Babel a towering writer from Odessa

A Bisel Kisel

Masha Kisel, The Dayton Jewish Observer

At a recent Jewish Film Fest screening in Dayton, I picked up a pamphlet listing classic Jewish authors. There were notable omissions of many Eastern European names, which I hope to remedy by telling you about Isaac Babel, a Russian-speaking Jewish writer from Odessa.

Babel, who was born in 1894, came of age during the time of revolutionary fervor and joined the Red Army. He reached literary prominence in the early Soviet period, but despite or perhaps because of his fame, he did not survive the Stalinist purges. He was arrested on false charges of espionage and executed by a firing squad after a 20-minute trial in 1940.

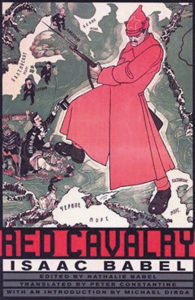

Babel’s beautifully esoteric language has earned him a place among European modernists, yet his writings are uniquely Jewish in theme. His most famous story collections, Odessa Tales and Red Cavalry, are rich in details of Jewish life in czarist and post-revolutionary Ukraine and feature unusual Jewish characters.

Odessa Tales are loosely based on Babel’s own early memories and take place in Moldavanka, the shtetl outside of Odessa where Babel was born. If you are picturing scenes from Sholem Aleichem’s Tevye stories — the basis for Fiddler on the Roof — change the channel to The Sopranos.

In Odessa Tales, Babel describes a Jewish criminal underworld ruled by Benya Krik, a young mob boss with enormous appetites and the chutzpah to satisfy them. Benya, whose last name means “yell,” is a formidable force whose influence extends even to the world of gentiles.

In one story, he tries to dissuade czarist officials from executing a pogrom before his sister’s wedding. The carnal, fearless and frightening Benya is a striking departure from the timid Jewish characters of 19th-century Russian literature.

Red Cavalry is a fictional retelling of Babel’s own experiences during the Soviet-Polish war in 1920. Many of the stories in this cycle are narrated by semi-autobiographical narrator Liutov, a Jew in the Red Army, whose revolutionary moniker means “fierce one.”

This young man “with spectacles on his nose and autumn in his heart” yearns to prove his masculinity, but cannot bear the brutality of what that entails.

The most famous in the collection is My First Goose. It begins with the narrator’s homosocial admiration for a manly Russian commander: “I marvelled at the beauty of his gigantic body.”

Concerned that the bespectacled intellectual won’t fit in with his new Cossack regiment, the commander advises Liutov to “ruin some nice lady.” The Cossacks mock and ostracize Liutov, who is desperate to earn their approval.

He and the Cossacks are housed in the hut of a depressed old (most likely Jewish) woman and although he can’t bring himself to rape her, he kills a goose in the yard by breaking its neck with his boot. This is a symbolic rape — an act of senseless cruelty that wins him an invitation to share his comrades’ pork stew “while his goose cooks.”

That night, he fulfills his dream of male bonding as he and the Cossacks sleep with their legs intertwined. But Liutov’s sleep is not peaceful. The last line of the story reads: “I had dreams — I dreamt of women — but my heart stained with murder, creaked and bled.”

That night, he fulfills his dream of male bonding as he and the Cossacks sleep with their legs intertwined. But Liutov’s sleep is not peaceful. The last line of the story reads: “I had dreams — I dreamt of women — but my heart stained with murder, creaked and bled.”

The death of a bird in My First Goose has a counterpart called The Story of My Dovecot. Set in 1905, more than a decade before the Russian revolution, it is told from the point of view of a young boy who gets into a prestigious school despite the Jewish quota and his parents reward him with two doves for his dovecot. When he buys the longed-for birds at the market, a pogrom breaks out. He encounters an antisemitic neighbor who unleashes his pent up hatred by savagely stepping on and killing one of the boy’s doves. The boy loses consciousness and wakes up the next morning to learn that his grandfather was murdered in the pogrom.

Given that both stories are semi-autobiographical, one can’t help but think of the dove-loving 11-year-old boy growing up to become the goose-killing Liutov. The little Jewish boy transforms from victim to aggressor but continues to identify with the victim, as evidenced by the dream image of the “bleeding heart” at the end of My First Goose.

In his fiction, Babel depicts the psychological dissonance felt by Jewish Bolsheviks following their fraught metamorphoses into revolutionaries. They fought for a world without czarist pogroms but committed violence against other Jews in the process.

Men like Babel who had left behind their shtetls and their Judaism to join the revolution, remained Jewish. The consciousness of being a Jew, disembodied from practice and community, persisted. Babel’s prose preserves an ephemeral moment in the history of the Jewish people. He captures the irreversible transfiguration (voluntary for some and forced upon others) of Jews into Soviet Jews.

Dr. Masha Kisel is a lecturer in English at the University of Dayton. Excerpts here are from Boris Dralyuk’s translations of Red Cavalry and Odessa Stories.

Next month: How post-revolutionary Cossacks and Jews came together in Masha’s family history.

To read the complete August 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.