The Jews of Easy Company

By Jim Nathanson

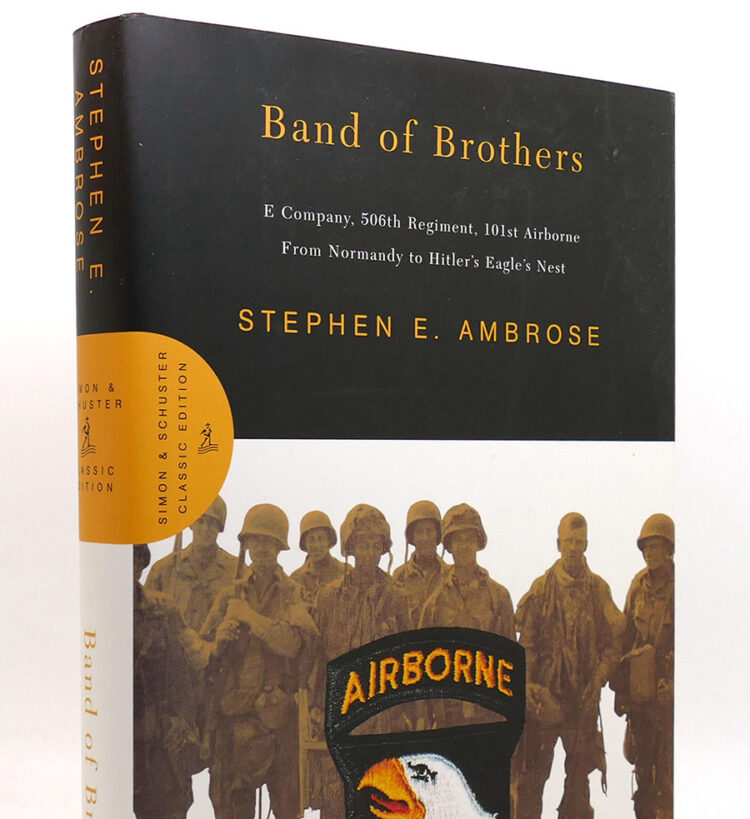

Ed Shames died Dec. 3. He was 99 years old, the last surviving officer of Easy Company, the World War II combat unit (E Company, 2nd Battalion, 506th Regiment, 101st Airborne Division) made famous by Stephen Ambrose’s 1992 book Band of Brothers and the 2001 HBO miniseries of the same name.

Shames jumped behind enemy lines with the 101st on D-Day, receiving the regiment’s first battlefield commission a week later. His company commander also recommended him for the army’s Distinguished Service Cross for bravery under fire.

He fought in all of the 101st major engagements, including a second combat jump during the ill-fated Market Garden campaign where he served as a frontline intelligence officer, making at least one foray behind enemy lines in civilian clothing, before taking command of Easy Company’s 3rd Platoon in October 1944. Shames volunteered for Operation Pegasus, a daring mission that rescued 138 allied soldiers trapped behind enemy lines, and was part of the defense of Bastogne during the bitter monthlong Battle of the Bulge.

Shames was with Easy Company when it took Hitler’s fabled mountain retreat, Eagle’s Nest, and he was one of the first members of the 101st to enter Dachau shortly after it was liberated. At war’s end, his combat record earned him a bronze star.

Based on his performance as an intelligence officer and a combat leader, he was recruited by one of our nation’s intelligence services, where he worked for the next 30 years.

Ed Shames was Jewish — a practicing Jew. According to his obituary in the Norfolk Virginian-Pilot, “He served cognac he had liberated from Eagle’s Nest at his son’s Bar Mitzvah. The bottle was labeled ‘for the Führer’s use only!’”

However, one would never realize Shames was Jewish by reading Ambrose’s book. He is referenced a number of times but his religious affiliation goes unnoted.

This omission becomes significant only because of the way Ambrose treats other Easy Company Jews.

The villain of the story, the most hated officer in Easy Company, was a Jew, Capt. Herbert Sobel, the man who led Easy Company throughout its stateside training.

Here is how Ambrose describes him:

“(He was) fairly tall, slim in build…His eyes were slits, his nose large and hooked…He had been a clothing salesman and knew nothing of the out-of-doors. He was ungainly, uncoordinated, in no way athletic. Every man in the company was in better physical condition. His mannerisms were ‘funny,’ he ‘talked different.’ He exuded arrogance. Behind his back, men cursed him, ‘f…ing Jew’ being the most common epithet.”

He was criticized most for his harsh training methods. But what goes unnoticed by Ambrose is that Sobel truly led the men throughout their training. If they went on a brutal hike without sleep, Sobel led them. If they were forced to run with full packs up and down the infamous Mt. Currahee located near their primary training base, Sobel led them. Only well after the war did some of the men acknowledge that Sobel had made Easy Company. They were the tough, well-trained outfit they were largely because of Capt. Herbert Sobel.

The fact that they hated him is no surprise; he was uncompromisingly tough on them and, yes, probably more than a bit of a jerk. Soldiers almost always hate their drill instructors. That they were antisemitic in their attacks on him is also not surprising; after all, most were rural or small-town gentiles. Sobel could well have been the first Jew most of them had ever known. One can forgive the men of Easy Company for how they reacted to Sobel. What one needs to ask is why Ambrose, in writing Easy’s story, didn’t make those connections.

After all, Sobel had earned his paratroop wings just as they had. While he lost command of Easy Company, he did jump with the 101st in the early morning hours of June 6 and fought in many of the same battles as did Easy Company, earning, like Shames, a bronze star in the process. After the war he entered the reserves, was called up during the Korean conflict, and retired with the rank of lieutenant colonel.

Ambrose even casts a horrible tragedy in Sobel’s life in the worst possible light. In 1970, he tried to kill himself with a pistol shot to his head. Ambrose writes he “bungled” his own suicide. The bullet entered his temple, severed both optic nerves and exited through the opposite side of his head. Somehow, he survived. An unsuccessful attempt, yes, but a “bungled” attempt — well, that leaves a whole different impression.

The only other Jew noted by Ambrose was a private named Joseph Liebgott. A good soldier, he was said to be one of the funniest guys in Easy, except when it came to financial matters. Sound familiar?

And, as reported by Ambrose, Liebgott was one of the very few Jews in Easy Company — no mention of Ed Shames.

Actually, unknown to Ambrose, Liebgott wasn’t even Jewish. He was a Catholic though his mother may have been Jewish. Ambrose may have also erred in his description of Sobel’s physical abilities. He writes that Sobel could barely complete 30 pushups with “arms trembling,” yet his son reports that his dad regularly did 50 or more pushups every evening with little or no effort.

Ambrose also claims, as quoted above, that Sobel was in no way athletic, yet his son points out he was on his high school’s swim team where he did quite well.

While Ambrose’s writing is blind to its antisemitic elements, I think there is a broader issue at play here.

In many ways, how Ambrose and the men of Easy Company thought of Sobel simply fits the stereotype of the weak Jew that so many, Jews included, cling to even today. He was “unathletic,” “physically weak,” and “uncoordinated,” In a phrase, not fit to be a combat officer. Ed Shames, fitting less the stereotype, his Jewishness goes unnoticed.

Over the last few years, I’ve given talks at Beth Abraham Synagogue that focused on Jewish physicality.

The first, Mobsters and Athletes, discussed an unbelievable outburst of Jewish physicality on both sides of the law during the first half of the 20th century, especially in the years between the two world wars. The emergence, if you will, of tough Jews.

The second talk tried to explain why Jewish physicality comes as such a surprise to both Jew and non-Jew alike. I traced it back to the earliest years of rabbinic Judaism and the reaction of the rabbis to the horrific losses suffered in the Bar Kokhba revolt of 132-136 C.E. Fearing that further armed resistance to outside rule could lead to the destruction of the Jewish people, they set out quite deliberately to “defang” what it meant to be Jewish — a process accelerated by the emergence of rabid antisemitism in Europe and the Arab world in the centuries that followed.

The consequence of early rabbinic intention and antisemitism was a Judaism that was inward looking and rejected much of the secular world and a Jewish culture that valued learning over physicality. This view is succinctly summed up in the advice Rabbi Yitchak Rasofsky of Chicago gave his son, Beryl Rasofsky in the early 1920s: Jews do not resort to violence, he said, “let the (goyim) be the fighters…we are the scholars.”

Beryl Rasofsky, by the way, didn’t listen to his father’s advice. Also known by the name Barney Ross, he became one of the best fighters of his era, holding three different world titles during the 1930s — Light Weight, Light Welterweight, and Welterweight — and going 74-4 and 3 in 81 bouts, winning 22 by knockouts.

The prevalence of the stereotype not only leads to tough Jews going unnoted but often leads to those noted being recast to fit the stereotype.

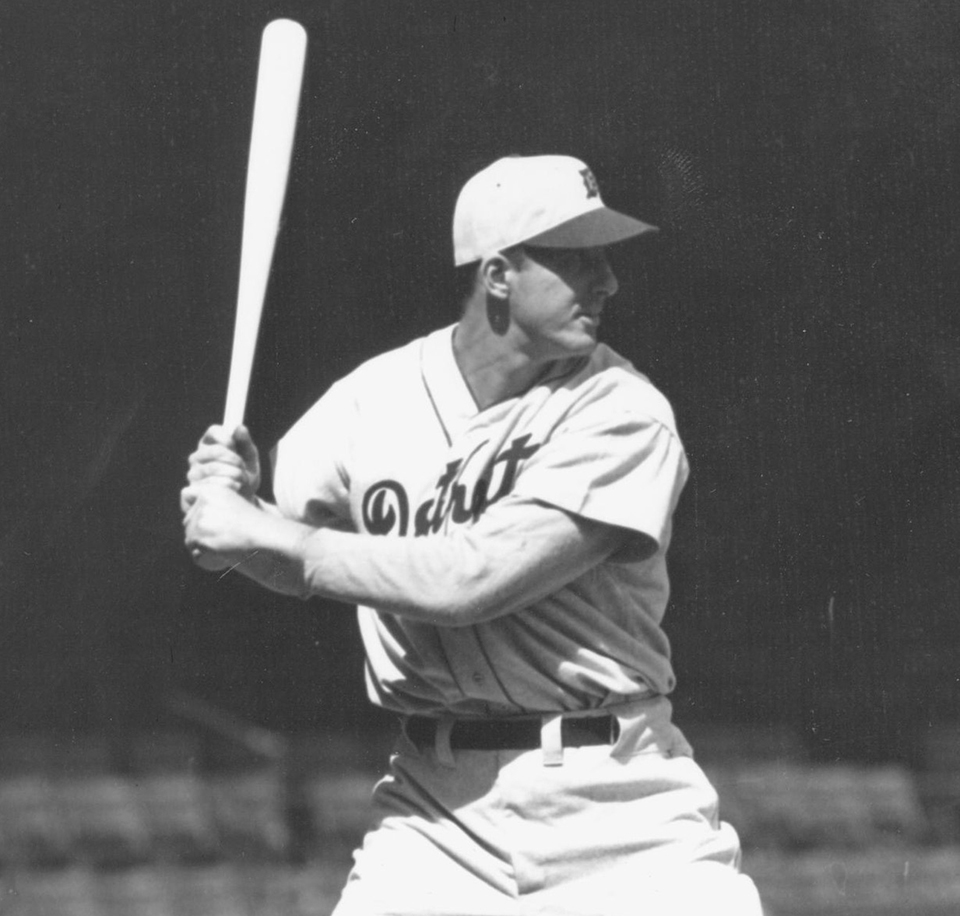

The great ballplayer Hank Greenberg, one of the best hitters of all time, was often criticized for his awkwardness, especially as a first baseman, the position he played for nine of his 13 seasons in the major leagues. He isn’t the first power hitter to be less than stellar as a fielder, but the frequent references to his lack of physical coordination went, I think, beyond what was justified.

His “fielding percentage,” for example, the most common baseball statistic for measuring defensive skills, shows he was actually quite competent at first base. Except for his rookie season in 1933 and the 1936 season, he finished among the top five of all American League first basemen, even having the best fielding percentage at that position in 1939.

Meyer Lansky, the best-known Jewish gangster, is often thought of as the mob’s brains or accountant. Rarely is he described as the tough SOB that he was. The Italian mobster Lucky Luciano recounted that he and Lansky first met as teenagers when Luciano and some other punks surrounded the much younger Lansky as he was walking alone. Luciano threatened Lansky: “If you wanna keep alive, Jew boy, you gotta pay us (protection).” Lansky just looked the much-bigger Luciano in the eye and said, “go f… yourself,” his fists clenched ready to fight. They became fast friends and, together would control the mob for most of the ‘30s and ‘40s.

Ed Shames was one tough Jew. It’s a shame Ambrose did not acknowledge it. And, for that matter, acknowledge that in many ways, so was Herbert Sobel.

Jim Nathanson, a local, state, and national political and public affairs consultant, has given numerous talks on political and historical topics at Dayton’s Beth Abraham Synagogue.

To read the complete February 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.