Beth Abraham @ 125

Dayton’s Conservative synagogue to kick off year of celebrations with American Jewish history Prof. Jonathan Sarna

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

The scholar who wrote the book on American Jewish history will officially kick off Beth Abraham Synagogue’s 125th anniversary celebration year, March 29 and 30.

Dr. Jonathan Sarna, professor of American Jewish History at Brandeis University, director of the Schusterman Center for Israel Studies at Brandeis, and author of the seminal book, American Judaism: A History, will lead Beth Abraham’s American Jewish Experience Shabbat with three lectures over the weekend.

According to JTA, which has described Sarna as a “rock star Jewish historian,” students at the Reform movement’s Hebrew Union College-Jewish Institute of Religion, the Conservative movement’s Jewish Theological Seminary, and Orthodoxy’s Yeshiva University all study Sarna’s American Judaism.

“I hope to put some of the history of the congregation into the context of American Judaism,” says Sarna, who is also chief historian of the National Museum of American Jewish History in Philadelphia.

“I’d like to say something about what made Beth Abraham special for so many years,” he adds. “Even in my years, they had a youth choir and that was nationally known, and really put this congregation on the map for a lot of people.”

He’ll also talk about how Beth Abraham’s movement from Orthodox to Conservative Judaism matched what went on at numerous Jewish congregations across the United States.

“It was the desire to be traditional while at the same time accommodate American religious norms,” he says. “It’s what the Conservative movement called tradition and change. And that especially played out often in synagogue seating or as they might have called it family seating.”

The Litvishe shul

Beth Abraham’s founders — essentially peddlers who were fairly new to Dayton — established the synagogue on July 25, 1894 as a Litvak (Lithuanian) Orthodox Jewish congregation, distinct from Beth Jacob Synagogue, Dayton’s Orthodox Russishe (Russian) Jewish congregation, and the Reform B’nai Yeshurun (now Temple Israel), which catered to German Jews.

Two months later, Beth Abraham’s founders purchased an eighth of an acre of land in Van Buren Township (now in Kettering), immediately to the west of B’nai Yeshurun’s cemetery, for its own cemetery.

Sarna explains why Lithuanian Jews would want to establish their own synagogue.

“There were a couple of things. First of all, there was a matter of rite,” he says. “The Lithuanians very much followed in the footsteps of Elijah of Vilna (1720-1797). They were tremendously proud of the man known as the Genius, the Vilna Gaon, and they studied him. They emulated him. If he said to do something, they did it.”

Sarna emphasizes that for an immigrant, religion is an anchor in a sea of change.

“You wanted a synagogue that reminded you of the way things were done back home,” he says. “And if you came from Lithuania, those home customs were different than if you came from other places within the Russian Empire.”

The next generation after these immigrants couldn’t begin to understand those differences, Sarna adds.

“When I tell my students that it was once considered an intermarriage for a Litvak to marry a Galitzianer — first of all, you can’t find a map of where Galicia was,” he says. “They think it’s in Spain. Today it’s all divided: part of it’s in Ukraine and part is in the Czech Republic. It was intractable, insurmountable, almost genetic. When blood donations began, there were debates: should I be giving or getting blood from a Galitzianer if I’m a Litvak? And today, who remembers such things? We roar with laughter that once upon a time that was (considered) an intermarriage.”

He sees this example as a sign of hope about other divisions in Judaism today and what Jews will think a century from now.

“History reminds you that small matters take on significance. They become huge symbolic issues.”

From the East End to Dayton View

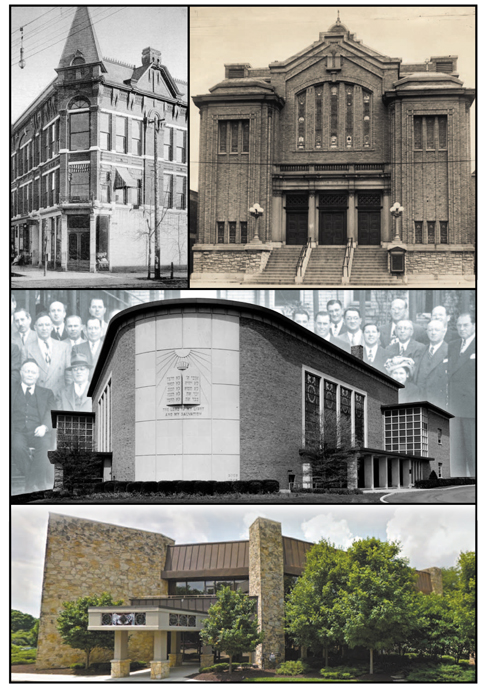

Beth Abraham’s first known location is listed in the 1895 Williams’ Dayton City Directory as in the building at the southeast corner of Fifth Street and Wayne Avenue, in the heart of the East End, Dayton’s Eastern European Jewish neighborhood of the time.

After 1902, Beth Abraham moved a few blocks south on Wayne Avenue to a wood-frame building which was washed away in the Great Flood of 1913. Five years later, congregants dedicated a brick building, the Wayne Avenue Synagogue, at the site.

However, Jewish migration from the East End — and among German Jews who lived downtown — had already begun. Those who could afford to, began moving to Dayton View, which was on higher ground and welcomed Jews.

But Dayton View’s Jews had a substantially farther walk across the river and back to the East End to worship at their Orthodox shuls on the Sabbath and holy days, when driving was prohibited. Children had a much farther walk to Hebrew school as well.

In 1922, the Dayton View Synagogue Center, Dayton’s first Conservative Jewish institution, opened its doors on Cambridge Avenue. Unlike at Beth Jacob and Beth Abraham, men and women could sit together in this setting, which still used an Orthodox prayer book.

By then, Conservative Judaism — which adheres to halacha (Jewish law) in light of historical developments — occupied a centrist position in American Judaism, to the religious left of Orthodoxy and to the religious right of Reform Judaism.

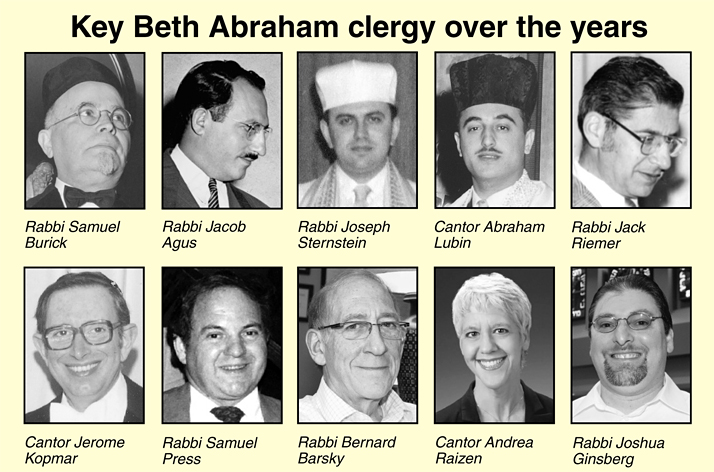

It was in 1941 when Beth Abraham, Beth Jacob, and Dayton View Synagogue entered talks about merging the three congregations. A year later, the nascent entity hired Rabbi Jacob Agus, who was ordained at Yeshiva University (Orthodox), to lead it.

When it became apparent the new organization would not maintain Orthodoxy, Beth Jacob changed course and opened its own synagogue on Kumler Avenue in Dayton View in 1945.

Agus joined the Conservative movement’s Rabbinical Assembly in 1945 (he would become an important theologian in the movement) and led Beth Abraham United Synagogue, the merger of Beth Abraham and Dayton View synagogues, which dedicated its building at Salem Avenue and Cornell Drive in Dayton View in 1949.

An accommodation to Beth Abraham’s Orthodox members in the early years of the merger appears to have been that Orthodox services were available in the synagogue’s small chapel.

Across the river again

Following the migration of the area’s Jewish community to the suburbs south of Dayton, Beth Abraham moved in 2008 to what had been NCR’s international training facility, Sugar Camp, in Oakwood.

For much of the 20th century, Jews were generally not welcome to live in Oakwood.

Now, with approximately 150 Jewish households, Oakwood is an anchor of the Dayton area’s Jewish community, with Hillel Academy Jewish day school on the third floor of Beth Abraham, the Miami Valley Mikvah also at Sugar Camp, and Chabad to the south, on Far Hills Ave.

And Conservative Judaism here continues to navigate pronounced challenges of tradition and change, just as it does across the country.

A generation ago, women were accepted as worship leaders and clergy. Today, the movement welcomes those in intermarriages and those in the LGBTQ community.

LGBTQ people can be clergy, and Conservative clergy can officiate at LGBTQ weddings.

The movement still stands firm against allowing Conservative clergy to officiate at intermarriages, even though as of October 2018, they can attend interfaith weddings.

In 2013, the Pew Research Center reported that 18 percent of U.S. Jews identified with Conservative Judaism; its estimated peak was 41 percent in 1971.

After kiddush lunch on March 30, Sarna will discuss future trends in American Judaism, at Beth Abraham’s request. He’ll present a cyclical rather than linear view of history.

“I think too many American Jews imagine that the history is somehow predetermined and all they need is some smart professor to come and tell you what will happen,” he says. “And I always give the message that we shape our history. We make history. That’s a very important message, especially for younger people to hear. And in my view, we’ve made our history time and time again in our country.”

Beth Abraham’s American Jewish Experience Shabbat with Prof. Jonathan Sarna

- Friday, March 29: Kabalat Shabbat Service with Dayton Jewish Chorale at 5:30 p.m. Shabbat dinner at 6:30 p.m. followed by talk, Old Faith – New World. Dinner is $18 per adult, payable by March 22. No charge for ages 12 and under; babysitting available.

- Saturday, March 30: Shabbat services at 9 a.m. with the sermon, Revitalization – Successes and Challenges. Kiddush lunch at noon followed by talk, What’s Next?

- R.S.V.P. for Friday dinner and/or Saturday kiddush lunch by March 22 to 293-9520.

To read the complete March 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.