A heritage of wandering

Our Dual Heritage Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

It took more than 300 boxes, three sets of movers, and two weeks to move just over a mile to our new home. Who knew we had so much stuff, even after we’d eliminated all the “don’t need or haven’t used in three years” items?

Why do people move? According to a U.S. Census Bureau study, over three quarters of Americans move for housing- or family-related reasons, with job-related reasons a distant third. Just two percent move for other reasons. While these general categories have likely been stable throughout history, I suspect the statistics themselves don’t reflect the full story of movement in Jewish and American traditions.

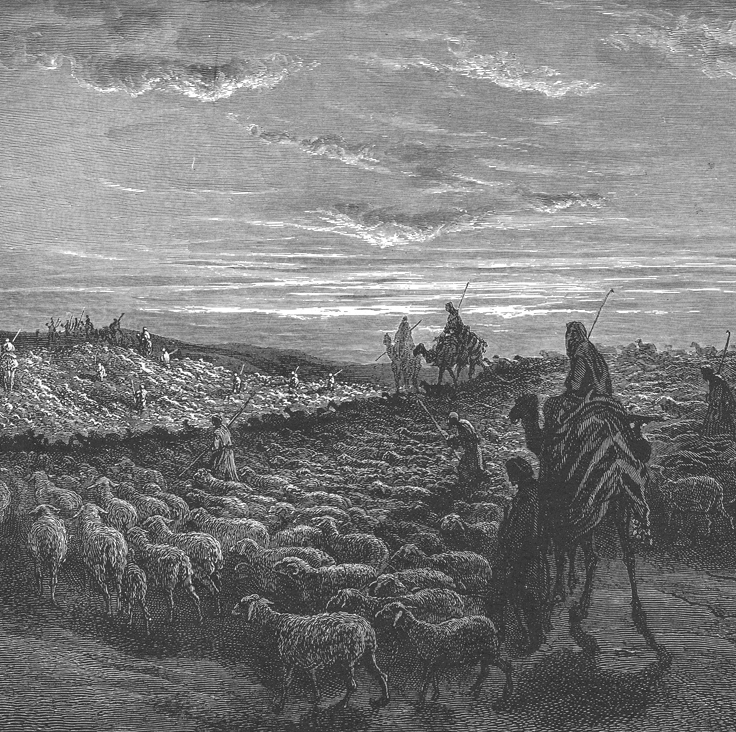

The story of Jewish wandering begins with Abraham. “The Lord said to Abram: “Go forth from your land, and from your kindred, and from your father’s house, to the land that I will show you.”

From Mesopotamia to Canaan to Egypt, back and forth, the Bible’s patriarchs and matriarchs moved with all they acquired, seeking a place to settle secure from famine and warring neighbors.

For a time they found their home in Egypt, having relocated there in the time of Joseph. However, the Israelites eventually became enslaved to a pharaoh “who knew not Joseph,” necessitating the addition of “secure from enslavement” to the home they sought.

Following the Exodus, when they again took everything with them including riches from the Egyptians, the Israelites wandered for 40 years before arriving and settling in Canaan.

“Much of the Torah is focused around the search for home,” Rabbi Elliot Kukla writes, echoing the Census Bureau conclusions. But it wasn’t just about housing or family or even a job. The Exodus — in fact, the entire Israelite saga — was a divine journey initiated by a covenant and a promised inheritance, involving nearly an entire population and not just a statistical “two percent.”

Jewish wandering continued. The exile of nearly the entire Jewish population to Babylonia and the return of a remnant to Jerusalem. A further dispersion of Jews under Roman and Byzantine rule into the lands of the Mediterranean and Europe. The Spanish Inquisition and expulsion. Jewish settlement in the Americas and, with the rise of Zionism in the late 1800s, a mass return of Jews to the land of Israel.

Over time, Jews have wandered across the globe, settling in lands as diverse as India, Ethiopia and the Caucasus (eighth century B.C.E.), Russia and China (seventh century), and Scandinavia (15th century).

Such movement has been the result of many different influences: force, opportunity, antisemitism, a desire for adventure, the search for a new life or job, the reuniting of family, and — in the case of Israel — a love for the country.

The story of American wandering parallels that of ancient Israel, beginning with the Pilgrims.

“Like the Israelites’ exodus from Egypt, the Pilgrims had left what they saw as an oppressive, degraded situation in Europe, in which they could not worship freely, in order to create a new life in America,” writes Angela Kamrath, author of The Miracle of America. “They were God’s people, and America was their Promised Land.“

Theirs was a divine journey whose purpose was to establish, in the words of John Winthrop, founder of the Massachusetts Bay Colony, “a City upon a Hill,” a virtuous and successful example to other nations.

Journalist John O’Sullivan emphasized it would be a journey whose founding principle was freedom. And journey they did. Seeking freedom and opportunity, newcomers from lands across the globe arrived on America’s shores, and like the biblical Abraham in Canaan, wandered its vast plains, traversed its great rivers, and settled in its valleys.

Like ancient Israel, America still pursues the dream of building a virtuous society founded in freedom, two pursuits that continue to bring “the huddled masses to our teeming shore.”

Americans are still on the move across the country, even outward into space and inward into the genome. But today’s journeys seem to be missing the divine spark, the sense that we’re pursuing something greater than just a series of disconnected individual successes.

What is our divine journey as an American people? What are we doing about building a City upon a Hill?

Perhaps we should follow the advice of the prophet Jeremiah to the Jews exiled in Babylon. He encouraged them to “build houses and live in them, plant gardens and eat their fruit, take wives and have sons and daughters…and seek the welfare of the city where I have sent you into exile, for in its welfare you will find your welfare.”

The divine spark is ignited when we not only do good for ourselves, but when we also pursue virtue by doing good for others, whether neighbors, communities, or an entire country.

After all, God didn’t only promise blessings for Abraham. “Through your offspring (who exemplify goodness and virtue) all nations (into which they wander) will be blessed.”

As Jews and as Americans, inheritors of the biblical tradition, we are to be a blessing.

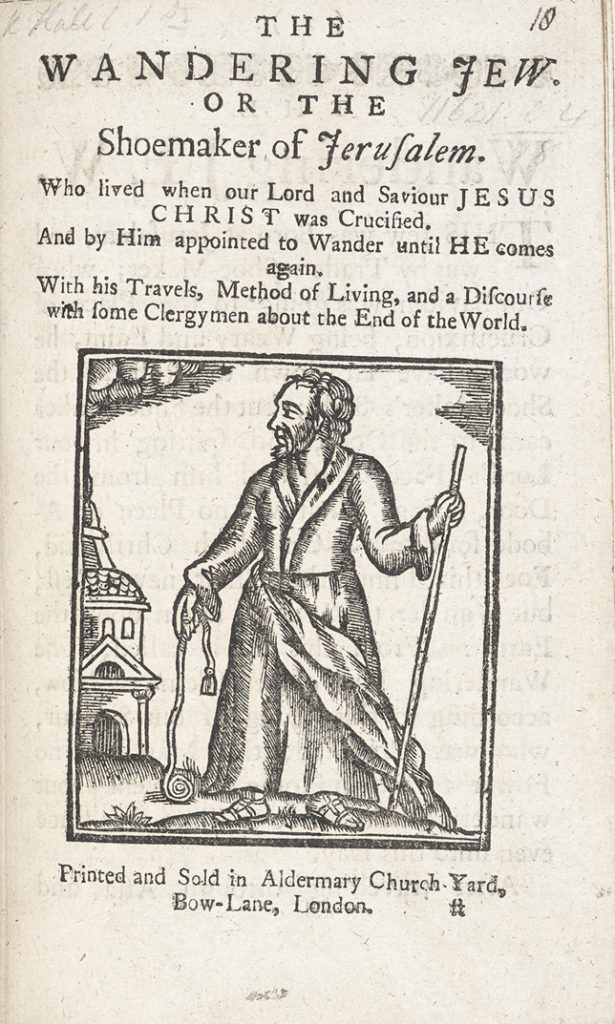

Antisemitic visions of The Wandering Jew

The identity of Jews as wanderers precedes the antisemitic canard of The Wandering Jew or The Eternal Wanderer. According to Holocaust scholar Michael Berenbaum, the image likely arose when most Jews rejected Christianity during the first centuries C.E. As a result, Jews were viewed as alien and “condemned to perpetual migration as a sign of divine disfavor.” In the 13th century, a more sinister fabrication appeared, writes book reviewer Alberto Manguel: as Jesus carried the cross, he stumbled in the doorway of a Jewish cobbler. The cobbler pushed Jesus from the doorway, telling him to move on. Jesus answered, “I will move on, but you will tarry until I return.”

— Candace R. Kwiatek

Literature to share

The Last Watchman of Cairo by Michael David Lukas. Infused with history, mystery, culture, and a delightful narrative style, this novel centers on the al-Raqb family, guardians of the Ibn Ezra genizah in Cairo since the 11th century. Woven into the story are the twin British sisters who helped rescue the genizah in the late 1800s along with Solomon Schechter. A highly engaging story with many layers to explore.

Color Me In by Natasha Diaz. Her dad is white and Jewish, her mom is black, and Nevaeh is torn between the two worlds as her parent’s marriage crumbles. This young adult book explores issues of fractured families, the complications of identity, the roles of religion, and the meaning of finding one’s own voice. A realistic, engaging addition to teen fiction.

To read the complete March 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.