Lev Golinkin on his memoir about leaving Ukraine

Two events in Dayton wrap up JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Series

By Joanne Palmer, The Jewish Standard

Somehow, when you think about it, you realize that we don’t really know much about how the Russian Jews got here.

We know a bit about the politics behind it. Those of us who are old enough to remember it firsthand know about the Soviet Jewry movement, about the refusniks and their mad courage, and about the Americans who smuggled them matzahs and Bibles.

But we don’t know what it felt like to be a Jew from the Soviet Union, or what it felt like to escape, or what it felt like to start a new life here.

There hasn’t been much written about it. Maybe it’s still too soon. Maybe there will be a torrent of novels and memoirs and films. Maybe someone had to start it.

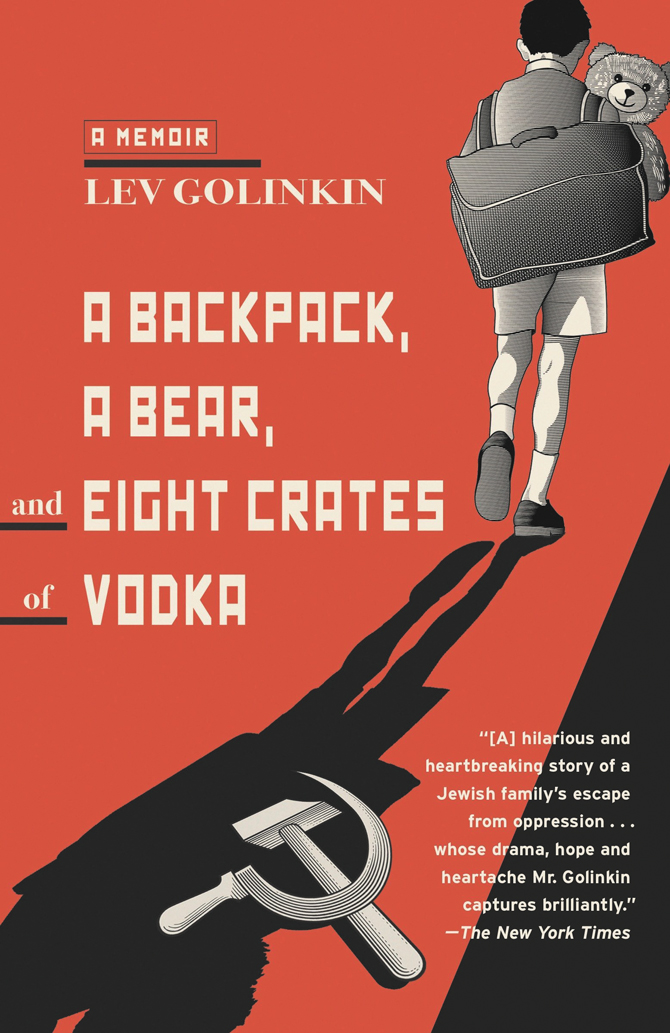

Lev Golinkin has written A Backpack, a Bear, and Eight Crates of Vodka: A Memoir, about his family’s exodus from Ukraine. The book was the Dayton JCC’s Community Read selection this fall, and Golinkin will present two events in Dayton Jan. 29 as the culmination of the Dayton JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Series.

Golinkin was 9 years old in 1989 when his family began the odyssey that ended in New Jersey. The backpack and the bear — Comrade Bear, genus stuffed, species cute — were just about all he could bring out, and the vodka went as bribes to the various terrifying people they encountered, whose outstretched hands would either take the offerings or use them as weapons against the family.

“You don’t have to be Jewish to read this book, but a big part of what I set out to do in this book is help American Jews understand what and who they fought for, and what and who they were fighting against,” Golinkin said. “I wanted to show why so many — not all, but so many — Soviet Jews came to the U.S. and then didn’t engage with the Jewish community.

“I can only speak for myself — most days I have enough trouble even doing that — and in the book I am very careful to speak only for myself — but I do realize that my family’s experience wasn’t unique. It was part of a pattern.

“I don’t think that American Jews, who live in a land of synagogues and Bar Mitzvahs, quite understand what a thorough job the Soviets did in extinguishing religion and culture,” Golinkin continued. “And two American organizations, HIAS and the JDC” — that’s the Hebrew Immigrant Aid Society and the Joint Distribution Committee — “not only helped us get out of the Soviet Union, they actually came in and worked to plant seeds in countries like Ukraine, Uzbekistan, and Russia, to help get Jewish life back there.

“In my home city, Kharkov, the synagogue was turned into a rec center, and now it’s a fully functioning Jewish center again. Religion was something that was illegal and underground — and now they have an Ask the Rabbi website.

“Imagine if you left the United States, and then you came back, and all of a sudden you learn that heroin is legal, and you can buy it on the street.” Judaism was like heroin, he suggested.

Why such an odd metaphor? Why compare Judaism to a deadly drug?

“Karl Marx said that religion was the opiate of the people,” Golinkin said. Beyond that, he wanted to show the depths of the hatred — and the resulting self-hatred — that came from the Soviet campaign against religion. “It was a very persistent campaign,” he said.

“They started with killing rabbis and community leaders, and they kept on eradicating everything.”

His background in the former Soviet Union “taught me that being a Jew was a disease,” he said. “The problem is, that idea goes all the way across the Atlantic with you, and I nurtured it long after the Soviet Union collapsed.”

All religion was sent underground, and priests, too, were hunted. Still, there was particular hatred aimed at the Jews, “who were persecuted not only for religion but also for ethnicity.”

“I think that Jews are probably the only people in the world where the name applies to both things,” he continued. “We had very little of religion by the time the 1980s rolled around, but everyone had to carry an ID card, and the fifth line was the line for ethnicity. You have to present your credentials to get anything. So imagine if your driver’s license said Jew.”

The Soviet Union was a huge place, he added. The levels of antisemitism varied depending on what other ethnic groups were around, how many Jews there were, and many other factors, including local history, and then the random whims of the people in charge. Where he was, when he was there, Jew-loathing reigned.

“My mom was a Jewish doctor. She had no problems. But my sister wasn’t allowed to go to medical school,” he said. “Policies varied. It was unpredictable.”

One thing that did not vary for Golinkin as a child was the hatred directed toward him at school. He often was beaten up, his friends called him names, and his parents, trying to protect him, kept him home as often as they could. Of course, to be fair, school, at least as he describes it in his memoir, was the sort of place that would make any sane child take to bed. It was highly regimented, purely polemical, imagination-averse, and actively unpleasant.

Much of life in the Soviet Union was actively unpleasant. He was a child when he left, so he must go by other people’s reports, but “people who know talk a lot about the sense of unreality in the Soviet Union,” he said. They were constantly told about their country’s glories, and how they would conquer all challenges.

“On the other hand, people in their living rooms were quietly derisive about the government, about Lenin, about everything. There was a very rich, sarcastic sense of humor that just pervaded everything. People often would say, ‘We pretend to work, and they pretend to pay us.’ This is a country that lost 20 million, at least, to World War II, and another 70 million to Stalin. The humor was really dark humor.”

Maybe because of that influence, Golinkin’s book, too, is darkly funny. At other times, it’s just straightforwardly funny. That sets off the darkness of his early life — filled with some periods of active fear, but even more with the dank boredom of the grim Soviet system.

People did not know that the system was on the verge of falling apart, Golinkin said. They knew that things weren’t going well, but instead of the problems leading to the end of the Soviet Union, they feared that it would lead to the end of the Jews. “One of the reasons we left was that when things go wrong, Russians and Ukrainians have pogroms. They blame everything on the Jews.”

When he and his family left, they were part of a huge wave of Jewish refugees who nearly swamped the systems set up to help them. Part of Golinkin’s story is about his long journey out, and then the family’s new life in the United States.

The decision to leave was an incredibly hard one, he said; he hadn’t realized how wrenchingly hard it was for his parents because he wasn’t old enough when they left. All he knew was that he desperately wanted to get out.

“Leaving was very dangerous,” he said. “You had to leave all of your belongings — you were allowed just a few nonessential items. You had no money. All you knew was that you had to get to some train station in Vienna. You have a one-way ticket. You just had to hope that someone would be there to meet you.”

In his book, Golinkin writes about the stratagems his parents had to use to get the paperwork that would allow them out; the emotional capital they had to expend, the buttons they had to push and the levers they had to pull — not to mention the actual money they had to pay, both over and under the table. They needed luck. They were lucky.

The trip out to the border sounds like an old Western. They went by bus, not stagecoach, but they had to worry about marauders hijacking the bus, robbing them, possibly even murdering them and throwing their bodies out into the bleak, featureless tundra through which they drove. Their stops had to be short, because that minimized the chances of being attacked. They had to pay off watchers who could warn them about raiders.

Once they got to the border, John Ford was replaced by Franz Kafka. The border check was terrifying and irrational. Not everyone made it out. The Golinkins did, but it was close — and his father, who tried to sneak out his intellectual capital, secreted on a computer chip, had to find a way destroy it, quickly and secretly. The stakes were far too high.

The skeleton of his book is formed from his childhood memories, fleshed out with a great deal of reporting work that he did as an adult. So some images are extremely intense, seen through the eyes of a preteen boy, and then they are given context.

The book then tells about the family’s stay in Austria, as they are moved around, taken care of but not told much, unsure of where they are going but very sure that they are headed in the right direction.

Golinkin’s father spoke English before he left Ukraine. “In the 1970s, when he was on his deathbed, my father’s father told my father, ‘One of these days, one of these years, one of these decades, this cursed country is going to collapse, and you will have the opportunity to get your family out, so you’d better get ready,’” Golinkin said. “So he learned English, and spent years honing it. That’s why he now has a job as an engineer. He’s about to celebrate his 25th anniversary at that.” His mother, who had not learned English before she escaped the Ukraine, has not been able to work as a doctor. “She’s now working as a security guard, but she’s very happy to be here, and to help the United States,” her son said.

Golinkin’s sister, called Lina in the memoir, learned English in Ukraine, and found it very useful. She’s an engineer in the Midwest. His grandmother, on the other hand, the fifth Golinkin in the group, “never really learned English,” he said. “But she was pretty old when she came here.”

Golinkin learned some English before he came to this country. The family’s first year was spent in West Lafayette, Ind. When the Golinkins and one other Russian Jewish family arrived, “it made front-page news,” he said. “It’s a small college town, and it was summer. Nothing happens there. An adorable puppy can make the front page.

“The Jewish community came together to adopt us, and they also involved the rest of the town. The whole town took us on. Both the good and the bad. And this happened in communities throughout the United States.”

His memories of school back in Ukraine, along with his inability to get along well in English, made his transition to school hard. “I was in the fourth grade,” he said. “There was nobody from the Soviet Union in school with me.

“But the teachers handled me wonderfully. They realized that I was terrified of school. I hated school. They didn’t speak Russian and I didn’t speak English. They realized that if they’d leave me alone in the back of the class, I would learn. They just gave me work to do and checked in with me at the end.”

West Lafayette is a university town, and his teachers were able to take advantage of that. “There was a grad student at Purdue who was working on a Ph.D. in English and was interested in education,” he said. She was matched with Golinkin, and “she figured me out,” he said. “She asked my dad what I liked, and he said English fairy tales. New ones, not Hans Christian Andersen stories, which I already knew in Russian. So she gave me fairly tales, and in order to get to the ending, I had to do the lesson.

“Eventually I trusted her, and we worked together for months,” he said; he recently tracked down his tutor, and learned that “she’s now the head of the English program at Michigan State University.”

The Golinkins’ stay in Indiana was short because “as soon as my dad started making money, he put it into resumes.” That led to the job in Trenton that he still holds, and the family moved to New Jersey. Golinkin graduated from high school there, and went on to Boston College.

Why did he choose a Jesuit institution? Specifically because it wasn’t Jewish. “I went there to escape my Jewish identity,” he said. “And then, while I was at Boston College, slowly, that changed. I needed to understand more. Toward the end of college, I had a serious conversation with a mentor there, and he said that I had to understand my past. That I have to know where I came from.

“He told me, ‘You need to stop telling people that you come from New Jersey.’ But that took time. I was driving out of New Brunswick once with friends, and the parking lot attendant had an accent. One of my drunk friends said, ‘Where are you from?’ and he said ‘New Brunswick.’ He asked him again, and the guy stared him down and said ‘New Brunswick.’

“I said ‘Leave him alone. He knows what you mean, and he doesn’t want to tell you.’ A lot of the time, Americans don’t know where they’re from. Often the people who come here know where they’re from all too well.”

Golinkin knew where he was from — but from a child’s vantage point. One of the reasons for this book was to give him the chance to see it as an adult.

“Part of it also was trying to reconnect with my Jewish identity,” he added. “I go to no synagogue, no temple, no nothing. But I am extraordinarily proud of being a Jew, of coming from a people who have the right to turn their back on the world but instead decide to engage and heal it.

“I feel most Jewish when I am working on a humanitarian project. One of the big gifts of writing this book is working with the JDC and HIAS. They helped my family, and they continue to help millions of others. It also helps me through volunteering and coming to terms with my past.”

The JCC Cultural Arts & Book Series presents Lev Golinkin at 7 p.m., Wednesday, Jan. 29 at the Dayton Art Institute, 456 Belmonte Park North, Dayton. Golinkin will discuss his views on discrimination past and present earlier in the day, at 1:30 p.m., in a conversation with Marshall Weiss at One Lincoln Park, 590 Isaac Prugh Way, Kettering, in partnership with JFS. Both programs are free.

To read the complete January 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.