One hundred years ago: an historic Zionist concert at Memorial Hall

Zimro’s Eastern European journey as newsworthy as its U.S. concerts

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

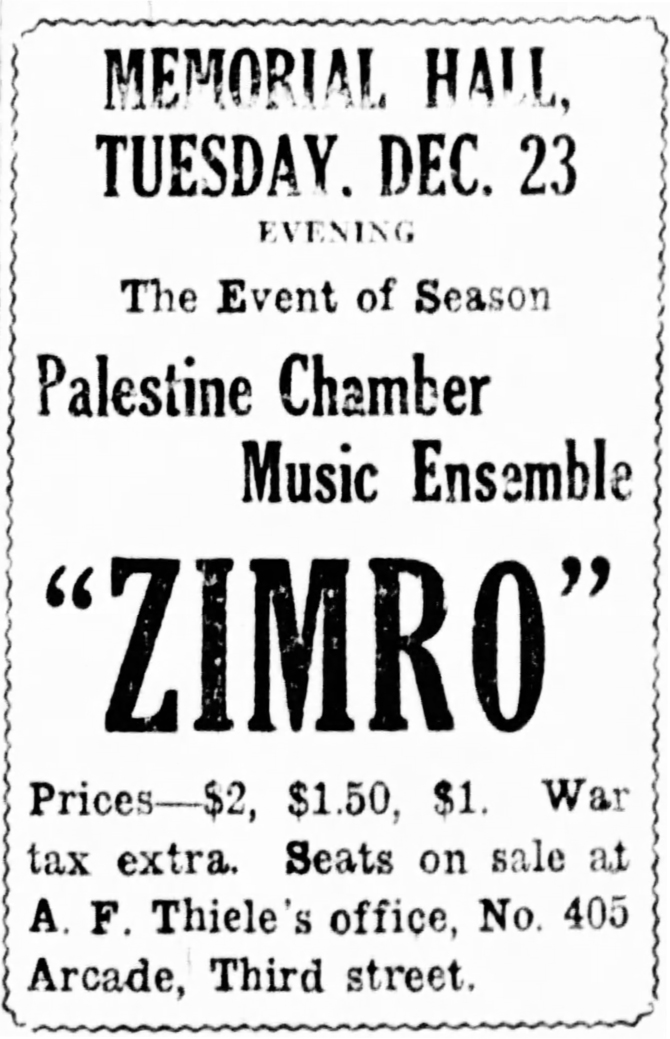

“An event of unusual interest is the concert tomorrow evening at Memorial Hall to be given by the Famous Palestine Chamber Music Ensemble known as “Zimro,” which is touring this country in the interest of an art and music temple in Palestine, under the auspices of the Zionist movement,” proclaims an article in the Dec. 22, 1919 Dayton Daily News.

This temple of art and music, the newspaper explained, would be a school for talented young men and women.

The Dayton Herald reported the six members of the ensemble arrived in Dayton Dec. 22 from Chicago and were on their way to the Hotel Gibbons before they were to perform Jewish folk music and Russian peasant songs the next evening.

A good night’s sleep for these Jewish musicians from Russia was more than warranted. Their journey to America for the tour turned out as newsworthy as their concerts here.

The musicians of Zimro — Hebrew for music of praise — were clarinetist S. Bellison, medal winner of the Moscow Conservatory, first violinist J. Mistechkin, violist K. Moldavan, second violinist G. Besrodny, cellist J. Cherniawsky, and pianist L. Berdichevsky — all graduates of the Petrograd Conservatory.

When they toured Russia in 1918 on their way to America, they experienced what the Dayton Daily News described as “the extremes of fortune.”

“They are one of the few artistic organizations who can boast of having actually toured the country at that time, when living conditions were impossible and transportation was even worse,” the newspaper reported Dec. 17, 1919.

Their journey played out like one of Sholem Aleichem’s tales. Mistechkin said Zimro’s accommodations across Russia were for the most part in freight cars, and they were fortunate if there was room for them to sit on a freight car floor.

“Ventilation, there was none and not infrequently there was a generous sprinkling of livestock,” he added. “The trains crawled along the countryside like slow oxen, sometimes taking five times as long as they should have to reach the destination.”

Things were looking up when they arrived in Perm, Russia on the day of a labor celebration. Zimro offered to perform for no charge, and “in return, the local soviet granted them a private coach for three weeks and they traveled ‘deluxe.’”

Then, once again, their luck changed for the worse.

As reported by George Robinson earlier this year in The New York Jewish Week, after Zimro journeyed eastward to Russia’s Pacific communities, “passing through war zones,” they were stranded in Shanghai for six months, waiting for visas to the United States.

Aron Zelkowicz, founder and director of the Pittsburgh Jewish Music Festival, told The Jewish Week’s Robinson that Zimro was the first proponent of the Russian school of composers “who incorporated East European Jewish folk material into an art music setting.”

Zimro’s tour marked the first time audiences in America heard Jewish melodies in a classical chamber format.

Zelkowicz, himself a cellist, brought musicians with the Pittsburgh Jewish Music Festival to New York for a loose recreation of Zimro’s sold-out 1919 concert there; the Pittsburgh musicians performed the centennial tribute this Nov. 4 at Carnegie Hall’s Weill Recital Hall.

Zimro’s musicians, staunch Zionists who toured under the auspices of the Central Zionist Organization of Russia, also performed in 1919 at the American Zionist Federation’s convention in Chicago.

In Dayton, Zimro’s program opened with the Star-Spangled Banner and closed with Hatikvah, the Jewish national anthem. In between, the audience heard Jewish music arranged for the chamber ensemble by its musicians, including freilachs, wedding music, and even Kol Nidre.

Clarinetist Bellison would become a naturalized citizen after he settled in the U.S. in 1921. He would later become first clarinetist with the New York Philharmonic.

Zionism in Dayton

Zimro’s concert in Dayton was sponsored by the Dayton Zionist District, which was established in 1909.

That same year, Dayton’s Ohave Zion (Love of Zion) society, then two years old, reorganized to become an Orthodox synagogue, which sought to have its members — and all Zionists in Dayton — purchase land in Palestine toward Jewish colonization.

In the 1919-20 American Jewish Yearbook, Ohave Zion’s address is listed as 20 Quitman St., with 62 memberships and 125 pupils. Ohave Zion even purchased a small portion of Beth Jacob’s cemetery for its members.

Ohave Zion seems to have faded away in the early 1920s; some of its leaders established the Conservative Dayton View Synagogue Center in 1923. Dayton’s two Orthodox synagogues, Beth Abraham and Beth Jacob, visibly supported Zionism. As was the case overall with Reform Judaism at the time, Temple Israel’s members were split on the issue, and its rabbis of the period were not Zionists.

With the collapse of the Ottoman Turkish Empire in World War I, British Foreign Secretary Lord Balfour’s declaration of the British government’s support for a Jewish state in Palestine on Nov. 7, 1917, and the liberation of Jerusalem by the British on Dec. 9, 1917, Dayton’s Zionists exuberantly joined Zionists around the world to do what they could to bring about a Jewish state.

By November 1918, the Dayton Zionist District had about 500 members. Dayton’s total estimated Jewish population at the time was 4,000. This support for Zionism came at the same time as Jews in Dayton canvassed to provide aid for the Jews of Europe, who languished in persecution during and after the First World War.

On June 16, 1919, Dayton Mayor J.M. Switzer chaired a “strictly non-sectarian” mass meeting at Memorial Hall “for the purpose of voicing the protest of Dayton against the massacre of Jews in foreign lands,” the Dayton Daily News reported.

On April 5, 1919, the Polish Army executed 35 Jewish residents of Pinsk. Earlier that year, in February, Cossacks launched a three-day pogrom in the Ukrainian city of Proskurov; 1,500 Jewish residents were murdered.

And on Dec. 18, 1919, the Dayton Daily News ran a report from Associated Press of a fresh wave of pogroms in the Ukraine, with approximately 5,000 Jews killed in Yekaterinoslav alone.

Four days after Zimro’s concert here, Dayton’s Jews filled Memorial Hall to raise $75,000 for the Jewish Relief Campaign.

Temple Israel’s Rabbi David Lefkowitz and Beth Abraham Synagogue’s Rabbi Michael Lichtenstein shared the story of the six million starving Jews of Europe — 800,000 of which where children — for whom the campaign was conducted.

According to the Dayton Daily News, Col. Edward Deeds and the Winters National Bank each donated $1,000 to the cause.

To read the complete December 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.