Keeping histories of Ohio’s small Jewish communities alive

Upper Miami Valley & Greene Co. included in volunteer’s chronicles

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

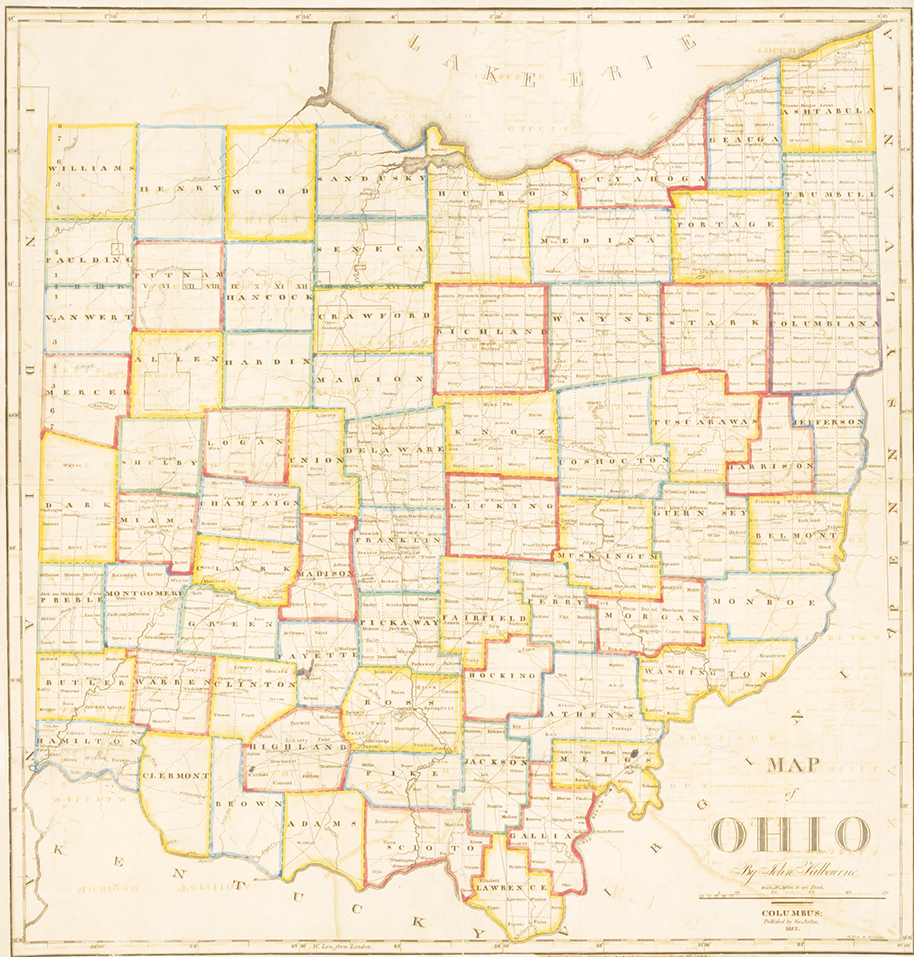

Austin Reid, 26, grew up in Lancaster, about 30 miles southeast of Columbus, in Fairfield County. The Jewish congregation there, B’nai Israel, had closed a few years before he was born.

“Like many smaller cities and towns, there was a Jewish community there at one point,” he says. “But there were still some signs of the community when I was growing up. The building was still there. It had been converted to a private residence, but you could tell it had a religious purpose at one time. There was a war memorial downtown with a Magen David (Star of David) on it in addition to a cross.”

Reid, who wasn’t born Jewish, remembers wondering what happened to the congregation, and why a Star of David would be engraved on the war memorial.

As an undergraduate history and political science major at Capital University — and a Jew by choice — he decided to find out. For his history capstone project, he researched the history of Fairfield County’s Jewish community.

When he dug into that history, he discovered there were several other Jewish communities in small Ohio towns with histories that had never been written about.

Reid is now writing his 14th and 15th histories of small Jewish communities in Ohio.

Among those he’s completed are the Upper Miami Valley and Greene County, here in the Dayton area.

From the beginning, he learned how to go about this research from The Columbus Jewish Historical Society.

After he graduated Capital University and moved to Ithaca, N.Y. — where he worked for the Hillel at Ithaca College and earned his master’s degree in public administration from Cornell University — Reid continued writing about these small Ohio Jewish communities as a volunteer project to stay connected to his home state.

“It really kicked up again during the Covid pandemic because I found myself with a lot more free time,” he says. “Some of the volunteer organizations that I would keep myself busy with weren’t really functioning, and I needed something to keep my mind off the news, and so I really picked up the project more intensely.”

The Upper Miami Valley

He learned about Piqua and the Jewish community of the Upper Miami Valley through his research on Chillicothe, because of historical family ties between the two Jewish communities.

“Piqua is a fascinating community to me because it is among the older Jewish communities in Ohio and has had a continuous presence there since 1858,” he says. “Jewish families were living in the Piqua area before 1858, but 1858 is when the congregation was founded.”

Through Temple Anshe Emeth in Piqua, Reid connected with longtime congregant, Greenville resident Eileen Litchfield.

“She was really enthusiastic about the project and helped me connect with other local people to polish up the history and have that buy-in from the local community, which was exciting.”

Litchfield describes Reid’s work for Anshe Emeth as a true gift.

“There aren’t enough adjectives to describe my delight in getting this accomplished for temple,” she says. “I have been collecting history, randomly, for 20 years, and his research blew that out of the water in a minute. I cannot tell you how ecstatic I am for his volunteering to do this.”

Litchfield added she was amazed to learn there were Jews living in Greenville in the 1850s.

“It was never a very large community,” Reid says of Piqua. “But it’s always drawn from several communities for its members. So Troy, but also Greenville and Wapakoneta and St. Mary’s had some families that would come down occasionally. It’s really always been a regional congregation. And even today, I think only one member lives in Piqua.”

He admires Anshe Emeth’s generations of hard work and leadership to maintain itself.

“I’m sure it would have just been easier to not really spend the resources to have a Jewish community, and especially now, it’s so easy to travel to Dayton from Piqua,” he says. “And in some of these communities, that’s what happened.”

Greene County

Reid came to research Greene County after he saw an article in Cincinnati’s American Israelite newspaper in 2017 about the Arnovitz family and their store in Xenia, Sol’s Store, which was in business from 1931 to 1998.

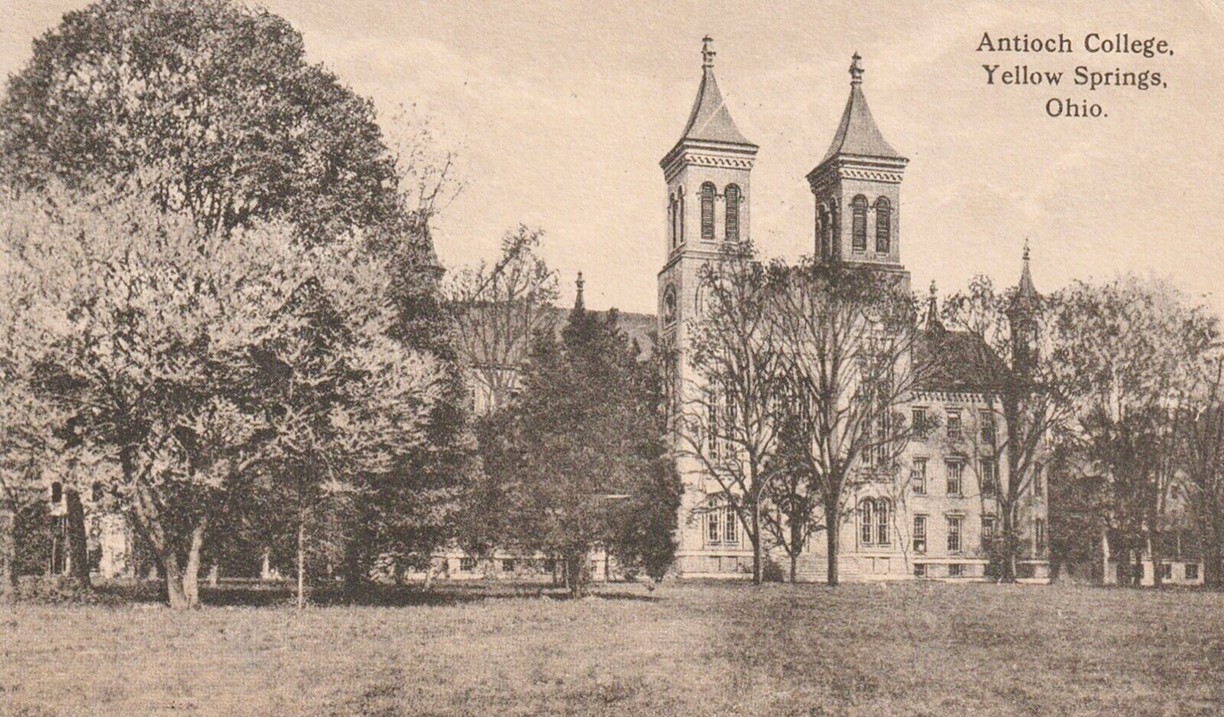

He says Greene County has a long tradition of Jewish academics, particularly connected to Antioch College.

“Even in the 1920s, Antioch College had some prominent Jewish faculty members. There was Rudolph Broda, a social sciences professor starting around 1928. And his wife, Erna, she was professor of German. And William Leiserson, an economics professor from 1926 to 1933. His work on labor relations is still influential today, because in 1933, the Roosevelt administration asked him to come to D.C. One of the things he worked on was the Railway Labor Act of 1934, and that still governs some of the labor relations and airlines and railroads today.”

In his history of Greene County, Reid identifies the earliest known Jew there as Benjamin Bruel of England, who was living in Xenia by 1870. He operated a clothing store there until 1873.

Reid’s history of Jewish Greene County comes up to the present, with the Yellow Springs Havurah, which is active to this day.

Eastern European Jews took the lead

In all the small Jewish communities in Ohio that Reid has researched, he says, German Jewish families lived there early on, but it was the great wave of Jews of Eastern Europe — who began arriving in America in the early 1880s — who provided the numbers to start viable Jewish organizations.

“Xenia is an example of that. We do have early German Jewish families. Xenia just barely got to the size of having in the 1910s a local community that was formal,” Reid says. “But at least in Xenia, it was never quite large enough to be sustainable.”

The full list of Reid’s histories of small Ohio Jewish communities comprises Ashtabula County, Athens County, Chillicothe, Coshocton, Fremont, Greene County, Lancaster, Newark, New Philadelphia, Portsmouth, Steubenville/Weirton, the Upper Miami Valley, and Zanesville. He’s also written a history of the Jews of West Virginia.

“You had these layleaders with maybe just a little more — compared with their peers, perhaps — knowledge of the religious laws and they really just carried these communities. They’d have occasional itinerant rabbis who would come through and maybe do more formal instruction, but it really was just the laypeople.”

He’s now finishing up his histories of Mansfield and Massillon, Ohio. Reid started writing about Mansfield because he heard its one Jewish congregation is moving from its 44-year-old building. “There, it was nice for some of the congregants to reflect on their memories.”

The largest of the Ohio Jewish communities he’s written about was Steubenville/Weirton, which at one time had about 1,000 Jews. The oldest he’s written about is Chillicothe; its first-known Jews date to the 1830s.

With most communities he’s written about, he knows of at least one Jewish family still living there.

“But some of the places, indeed, have not had organized Jewish life there in several decades,” he says. “One example is New Philadelphia, Ohio. The congregation there closed in the ’60s, but there are still Jewish families there.”

Outsized contributions

He was surprised to find that in a lot of these small towns, Jews served in public office well before 1900.

“You had examples of playing important roles in secular organizations like the Masons or veterans’ groups, societies.”

He highlights those contributions to economic, social, and civil life in his histories.

“While the Jewish population of these communities has never been more than 1 percent or 1.5 percent, it’s an outsized influence on hospitals in the areas, the charitable societies in the areas, helping to organize fire departments, to raise money for orphanages.”

Reid says he took on this project for two reasons.

“One, I think the mitzvah of honoring the deceased is an important one. I volunteer with a burial society, a chevra kadisha, so this is probably a related value that informs why I volunteer with the chevra kadisha and why I do these stories.”

He also believes small-town Jewish communities played an important role in Judaism becoming a more mainstream religion in the United States.

“I think after World War II, we really saw that,” he says. “Judaism didn’t always have that insider status and perhaps now we’re seeing an increase in antisemitism. The existence of these small-town Jewish communities and the fact that Jewish life had a visible presence in so many places was important for people’s understanding of Jewish life. And with that absence, there aren’t these ways for people who aren’t Jewish to connect with this community, and in that absence, it’s a loss for these communities to not have that.”

Reid now lives in Pittsburgh. He says once he completes the two Ohio Jewish community histories he’s writing, he’ll work on filling in gaps on small Jewish communities in western Pennsylvania.

When asked if he has plans to compile his Ohio histories into a book, he says, “Perhaps someday I’ll try to tie together all the pieces. It will be a project for down the road.”

Eleven of Austin Reid’s local Ohio Jewish histories are posted at columbusjewishhistory.org/research/central-ohio-histories.

To read the complete February 2023 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.