A Jubu-ish journey toward transcendence

A Bisel Kisel With Masha Kisel, The Dayton Jewish Observer

“You’re a Jubu!” exclaimed my friend Jaime, who was also Jewish and much more worldly than me. Jaime was coming through town on her way back to the University of Santa Barbara, where apparently “Jubus” were plentiful. I took her comment as a slight.

This spiritual awakening was uniquely mine and I felt, at the time, that it had nothing to do with the fact that I was Jewish. I was a sophomore at the University of Wisconsin in Madison, working on a South Asian studies degree, with a focus on religion.

My plans for college were to reach enlightenment, remain on earth as a bodhisattva and still graduate in four years. I was vegan, practiced intermittent celibacy, and regularly attended two-hour meditation sessions run by the campus Buddhist study group. I even lived alone to minimize worldly distraction. I practiced Buddhism as best as any Gen-X college kid could.

I only recently discovered that the term “Jubu” wasn’t Jaime’s invention and my spiritual thirst for something I could not find in Judaism as a teenager was in fact a wide phenomenon. What I didn’t expect was to learn that my Jewishness may have led me to the eight-fold path.

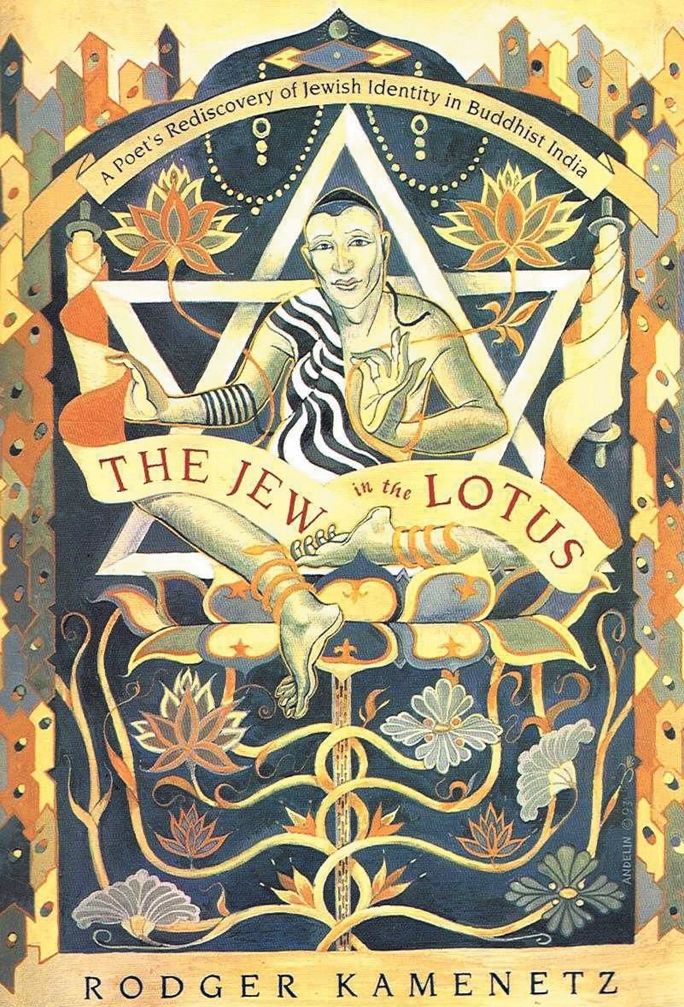

Rodger Kamenetz uses the term often in The Jew in the Lotus, his book about rediscovering his Jewish identity in Buddhism.

He writes, “…many spiritually curious Jews have explored Buddhist teachings, and some have left Judaism altogether. A surprising number have become spiritual leaders, teachers, and organizers in the Western Buddhist community.”

He goes on to show how Jubus have played an extraordinary role in popularizing Buddhism in the West.

Looking back, I now realize that many of the writers and thinkers I admired during my Buddhist phase were indeed Jewish. The poetry of Allen Ginsberg and other beat writers gave me an imagined community when I felt most alone.

More than that, they taught me that solitude was a precious resource that could quell my existential dread.

It was OK not to know why the world existed or whether or not there was a God. Years later, I discovered Mark Epstein, a Jewish psychotherapist who employs Buddhist philosophy to help patients recover from trauma. His beautifully-written Thoughts Without a Thinker and Going to Pieces without Falling Apart helped me deal with the debilitating anxiety of my post-college, soul-searching years.

As I began to wonder why so many Jews have been drawn to Buddhism, I recalled my own initiation into Jewish life as a young Soviet émigré.

Judaism came into my life as a demanding stepfather when I arrived in the United States. Judaism asked for obedience, even though I had no prior relationship with it.

It never told me why I should obey its authority. It certainly never answered the most important questions: Why am I alive? What happens after I die? Judaism offered me an iteration of God with whom I could not communicate.

In those early years in the U.S., Hashem’s watchful eyes only seemed to open when I was about to take a bite of a cheeseburger.

Kamenetz describes some of the Jewish Buddhists he met when he traveled to India with a Jewish delegation to meet with the Dalai Lama for an interfaith dialogue. One woman’s experience illuminated for me some of the reasons that my Jewish education “didn’t take.”

Kamenetz writes, “When I asked her about her knowledge of the Jewish mystical tradition, she said she might have been interested but it was never taught to her.”

I recall once when asked about what happens after death, the rabbi who taught Talmud at my school responded that for each good deed, Hashem will add a new piece of furniture to our spiritual home.

I didn’t want furniture. I wanted a transformative mystical experience that would help me see beyond the confines of the material world. I wanted to escape a reality where interior decorating mattered. After all, most of the furniture in our recently-settled refuge came from the garbage dump.

The notion that all life is suffering and that suffering comes from attachment to inherently impermanent things really appealed to me, in part because it mirrored my life experiences.

We moved constantly, people came and went. How could I continue ancient tradition when I was so unmoored? Buddhism offered me transcendence and autonomy. I didn’t have to pray to a father I didn’t know in a language I didn’t understand. I could be the captain of my own soul.

Interestingly, I came back to Judaism when I met my husband. Traditions that were previously meaningless became the basis of our life together. I also discovered that my impulses to question, to doubt, and to long for a spiritual plane are very Jewish indeed. My life today is full of routine and stability.

Nestled in a happily busy family life, I don’t think about those big existential questions as often. But I have new worries.

If before I felt as though the world wasn’t quite real, the current historical moment feels oppressive, inevitable. I find new comfort in the Buddhist notion of transience, which echoes King Solomon’s wise words in Jewish folklore: “This too shall pass.”

Dr. Masha Kisel is a lecturer in English at the University of Dayton.

To read the complete November 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.