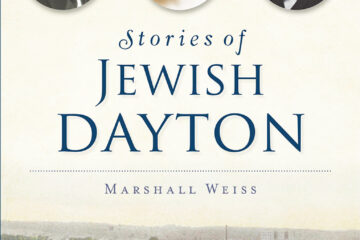

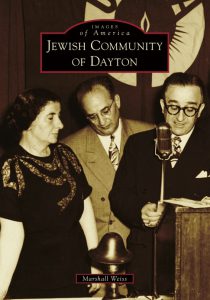

New book presents visual history of Dayton’s Jews

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

“He Who blessed our forefathers, Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob — may He bless this entire holy congregation along with all the holy congregations . . . and those who dedicate synagogues for prayer and those who enter them to pray, and those who give lamps for illumination and wine for Kiddush and Havdalah, bread for guests and charity for the poor; and all who are involved faithfully in the needs of the community.”

This prayer, from the Sabbath morning service in traditional Jewish liturgy, was at the front of my mind when I compiled the book Jewish Community of Dayton, released by Arcadia Publishing July 16 as part of its Images of America series.

From 1850 onward, Dayton’s Jews not only provided for the spiritual and material needs of their own, they also involved themselves faithfully in the needs of Dayton’s general community.

Jewish Community of Dayton offers a family photo album of the Jews of Dayton — more than 200 images — from those early days through the close of the 20th century.

My aim in the book isn’t to idealize but to help new generations discover glimpses of Jewish life in Dayton that might otherwise be forgotten.

My aim in the book isn’t to idealize but to help new generations discover glimpses of Jewish life in Dayton that might otherwise be forgotten.

America has provided unprecedented freedoms and opportunities for the Jewish people. This is the story of how they navigated these freedoms and opportunities — and the obstacles they overcame — in the Gem City of the Golden Land.

The earliest characteristic to divide Jews in America’s local communities was region of European origin. German Jews, who settled in Dayton first — at least a generation before the Jews of Eastern Europe — were at the top of the Jewish community, socially and philanthropically, at least until the other groups acclimated and caught up.

Eastern European Jews had their distinctions too. If a Russian Jew married a Lithuanian Jew, it was practically considered an intermarriage.

After World War II, when American Jews became aware of the horrors of the Holocaust, these distinctions faded significantly.

Even amid religious distinctions, the obligation of Jews to take care of each other has bound the Jews of Dayton.

Immediately after the Great Flood of 1913, Max Mann, who owned the only kosher slaughterhouse in the city, was forced to suspend operations temporarily. Harry J. Jacobs, a Reform Jew who owned a nonkosher meat storage plant in Dayton (presumably spared in the flood), placed his establishment at the disposal of the Federation of Jewish Charities so that “the strict ‘Kosher’ meats may be obtained by the Jews of the city,” according to the Dayton Journal.

At the time, the Federation was led by German Jews from Dayton’s Reform community. A month later, at Passover, the Federation distributed 10,000 pounds of matzah to Dayton’s Jews in need — those who already lived in poverty and those who had lost so much in the flood. Matzah was particularly scarce; soon after the flood, hungry citizens of Dayton seized six train cars of matzah when regular bread could not be found.

The Dayton Journal reported that “the entire population depending upon this relief station fell back upon this unleavened bread. Catholics, Protestants and Jews alike clamored for it when other bread supplies were scarce.”

Did the early Jews in Dayton encounter prejudice? Certainly. At every turn? No. In a 1981 interview with Lisa Denlinger for a Wright State University project, retired attorney Benjamin Shaman, then 89, put it best: “As I grew up, I was taunted by my Catholic schoolmates. In Russia I would have been punished for fighting back whereas in America I could fight back.”

Shaman would go on to serve his congregation, Temple Israel, and the Jewish Federation in virtually every key leadership position. He would also chair Dayton’s school board and serve as president of Barney Convalescent Hospital, now Dayton Children’s Hospital.

What will future generations record of us when we are nothing more than history? That will depend on how we carry Jewish life forward for our benefit, and theirs.

Adapted from Jewish Community of Dayton, Images of America, Arcadia Publishing, 2018.

To read the complete August 2018 issue of The Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.