Not-so-random acts of kindness

The Power of Stories. A Series

Jewish Family Education

By Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Assisting with the Albanian Muslim refugees in the late 1990s, Israel’s field medical team in Kosovo noted that the adult-focused aid agencies were overlooking the traumatized children. In response to its request for volunteers, virtually every secular and religious youth group in Israel sent teams of youth leaders who organized all manner of camp-style activities — from sports to the arts — to make the children’s temporary exile feel like a vacation. The late Rabbi Jonathan Sacks concluded that it demonstrated the beauty and healing power of kindness.

Kindness is fundamental to a healthy society. Psychological research has identified kindness as a universal character strength and virtue, observed its contagious nature, and cataloged its significant physical and mental health benefits. One of the most intriguing discoveries is how kindness generates an increase in oxytocin, the brain hormone responsible for the sense of connectedness and trust. “It’s what helps societies bond (and keeps) groups of people together,” explains psychiatrist Dr. Marcie Hall.

Long before the advent of modern psychology, kindness — chesed or gemilut chasadim — as a virtue, an action, and a kind of social cement, was a central pillar of Judaism.

The Torah is bookended by acts of lovingkindness: God clothes Adam and Eve and buries Moses. In the Book of Exodus, chesed — God’s kindness and love toward humanity — is listed as one of the 10 Divine attributes, which the Talmud explains are prototypes for how humans should act in relationship to one another.

“So powerful is gemilut chasadim,” writes Rabbi Jeffery Salkin, “that performing acts of lovingkindness is the closest that humans can come to a genuine imitation of God.”

Appearing in the Torah nearly 200 times, chesed is often considered Judaism’s most comprehensive and fundamental of all ethical virtues.

This significance is captured by a well-known aphorism: “The world stands on three things: Torah, avodah (service to God), and gemilut chasadim (acts of lovingkindness).”

Despite their importance, however, the concepts of chesed and gemilut chasadim are not easily explained. Chesed expresses both emotion and action, caring and compassion through giving of oneself, the moral commitment we have to one another, simply because we are human.

Gemilut chasadim emphasizes the underlying notion that chesed isn’t generally accomplished by momentary random acts of kindness, but, as Rabbi Sacks explained, by becoming engaged with real people as we give of our time, caring, and resources.

“It’s about how people live together despite their differences…about working together for the sake of the common good.”

And, Rabbi Paasche-Orlow points out, it’s when the command to “love your neighbor as yourself is truly fulfilled.”

Here are some Jewish tales that illustrate the notions of chesed and gemilut chasadim.

Yiddish folklore tells of the Rebbe of Nemirov, who would vanish early every Friday morning. His devoted followers concluded he must ascend to Heaven to plead on behalf of the community. A visiting Litvak, confident in his superior rational worldview, resolved to discover the real answer. One Friday, he secretly followed the Rebbe who, dressed as peasant, went into the forest.

There, he chopped down a tree and split the logs into firewood which he carried in a bundle back to town. As the Litvak watched, the Rebbe knocked at the run-down-cottage of a poor widow, announcing he had kindling for sale. Assuring her she could pay on credit — after all, doesn’t God always provide? — he entered, stacked the firewood by the hearth, and lit a fire. Then the Rebbe returned home. From that time on, whenever the townspeople said their Rebbe ascended to Heaven, the Litvak—who became the Rebbe’s student—responded, “And maybe even higher.”

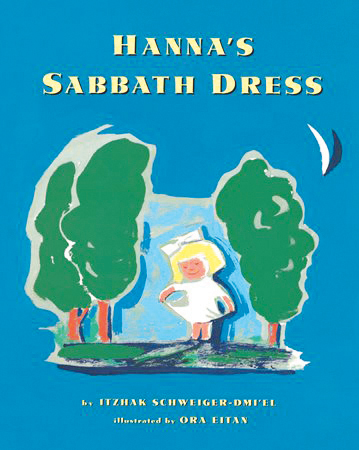

A popular folk tale from pre-state Israel tells the story of Hannale, who receives a new white Shabbat dress. Cautioned by her mother not to get dirty, the delighted Hannale heads outdoors and proudly shows the dress to her dog, Zoozie, and a nearby cow, Edna, carefully keeping it out of their reach. Hannale then sees an old man with a heavy sack trudging out of the nearby woods. After showing him the dress, she asks about his sack, which he explains is filled with coal.

She offers to help him carry it, and they walk together for a ways. Returning home, she discovers her dress is marred by black stains and bursts into tears. The early-rising moon looks down and whispers, “Are you sorry you helped the old man?” When Hannale replies no, she is just sad about the stains, the moon reassures her that all will be well. Shimmering moonbeams flow from the sky, turning the stains into spots of silvery light, making Hannale’s dress more beautiful than ever.

There are 613 Torah commandments, the most central obligation of which is acting with lovingkindness, as noted by Rabbi Akiva: “This is a great principle of the Torah: You shall love your neighbor as yourself.”

Fundamental to living a meaningful Jewish life and creating a good, cohesive society, gemilut chasadim should be our mind-set and lifestyle, guiding how we interact with family and friends, fellow citizens, and strangers, even when it is hard, writes civility author Stephen Carter. It would go a long way toward healing today’s fractured world.

Literature to share

Be a Mensch: Unleash Your Power To Be Kind and Help Others by Elisa Udaskin. Being a mensch doesn’t require superpowers — just “simple shifts in your approach to everyday interactions.” Filled with real-world anecdotes and excellent insights, this slim book offers practical ideas for adults and kids about kindness and helping others through difficult situations from life’s tragedies to daily interactions: including when someone doesn’t meet our expectations. Be a Mensch is not only fun to read, it’s an eye-opener to many unexpected ways of being a good and kind person.

Pink and Say by Patricia Palacco. Two Union soldiers, one White and one Black, meet on the battlefield. Their true story involves a rescue from the battlefields, a relationship built on common humanity, and the devastation wrought when people cannot see the image of God in one another. While written as an illustrated book for elementary ages, it is a powerful story of lovingkindness for adults as well, especially relevant in today’s fractured society.

Hanna’s Sabbath Dress by Itzhak Schweiger-Dmi’el. An excellent YouTube video recording of this classic tale, also a PJ Library book, retold in a lovely British accent, available at Storytime with Raquel.

To read the complete November 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.