Empathetic imagination during the pandemic

Until we have a better solution, social distancing is the only option we have.

A Bisel Kisel with Masha Kisel, The Dayton Jewish Observer

One of the strangest things about living through this pandemic is that those who shelter at home and those on the front lines occupy two different realities.

For some it feels like time has slowed down to a crawl, while others rush at breakneck speed to outpace the pandemic’s devastation.

For the good of all, we need to bridge the distance between these experiences. During this time, an exercise in empathetic imagination is just as important as government-issued mandates to stay at home.

It’s human nature to shut out everything beyond the bubble of our personal circumstances during a time of fear and uncertainty, and it’s easy to be lulled into a delusion that the danger isn’t real if we don’t personally see it or feel it.

As infectious disease specialist Dr. Emily Landon from University of Chicago has put it, “A successful shelter-in-place means you’re going to feel like it was all for nothing, and you’d be right: Because nothing means that nothing happened to your family. And that’s what we’re going for here.”

But at a time when every human fate depends on actions of the collective, I see a rupture in understanding the importance of social distancing.

Every day I see examples of reckless behavior around my neighborhood: people chat clustered on the street corner, shake hands, groups of high school students run in tight formations. With utter disregard for human life, some religious congregations are still holding services.

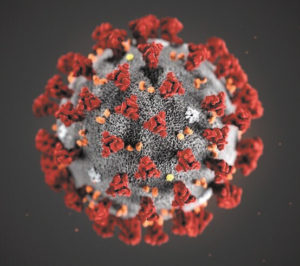

The invisibility of the novel coronavirus makes the pandemic feel prosaic. For many, days are dulled by genteel boredom.

Hours are filled with homeschooling, Netflix, baking projects, and walks around the block as we wish each other to “hang in there!” from 6 feet away.

We try to spice up the blandness of this existence. I pour extra hot sauce on my breakfast eggs. I feel an urge to take a risk.

What if I were to burst into song and dance during my Zoom lecture for English 100? What if it goes viral? I imagine the humiliating zing of internet embarrassment. How would that feel?

And what if on my daily walk, I press the button at the stop light with my finger instead of my elbow and then touch my face? I pinch the skin on my wrist to prevent myself from doing something stupid. The small pain is an event.

My self-destructive thoughts try to break me out of my still-life cocoon. Maybe all of us stay-at-homes will discover some latent masochistic tendencies in quarantine?

Locked in place, I travel through time. I could be living out my sunset years, I could be 5 and lost in play or I could be 16, daydreaming to Sonic Youth’s Goo blasting on my headphones.

Some days, a gauzy serenity wraps around our homelife. In those moments, when my kids are quietly immersed in books, I am filled with gratitude for this wrinkle in time. But I know that this peaceful pause is a mirage of privilege.

For those on the front lines of the pandemic, especially healthcare professionals in hotspots, time is a killing machine.

Doctors and nurses spend their days in fevered calculations. How many hospital beds are left? How many ventilators? How many people have I touched today? How many days before I get sick too?

Behind protective gear, like astronauts on a spacewalk, their lives are tethered to chance.

The essential workers forced into heroism in hospitals, pharmacies, and grocery stores did not sign up for this level of risk.

Their safety depends on reducing the number of infected patients, infected customers. It may not feel like it, but our split-screen realities are an interconnected system that can preserve life or cause more death.

Imagine seeing the fear in your patient’s eyes, hearing them beg to see their loved ones before they die, watching them deteriorate. You are unable to help. You know you or your loved one might be next.

Those of us who feel far away from this horror all play a role in perpetuating the tragedy or helping to stop it.

We know now that this disease is primarily spread by asymptomatics. You might be a carrier and not even know it. We may not all be essential workers, but we are all essential in slowing the pandemic’s spread even as it gets progressively harder to stay at home.

Sure, there are compelling reasons to “reopen” the country and allow people to go back to work. Landon’s statement that “nothing will have happened to your family” ignores the millions who have lost their sources of income.

My own job as a university professor is uncertain if students don’t come back to campus in the fall. But the truth is that unemployment is temporary, and loss of life is irreversible.

We need to stay the course because, currently, there is no alternative. The United States did not act quickly enough to halt the spread of this deadly disease and until we have a better solution, social distancing is the only option we have.

Ohio is lucky to have a governor with foresight. DeWine’s early shelter-in-place order has already saved many lives; I hope and pray that local governments continue to reason wisely and ignore the president’s foolish insistence to end social distancing measures too early, condemning hundreds of thousands to death.

A stimulus plan focused on helping workers and providing universal healthcare would make this closure tolerable for the most financially vulnerable among us.

Unfortunately, right now we cannot rely on the federal government to protect us from the pandemic or from economic devastation.

Here in the Miami Valley, many families will need help putting food on the table. Our empathetic imagination must extend also to those who live without a paycheck or savings.

Some politicians might claim that they are acting compassionately by calling to reopen the economy, but telling people that they will avoid destitution by risking deadly infection is a horror film trade-off.

Our country has enough money to help its citizens safely weather the pandemic.

But until we can elect leaders with an empathetic imagination, we must become those leaders ourselves and do what we can, whenever we can, to get through this difficult time together.

Masha Kisel is a lecturer in English at the University of Dayton.

To read the complete May 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.