Shavuot and revelation

By Rabbi David M. Sofian, Temple Israel

Lately I have been rereading Rabbi Neil Gillman’s book, Doing Jewish Theology. I doubt Neil Gillman’s name is one that most of you readily know. It is worth knowing, because he can be an extremely helpful philosopher/theologian. Gillman spent his entire professional career teaching at Jewish Theological Seminary (the Conservative movement’s rabbinical seminary) in New York, from which he retired a few years ago. Perhaps you are thinking at this point: what is a Reform rabbi doing reading a JTS (Conservative) philosopher? Truth is, rabbis read thinkers from all the movements all the time.

Let me just mention a couple of his earlier works: Sacred Fragments: Recovering Theology for the Modern Jew (1990), for which he won the national Jewish book award, and The Death of Death: Resurrection and Immortality in Jewish Thought (1997).

I find him particularly helpful because he so often focuses on the metaphors through which we think about God. Among all the many insights I’ve gained from reading his work, I am particularly fascinated by his discussions of revelation and how what we think about that determines also what we think about authority in Jewish life.

I won’t try your reading patience with any details here about his or for that matter my thinking on the subject. Instead I want to raise the subject generally as the appropriate Jewish thing for all of us to be thinking about around this time of year.

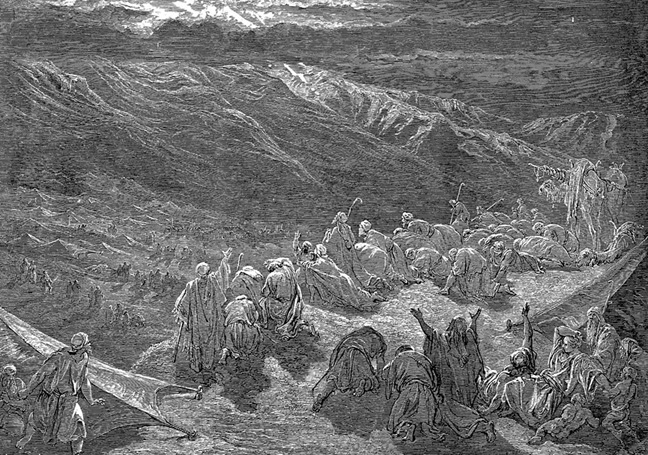

As I write these words, we have begun counting the Omer, those days between the beginning of Pesach and Shavuot. According to our tradition these are the days when our ancestors, having left Egypt, were on their way to Sinai to receive the Torah. The redemption from Egyptian slavery is only complete and meaningful once the Covenant with God is concretized in the revelation embodied in Torah. This means that this time of year is when we are preparing for Shavuot.

The Torah teaches us that Shavuot originally celebrated the first fruits of the land brought to Jerusalem in thanksgiving to God. The rabbis of the Talmud added that this time was also the time of the giving of the Torah. Given the centrality of Torah (study and practice) in Jewish life, it is always sad to me that this festival is something of a stepchild in modern Jewish observance.

There are probably many reasons for this including its lack of colorful observances like the Seder. But the one that stands out in my mind is that it is so theologically challenging. As modern Jews, it can be difficult to think about subjects like revelation, Torah and God. Perhaps this is why we don’t readily engage.

My hope is that you will resist our tendency to disengage and use this time of year to ask yourself hard questions about what you really think about God, Torah, and Jewish practice. If you are willing to engage in that kind of serious thought at this season of Shavuot, the festival will take on new and greater significance. If you want Neil Gillman’s help in your thinking, his books are ready and waiting.

To read the complete May 2015 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.