A cautionary tale of McCarthyism, on film

By Marc Katz, Special To The Observer

To most of us, the 1952 Gary Cooper/Grace Kelly film High Noon is a classic Western about nothing more than an ex-convict threatening the sheriff who put him in jail.

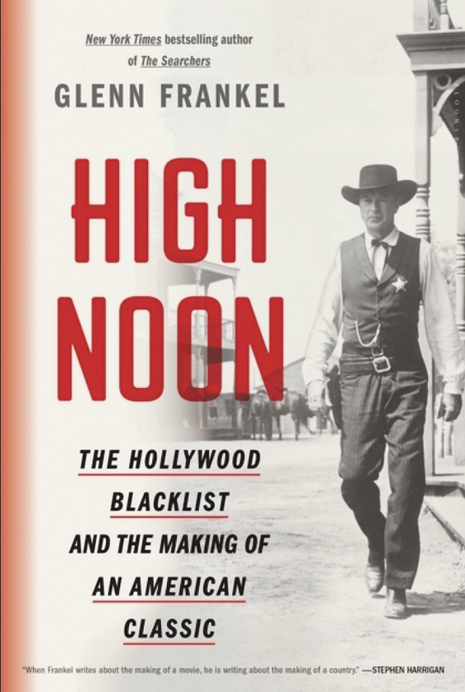

It was much more than that, as Pulitzer Prize-winning journalist Glenn Frankel points out; it not only serves as an allegory for the congressional hearings of the House Un-American Activities Committee, it has a strong resemblance to what’s happening in our federal and local governments today.

Frankel, author of High Noon: The Hollywood Blacklist And The Making Of An American Classic, will lead a screening of High Noon followed by a talk at The Neon on Nov. 15 as part of the JCC Cultural Arts & Book Fest.

In a telephone interview while on his book tour, Frankel said the film — co-written by Carl Foreman, who was called before HUAC as he worked on the screenplay — is a parable of how Hollywood became involved in Sen. Joe McCarthy’s “red scare” hearings, leading several in the U.S. film industry to become blacklisted.

Behind HUAC’s machinations was attorney Roy Cohn, who not only advised McCarthy during the hearings, but later, pre-President Donald Trump.

“He (Trump) certainly learned from that guy (Cohn),” Frankel said. “He mentors (Trump’s) view of the world: it’s a bad place, everyone’s out to get you, (and) you have the tools and weapons to get them first. Somebody punches you, you take out a gun and shoot them. You escalate, go to court, sue. Federal government’s investigating? You sue them. That kind of bully boy tactics.

“Trump was certainly ripe for that. Roy Cohn actually showed him the way to do it. You get a guy who doesn’t pay his bills, who can justify any act, because you can get away with it.”

In Foreman’s hearing, he admitted he had previously joined the Communist Party but didn’t stay; he would not name others. Afterward, he was unemployable domestically and moved to London, writing under pseudonyms.

His name was even struck from High Noon’s credits.

Frankel, a Rochester, N.Y. native, graduated from Columbia University, worked his way to the Washington Post in 1979, and eventually became the Post’s bureau chief in South Africa, Jerusalem and London (twice).

He was awarded his Pulitzer Prize for international reporting on Israel and the Middle East.

He later became editor of the Washington Post Magazine. The New York Times bestselling author has taught journalism at Stanford and the University of Texas.

What made the Hollywood blacklist especially bitter, Frankel explained, was the fracturing of friendships.

“A number of them simply never worked again,” Frankel said. “The blacklist lasted longer than expected and did more damage. Those are the wounds that do not heal — when your business partner names you, or one of your best friends. Just about all of them have passed away now, but among their children, they’re raw and can’t be healed.”

Frankel said the 1950s were not as serene as we like to remember them.

“It’s supposed to be an era of social rest. The ‘50s were a time of great tensions and anxieties. Every era in American history is a complicated and turbulent time. In a democracy, you constantly revisit the past. The past is not over. It isn’t even the past.”

He described the McCarthy era as a time when a growing number of Americans said they were disenfranchised and wanted to get their country back.

“In those days, it was (from) the communists, Jews and liberals. Today, it is the Islamic terrorists, undocumented immigrants, the new neo-populist community, Muslims and the LGBT community, anyone who doesn’t share a certain identity.”

The JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Fest presents author Glenn Frankel and a screening of High Noon at 7:15 p.m. on Wednesday, Nov. 15 at The Neon, 130 E. 5th St., Dayton. Tickets are $9 and are available at jewishdayton.org, by calling 610-1555, or at the door.

To read the complete November 2017 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.