The mystical power of memory

By Rabbi Joshua Ginsberg, Beth Abraham Synagogue

A Chasidic legend tells us that the great Rabbi Baal Shem Tov, Master of the Good Name, also known as the Besht, undertook an urgent and perilous mission: to hasten the coming of the Messiah. The Jewish people, all humanity were suffering too much, beset by too many evils. They had to be saved, and swiftly. For having tried to meddle with history, the Besht was punished; banished along with his faithful servant to a distant island. In despair, the servant implored his master to exercise his mysterious powers in order to bring them both home.

“Impossible,” the Besht replied. “My powers have been taken from me.”

“Then, please, say a prayer, recite a litany, work a miracle.”

“Impossible,” the master replied, “I have forgotten everything.” They both fell to weeping.

Suddenly the master turned to his servant and asked: “Remind me of a prayer — any prayer.”

“If only I could,” said the servant. “I too have forgotten everything.”

“Everything, absolutely everything?”

“Yes, except the alphabet.”

At that, the Besht cried out joyfully: “Then what are you waiting for? Begin reciting the alphabet and I shall repeat after you…”

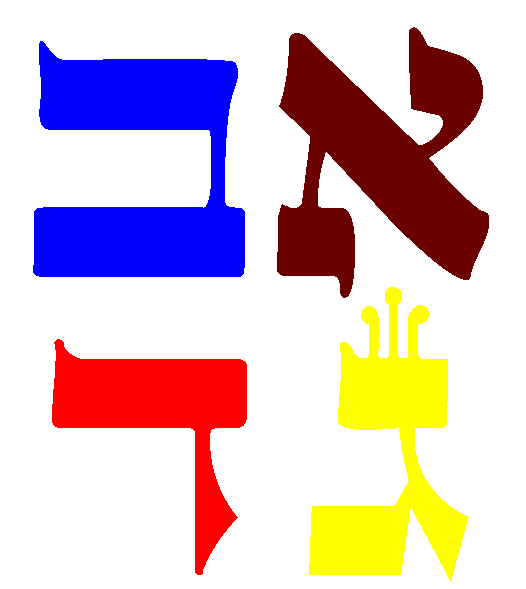

And together the two exiled men began to recite, at first in whispers, then more loudly: “Aleph, bet, gimel, dalet…” And over again, each time more vigorously, more fervently; until, ultimately, the Besht regained his powers, having regained his memory.

Elie Wiesel, of blessed memory, commenting on this legend says:

“I love this story, for it illustrates the messianic expectation — which remains my own. (It reflects) the importance of friendship to man’s ability to transcend his condition. I love it most of all because it emphasizes the mystical power of memory. Without memory, our existence would be barren and opaque, like a prison cell into which no light penetrates; like a tomb which rejects the living. Memory saved the Besht, and if anything can, it is memory that will save humanity. For me, hope without memory is like memory without hope.”

Memory is part of our Jewish DNA. In fact in our tradition, remembering is a religious imperative, because memory transmits ethics, morals, peoplehood and potential.

For the Jew, the main reason to remember the past is that it continues to live in the present, influencing who we are today. Memory is the key to the future, or as the Baal Shem Tov said, “In memory lies the secret of redemption.”

This is because memory is not the same thing as history. Of course, we are deeply concerned with the facts of where we come from and how we came to be here.

This is why my education at the Jewish Theological Seminary was very focused on the history of the Jewish people. But unlike history, memory is more than simply recalling the past.

Rather, in Judaism, the past is very much alive in the present. Memory defines us and gives meaning to our lives. We see the past through the prism of faith. And memory creates community. Leon Wieseltier, longtime literary editor of the prestigious magazine, The New Republic, and observant Jew, put it this way:

“In the age of tradition, the past was present. It was one of the primary purposes of Jewish ritual and liturgy to abolish time, to make Jews divided by history into contemporaries and those divided by geography into neighbors; in this way, the many communities of Judaism were unified into a single people and the experiences of many Jews into a single story.”

This is why I believe, it is no accident that liturgically, the upcoming High Holy Day of Rosh Hashanah is known as Yom Hazikaron, the day of memory.

One of the main sections of the Musaf Amidah prayers is the Zikhronot — verses of remembrance. Rosh Hashanah is a day when we help each other remember as a community; together we remember and hope to be remembered by God.

But Rosh Hashanah is also the New Year — a day of rebirth and potential. Our people celebrate Rosh Hashanah as a day in which we both remember and look forward. Memory and renewal are inextricably linked by this day. One requires the other.

This is why remembering is a sacred and necessary act. This is why no commandment figures so frequently, so insistently, in the Torah.

The biblical figure Job exhorted: “Please inquire after first generations and continue the learning of your ancestors (8:8).”

Memory is not mere record but a process of learning and making meaning from the memories of the past into our present life. That is what Jewish memory does, and that is how it pushes us all to be better and more resilient than we would be otherwise. Jewish memory is not about retention but redemption.

May this Rosh Hashanah, this Yom Hazikaron, this day of memory, and this High Holy Day season as a whole, help us remember what was good and what was bad: how we will preserve the good in the year to come and how we will transform the bad into positive things to push us forward.

Let your memories, and our shared Jewish story, guide you from within and without. If you have trouble remembering, turn to your friend, your loved one, your children, your grandchildren, or the person next to you, and together we will remember that it is still possible to be better, that it is possible to make our community and our world better.

Though at times it may feel as though the Jewish people and all of humanity is suffering too much, and we are beset by too many evils, each of us — through the good deeds we do — possesses the ability to tip the world’s balance into righteousness and redemption. This is what we should always remember.

To read the complete September 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.