A heritage of hope

Our Dual Heritage Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Prevented from gathering — or even extensive shopping — for Passover seders this year due to Covid-19, Jews across the country were at first despairing. But hope doesn’t die so easily.

Synagogues, caterers, Jewish organizations, and individuals began delivering seder meals, offering website-based Passover prep tutorials, coaching Passover cooking from home kitchens via YouTube, and using technology to create seder experiences, offering hope to both the inexperienced and those celebrating alone.

A Raleigh, N.C news station featured a couple who rose to the challenge, inviting a larger-than-usual crowd of 40 friends and family in six time zones around the world to their virtual Passover seder.

In Bluffton, S.C., dozens of non-Jewish neighbors responded when a sequestered woman, unable to get her Passover groceries delivered in time, used the Nextdoor neighborhood app to ask for help. Everything from horseradish to flowers showed up on her doorstep, and her hoped-for seder became a reality.

What is hope? In the Jewish worldview, hope isn’t an instinct; it’s a value and therefore a choice.

“Hope is the faith that with our efforts, we can help make things better,” explains Rabbi Michael Marmur. This unique perspective is founded in the Hebrew Bible.

In contrast, English dictionaries often equate hope with optimism, a positive but passive mental attitude that outcomes of events or experiences will be favorable.

Interestingly, there is no native Hebrew word for optimism; the Hebrew word optimiyoot is a loanword from English. In Hebrew, there is only hope.

According to Marmur, there are different opinions about the origin of the word hope (tikvah), journalist Jeffrey Goldberg notes. “Some say it comes from mikvah, a ritual bath,” with hope envisioned as “a resource, a pool, a solace, and a support.”

An alternate view suggests its origin is the cord (tikva) of scarlet thread that saved Rahab and her family during Joshua’s destruction of Jericho.

“If the first meaning of the word looks to sources of support,” Goldberg concludes, “the second kind of hope is symbolized by a thin thread leading from a complicated present to a possible future.”

Hope’s origins are not only linguistic; the very notion of hope originates in the Torah.

The ancient world believed history was cyclical, a never-ending repetition of determined events like the seasons, with no meaning or goal.

Individual lives were controlled by nature, the gods, or fate, offering little possibility of human influence over the future. In such a world, hope didn’t exist.

Until Abraham. By heeding God’s call to leave his land, his birthplace, and his father’s house, Abraham repudiated the notions of cyclical, unchangeable history and human fatalism — the very foundations of ancient history, culture, and identity.

By doing so, he opened up the possibility for choice and change, linear history with an as-yet undecided future, and — as a result — hope. This hope that individual efforts can make a difference in the course of one’s life, the community, or history altogether is a notable theme that runs through the rest of the biblical story and beyond.

As a result, Judaism itself is infused with hope. Each calendar day begins with darkness followed by light, an inspiration to always look forward.

Similarly, Chanukah candlelighting increases the number of candles by one each night to bring ever more light to the darkness.

Morning blessings are reminders to bring hope to the world around us.

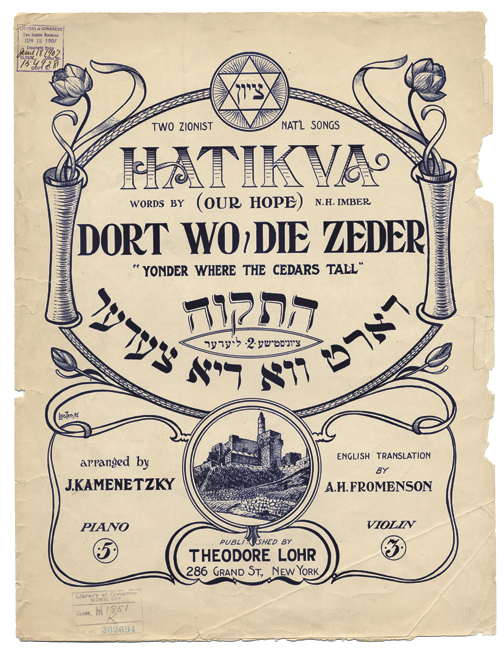

The High Holy Days bring the hope of forgiveness and new beginnings. Israel’s national anthem is Hatikvah — The Hope.

And the Talmud suggests one question asked during judgment in the afterlife will be, ”Did you live with hope?”

In the words of Rabbi Lord Jonathan Sacks, “Judaism is the voice of hope in the conversation of mankind.”

Solidly rooted in the Bible from its founding, America instinctively adopted the biblical notion of hope. The Founders encoded hope into the very DNA of America, with the Declaration’s recognition of the equality of humans before God and of its citizens’ unalienable rights to life, liberty, and the pursuit of happiness.

Inspired by the Exodus story, Abraham Lincoln pursued liberty for America’s slaves.

To the Pilgrims and Jews, America was the hope of freedom from religious and political persecution.

To dispossessed European peasants and artisans, it offered the hope of land and economic opportunity.

Across the globe, America meant hope for individual liberty, adventure, refuge from wars, pogroms, and massacres, and the possibility of being judged on character rather than class.

This heritage of hope is reflected in the titles of recently published books: Land of Hope, Still the Best Hope, and The Last Best Hope.

And it was unexpectedly acknowledged on the popular television show America’s Got Talent by a Kyrgyzstan dance crew, the South African Ndlovu Youth Choir, and the Ukrainian Light Balance Kids.

During their pre-performance interviews, each group independently expressed the same sentiment: America is the land of hope.

“(Hope) is a struggle…against the world that is, in the name of the world that could be, should be, but is not yet,” Sacks writes. “But we can only know the beginning of the story, not the end.”

The Bible. Judaism. Israel. America. Each holds hope as a value, each is actively engaged in improving the world. But as yet, we only know the beginnings of their stories.

Literature to share

Invisible as Air by Zoe Fishman. This memorable tale follows the trajectory of a couple and their son suffering the stillborn death of a long-awaited daughter. Unable to come to terms with their grief, each looks for an escape, compounding their tragedy and nearly destroying their family. Although it has a positive ending, this story’s title is foreshadowing: when we don’t let others into our lives, we become invisible as air. And being invisible can have disastrous consequences. Realistic and gripping, its message will remain with you. I couldn’t put it down.

Searching for Lottie by Susan Ross. As part of an ancestry school project, Charlie discovers her great-aunt lived in Europe in the 1940s, but it’s all a bit of a mystery. Lively and inquisitive, the very relatable Charlie sets out on a quest to unravel it. Set mostly in the present, the story is interwoven with details about European life during World War II and the history of the Holocaust in an appropriate and accessible manner for middle school readers. It’s a novel that invites discussion about the Holocaust and family histories and the storytelling that keeps the memories alive.

To read the complete May 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.