A heritage of forgiveness

Our Dual Heritage Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

When writer and storyteller Sarah Montana was 22, her mother and brother were shot to death in their home by a neighborhood teen looking for valuables to steal.

Seven years later, she recounted in a TED talk, “I realized…we were still connected. That steel tether of trauma that he hooked into my side…was still there… And it was with a little horror that I realized that he may have killed them, but I chose to keep us connected… I realized the only way to get rid of this dude was to forgive him…”

At the foundation of Western culture’s embrace of forgiveness is the Bible. Humans are imperfect, exert free will, and inevitably make mistakes, disrupting relationships with others, with oneself, and with God.

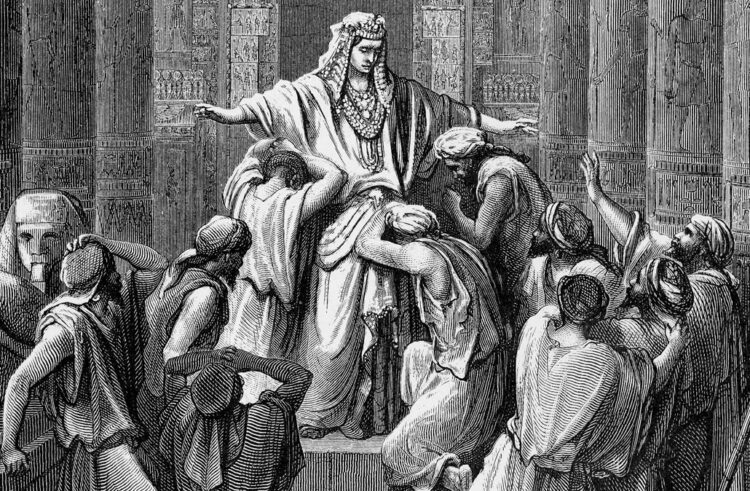

Forgiveness is the antidote. The clearest biblical example is Jacob who, favoring Joseph over his brothers, kindles enmity among them to the point where the brothers plot his murder, ultimately selling Joseph into slavery. Yet in the end, Joseph forgives his brothers and reunites his family.

This is a first in history according to classicist David Konstan. He argues that the ancient cultures had no concept of forgiveness in a moral sense, that is, admission of guilt by the offender, remorse, and repentance.

Instead there was appeasement: the perpetrator might rationalize the transgression, make excuses, beg, plead, even “perform some ritual of abasement or humiliation,” as if to say to the victim, “I am not really a threat.”

The victim, in turn, no longer needs to take revenge; proper respect has been shown, and the victim’s dignity or honor has been restored.

Jacob’s reunion with Esau is a case in point: Jacob repeatedly refers to himself as “thy servant Jacob” and addresses Esau as “my lord,” sends gifts, and bows low to his brother a full seven times.

Biblical forgiveness isn’t only expressed through story; it’s also a Divine command: “You shall not hate your brother in your heart,” nor should you take revenge or bear a grudge (Lev. 19:17-18).

Furthermore, Jews are commanded to observe a full day each year for atonement and forgiveness (Lev. 23:26-28).

Above all, just as God forgives us, so should we, created in God’s image, aspire to forgive: “Who is a God like You, forgiving iniquity and remitting transgression; Who has not maintained His wrath forever…(Micah 7:18).”

Parallel themes are found in the Christian Bible, in the parable of the Prodigal Son, Jesus’ teachings about forgiveness as an obligation, and Paul’s linking of forgiveness to imitatio Dei (imitation of God).

With its roots in the Bible, it’s no wonder American culture — from the time of the early settlers until the modern era — has embraced the notion of forgiveness.

But religion isn’t the only domain of forgiveness. Science offers some startling insights. Brain research observes that forgiveness triggers a region in the limbic system, the emotion center of the brain, similar to that activated by empathy.

This finding can be explained by their shared link to human relationships and capacity for “expanding our perspectives about ourselves, others, and life,” explains author Emily Hooks.

Their common purpose is to foster human connection. Numerous psychological studies have also demonstrated that positive feelings toward perpetrators initiated by receiving sincere apologies or restitution for offenses also increase the likelihood of forgiveness by the victim.

Apparently humans are hard-wired with the ability to foster and protect human connection.

The benefits of forgiveness to physical, mental, emotional, and spiritual health are also well-documented. Decades of studies have observed a causal relationship between forgiveness and blood pressure, heart rate, and stress hormones.

Forgiving others reduces feelings of restlessness, anxiety, depression, anger, hurt, and hostility, while it increases hopefulness, contentment, and spiritual fulfillment.

And a review of scientific literature suggests unforgivingness may compromise the immune system, impeding the production of critical hormones and disrupting the cellular response to infection.

Beyond religious precepts and health benefits, why forgive? It can’t heal you. It doesn’t undo the wrong. It won’t make you a good person.

Sarah Montana concludes, “Forgiveness is designed to set you free.” Free to reject the wrong done — “What you did was not OK!” — while acknowledging the wrongdoer as an imperfect fellow human. Free to drop the burden of hurt. Free to reframe, rebuild, or return to the relationship. Free to move forward.

While forgiveness was once well-rooted in American culture, today it is deteriorating, evident within families, in cities, in the daily news, and on social media, with no end in sight.

Perhaps we could learn something about forgiveness from Eva Mozes Kor. At the age of 10, she and her sister were subject to a year of gruesome twin experiments by the infamous Auschwitz physician, Dr. Josef Mengele.

Decades after liberation, Kor interviewed a colleague of Mengele, Dr. Hans Münch, who admitted “he lived with the nightmare every single day of his life” and agreed to sign a document of testimony.

Kor recalled, “I tried to think of a way to thank Dr. Münch. Then, one day, I thought, ‘How about a letter of forgiveness?’…I realized that I had the power to forgive. No one could give me this power and no one could take it away.”

Although her many acts of forgiveness of the Nazis have been criticized, she points out that both victims and victimizers suffer from wronging and evil, and the added tragedy is how this legacy is passed on to their children.

“How can we build a healthy, peaceful world while all these painful legacies are festering underneath the surface?” Kor asks. “I see a world where leaders will advocate and support with legislation the act of forgiveness amnesty and reconciliation rather than justice and vindictiveness.”

Kor’s message echoes the words of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr., the voice of another persecuted people: “We are to go out with the spirit of forgiveness, heal the hurts, right the wrongs, and change society with forgiveness.” Theirs are the voices of true wisdom.

Literature to share

On a Clear April Morning: A Jewish Journey by Marcos Iolovitch, translated by Merrie Blocker. A fascinating, inspiring autobiographical novel, On a Clear April Morning traces the harrowing journey of Marcos Iolovitch from czarist Russia to Brazil, where his family hopes to become farmers. As he recounts scenes of unimaginable poverty, humor, tragedy, and love, Iolovitch emerges as a go-getter who takes advantage of unexpected opportunities and eventually becomes a noted poet, essayist, and crusader for social change.

A Ceiling Made of Eggshells by Gail Carson Levine. Set in 15th-century Spain during the era of King Ferdinand and Queen Isabella, this historical novel is narrated by the inquisitive and adventurous Loma, who lives in a Juderia (Jewish quarter) and dreams of a family of her own. As pressures from the Inquisition increase, Loma’s stern but beloved grandfather chooses her to accompany him on his travels to visit the monarchs and other Jewish communities in a desperate quest to protect Spanish Jewry. Well-researched, this novel for middle grades paints a realistic picture of the historical era while offering an engaging read.

To read the complete August 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.