturbing problem in American society, including here in Ohio.”

However, the IHRA definition, while important and recognized globally, is nonbinding and carries no legal weight.

So, by necessity, fighting antisemitism is a top priority at the American Jewish Committee, where I serve as Cincinnati regional director. Put simply, we are tired of playing defense.

That is why we conduct antisemitism trainings throughout the country, including with government officials, law enforcement, the media, including Cincinnati-based Scripps Media, and the public. For many, a presentation on antisemitism at the Jewish Cultural Festival at Temple Israel in Dayton was a revelation, to say the least.

It is why we put out Translate Hate, a comprehensive downloadable glossary of antisemitic terms, which explains why certain phrases and words are anti-Jewish. Too often, we find that people grew up hearing terms like “Jew down” or “poisoning the well” without realizing why they are so hurtful.

It is also why AJC co-founded the Muslim-Jewish Advisory Council in 2016, a national initiative with regional relationship-building activities. Because we know the more that faiths understand and respect each other, the more we can stand in solidarity against hate and prejudice.

During the hostage standoff in Colleyville, imams were at the sides of Jewish leaders to show the support at a time when a Muslim was holding hostages at gunpoint.

Colleyville is an example of why AJC places a premium on its relationships with law enforcement on the local, state, and national levels.

To have the best chance at tackling antisemitism, we must first know the extent of the problem. There were only 10 anti-Jewish crimes reported in Ohio in 2020. Emphasis on reported. Because numerous studies have found that hate crimes, be they motivated by religion, race, ethnicity or sexual orientation, are notoriously under-reported by police and victims.

You’re only as good as your information. The FBI relies on statistics from the state. But as WKEF-TV in Dayton reported last year, only 547 of the state’s nearly 900 law enforcement agencies submitted data to the Ohio Office of Criminal Justice Services.

It strains credulity to assume that hundreds of police departments had no hate crimes occur, especially when Ohio’s hate crime rate in 2018 was nearly double the national average.

Police must do a better job of partnering with affected communities, identifying hate crimes, and properly document them so the full extent of the problem can be known.

We know what law enforcement should do. What should you do?

• Speak out. If you see an antisemitic incident or are the victim of one, don’t just tell your friends or rabbi. Tell the police or contact your local FBI office to report a hate crime. There may be other similar incidents. The more they know, the better they are able to catch a perpetrator and inform policy using the data they have.

• Learn more. Many of us know antisemitism when we hear or see it. But knowing how or why is essential to stopping it or educating others about why it is wrong. AJC’s Combating Antisemitism collection, available on the AJC website, is an excellent resource. I guarantee you will learn something new.

• Take action. There are a few core steps that you can take to help alleviate antisemitic concerns in your community. Help people understand diverse Jewish peoplehood and that antisemitism is more than just a religious bigotry; strive to include antisemitism education as part of your school, organization, or workplace’s DEI efforts, stand in solidarity with other minority communities, and ensure your elected officials know this is a priority for you and for that matter, the sanctity of our democracy.

As much as anything, always be Jewish and proud. Antisemitism may be the world’s oldest hatred. But we will keep finding new ways to beat it back. We will not run and hide. No more. Never again.

Justin Kirschner is regional director of the American Jewish Committee in Cincinnati.

To read the complete August 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.