Biography of Dayton congressman explores politics of race, religion in Civil War era

By Martin Gottlieb

Clement Vallandigham — the most prominent Daytonian of the 19th century by far — was pro-slavery. Indeed, he denied that slavery raised any moral issue. He said this country was for White people, and the interests of Black people should not be considered.

However, in researching my recently published book about him, I came across some intriguing material about his views on Jews.

Vallandigham argued for Jewish rights. He did so with unusual vigor. Why? What explains his combination of intolerance and enlightenment? Why did a man incapable of seeing the harm of prejudice toward one minority become a force against prejudice against another, Jews?

First, a note on his prominence: Vallandigham’s name was a household word. He — not the Wright brothers — put Dayton on the map. He was known for much, but first for being Abraham Lincoln’s leading antagonist in the North. He was the most prominent person among the “Copperheads” or Peace Democrats. That group was against war with the South. Vallandigham insisted that if the Republicans simply gave up their opposition to the extension of slavery, the problem between North and South would go away.

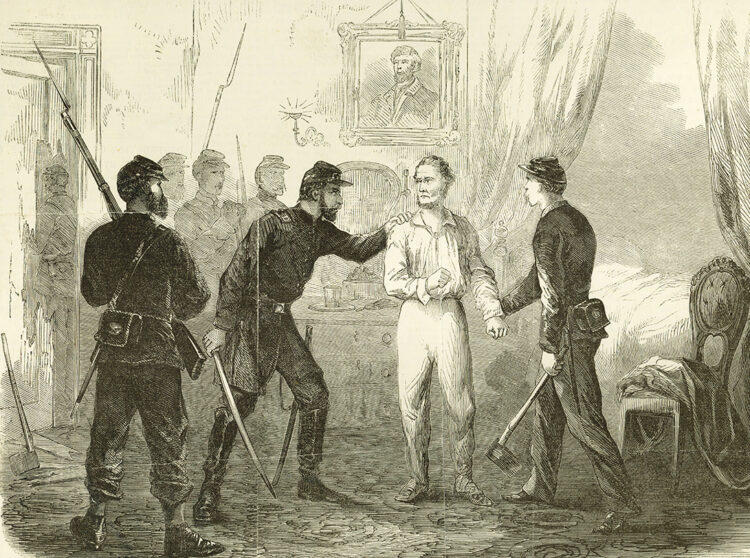

Vallandigham was thrown out of the country by Lincoln for his views (the central story in my book). Then he was nominated by the Democrats for governor in 1863. He ran the race from exile in Canada. The election generated higher voter turnout than presidential elections in Ohio, over 80 percent. If he had won, that would have been a turning point in the war. And Vallandigham would have become the presidential candidate of the Democratic Party’s base. If he had been elected, re-unification almost certainly would not have happened.

If you hear Vallandigham’s name around town these days or see it at certain places online, you might get the impression he was not pro-slavery, but merely pro-state rights. This is wrong. He explicitly, adamantly embraced Southern slavery as a positive good in an 1863 congressional speech. He had held a state rights position earlier, but the war years are the ones that count in his story. They were his hour upon the stage.

Jewish concerns: When an issue arose in Europe about whether Jewish American travelers would be granted the same rights as other American citizens, Vallandigham introduced a resolution in the House, insisting that they must be.

But the main Jewish issue in which he played a role was whether rabbis could be chaplains in the Civil War. Early in the war, a sort of omnibus war bill was enacted; one small provision said that chaplains could be drawn from qualified clergy in any Christian denomination.

Vallandigham took offense. He did so on the floor of the House, which was where he often stationed himself in the task of giving the Republicans fits. He was the only member of the House to complain about the provision. According to historian Bertram Korn, “He denounced the underlying implication of the bill that the United States is a Christian country, in the political sense, and branded the law as entirely unjust and completely without ‘constitutional warrant.’”

Vallandigham said, “There is a large body of men in this country, and one growing continually, of the Hebrew faith, whose rabbis and priests are men of great learning and piety, and whose adherents are as good citizens and as true patriots as any in this country.”

The Republicans running the House ignored him — which they seemed to do as a matter of policy — and passed the bill.

After that, Jewish leaders objected, taking their case to Lincoln. He said it had been an oversight — which is really not at all clear — and that it would be remedied. It was, though that took a year.

Why had Vallandigham spoken up when nobody else had, aside from the joy he took in vexing Republicans? One factor surely is that there were Jews in Dayton. Vallandigham would certainly have known local Jewish leaders. He might have attended a sermon or two. As the son and brother of a minister, he was deeply interested in religion. He would also have been interested in Jewish votes, not because there were many of them, but because his election margins were always paper thin.

Jews were not a voting bloc committed to one party or the other. Some in the North were motivated by anti-slavery views and were Republicans. But there was another force drawing Jews to the Democrats: controversy over immigration issues.

In 1850, the country had about 50,000 Jews. A decade later, the figure was about 150,000, or half of one percent of the nation. They were scattered in both North and South.

The country had seen a massive immigration wave — overwhelmingly Christian — in the early 1850s, resulting from two factors: the Irish potato famine and the failure of some liberal revolutions in Europe. After those failures, many people felt the need to get out of Europe. Jews were among them.

The wave was so big that immigration temporarily eclipsed slavery as a political issue. An anti-immigrant party — known as the American Party or the “No Nothings” — was born and prospered briefly. That party was anti-Catholic, because the Irish immigrants and many others were Catholic. The party was not particularly antisemitic. In fact, antisemitism didn’t surface as much of American issue until the war, when the need for scapegoats — North and South — fostered it. After the war, it receded, until the great wave of Eastern European Jewish immigration starting in the 1880s.

Still, in the 1850s, some Jews saw in the anti-immigrant movement a threat to Jews. If Jews weren’t in the target zone of the ethno-centrists yet, that didn’t mean they never would be.

When the anti-immigrant party faded — as the immigration wave faded and slavery came to dominate political discourse — most of its adherents seemed to turn to the Republicans.

The Democrats weren’t an option; they were organizing the Irish immigrants in places like New York. The Republican anti-immigrant forces certainly didn’t represent the views of Lincoln. But some Jews never forgot anti-immigrant forces were there, in the Republican Party.

This seems to have been true of the famous Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise of Cincinnati, the Reform leader. He was a passionately partisan Democrat, seeing the Republicans as a menace. When Massachusetts — the hotbed of anti-slavery sentiment — passed a law in 1859 imposing new restrictions on immigrants, he saw that as a statement about who the Republicans really were.

Well, if you see the Republicans as the anti-immigrant party, you begin to see why it would make sense for Vallandigham to reach out to Jews. He liked the idea of immigrants identifying with the Democrats. Counter-intuitive as this seems today to people who know Vallandigham as a racist, he saw the Democratic Party as the one committed to what we today call diversity. It was the party that had stood up to the No-Nothings and did not now house them.

But including Black people in the Democrats’ coalition wouldn’t have been politically useful, because there were few Black people in the North and most couldn’t vote. Also, the Democratic politicians enticed Irish immigrants into the party by portraying the Republicans as the party of Black Americans, who would compete with the Irish for jobs if freed.

There were multiple reasons for Vallandigham’s views on race, including that he had come of age in the Democratic Party, which could only maintain its national coalition by tolerating slavery. He came up with rationalizations for his views, insisting, for example, that Black people were a “cursed” race, “a servile and degraded race almost from the beginning of time.”

Of course, some who hate Jews go back to biblical times in pursuit of a rationalization for their views. One can imagine Vallandigham doing that if he had a political motive. Maybe he truly held the views he publicly espoused about Jews and Black people. But another possibility is simply that denouncing Jews would not have suited his political purposes.

Retired Dayton Daily News editorial writer Martin Gottlieb is the author of Lincoln’s Northern Nemesis: The War Opposition and Exile of Ohio’s Clement Vallandigham (McFarland & Co.) He is also the advisor to The Dayton Jewish Observer.

To read the complete December 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.