John Patterson, NCR, Oakwood, and the Jewish community

The historic record shows that his known legacy of racial discrimination is replete with surprising contradictions

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

The city of Oakwood is home to about 160 identified Jewish households, approximately 10 percent of the Miami Valley’s Jewish community.

Chabad of Greater Dayton is prominently located there, at the corner of Far Hills Avenue and Grandon Road. Beth Abraham Synagogue, Hillel Academy of Greater Dayton Jewish day school, and the Miami Valley Mikvah (ritual bath) are at Sugar Camp, formerly NCR’s international training center in Oakwood.

Oakwood is an anchor of today’s Miami Valley Jewish community. That was hardly the case a century ago, as I’ve been reminded from the time I arrived in the Dayton area nearly 25 years ago, and especially when I was working on my book, Jewish Community of Dayton, a few years back.

Before and immediately after the book’s publication, I gave several talks about various aspects of the Dayton Jewish community’s history. At each Q&A, Jews in our community gravitated toward the same topics: John Patterson, NCR, Oakwood, and their antisemitism toward the Jews of Dayton. The starting point for all of these discussions was the presumed antisemitism of each.

I only touched on Oakwood’s racial restrictions briefly in my book. It’s a topic worthy of in-depth exploration.

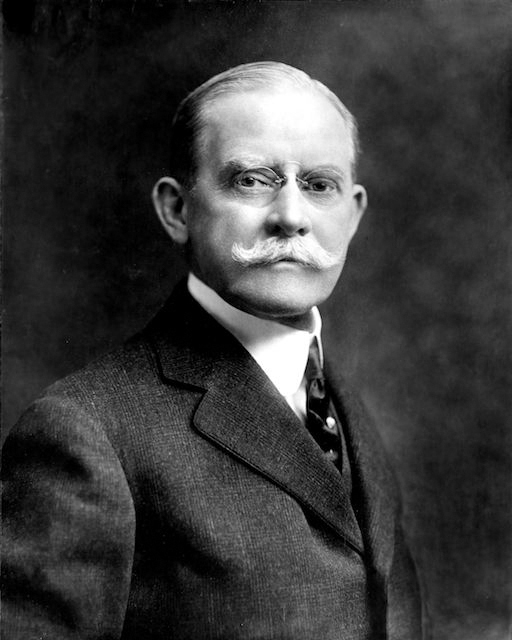

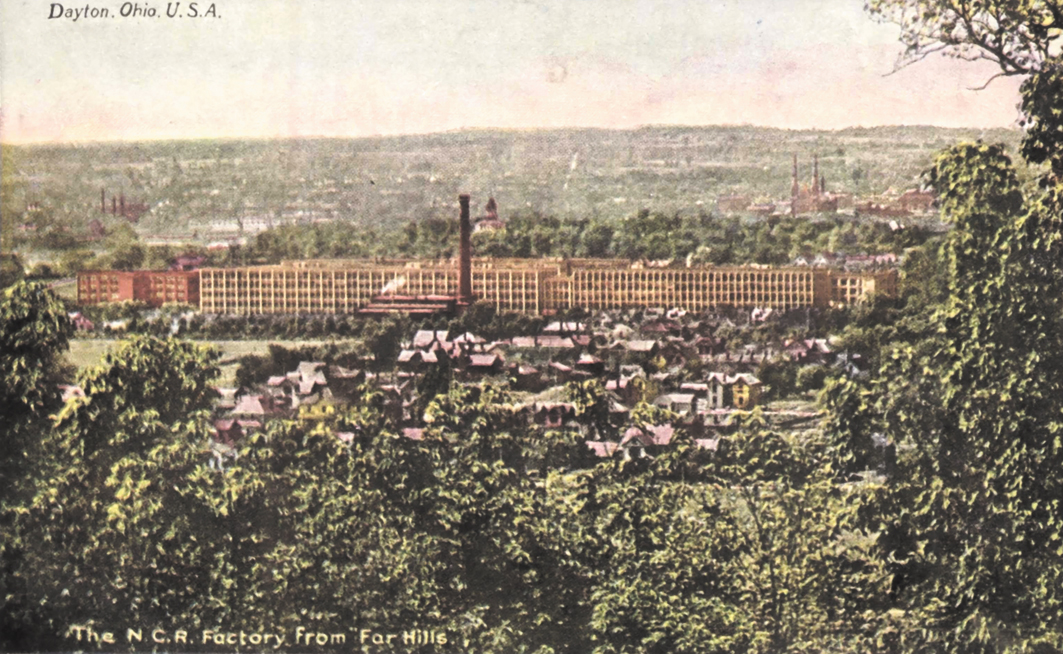

John Patterson, born in 1844, was the founder, owner, and manager of National Cash Register, which he began in 1884. He is considered the Father of Oakwood, established as a village in 1908. He died in 1922.

From the era of Patterson’s rise with NCR and through his passing, Dayton’s Jews fell out into two groups. The first to arrive were German Jews beginning in the 1840s because of antisemitism. By the time Patterson was laying the foundations for NCR, Dayton’s German Jews were mainly successful merchants who worshiped downtown at the Reform B’nai Yeshurun (now called Temple Israel). Until the flood of 1913, they tended to live in the area of North Robert Boulevard downtown. They also had their own social club, The Standard Club, not far from B’nai Yeshurun.

Beginning in the 1880s, impoverished Jews from Eastern Europe arrived in America with the Great Wave of Jewish immigration. They were driven by brutal pogroms and antisemitic restrictions in czarist Russia. In Dayton, they settled in the East End, along Wayne Avenue between Fifth and Wyoming Streets. Jews who came from Lithuania worshiped at Beth Abraham Synagogue, those from everywhere else across the Russian Empire prayed at Beth Jacob Synagogue. For a dozen years beginning in 1909, an Orthodox Zionist synagogue, Ohave Zion, also met in the East End.

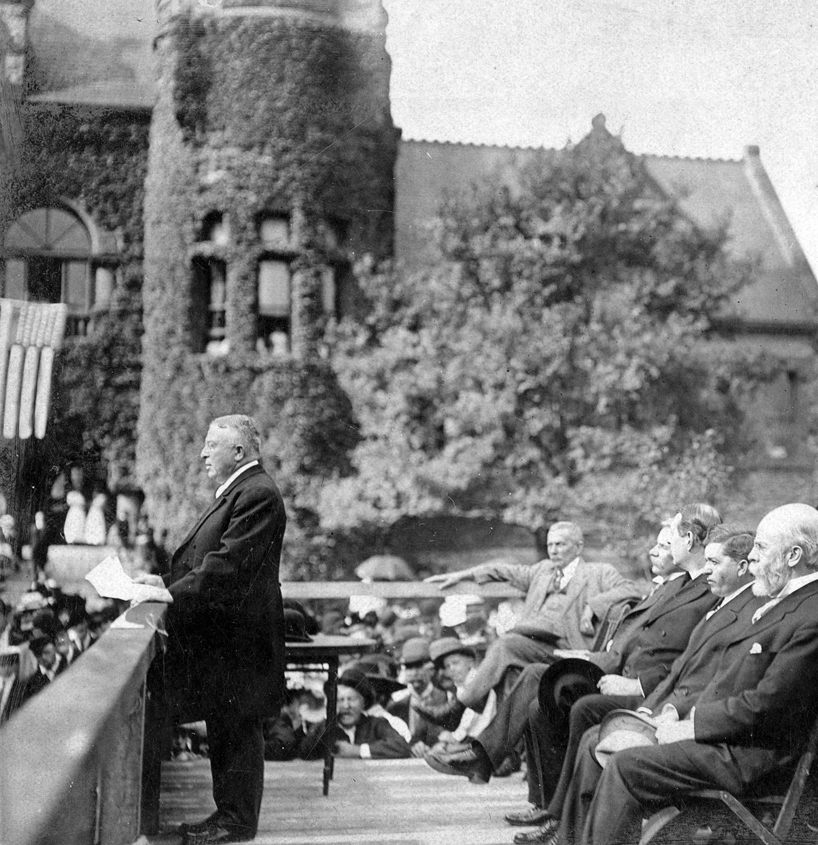

For those not too familiar with Patterson, these excerpts from a speech that a community leader gave at the time of his death paint a clear picture of this first citizen of Dayton:

“He was a passionate lover of his city, raising his voice and spending his effort toward its betterment, the purification of its politics and the beautification of its streets…A true leader of men, he took command on that dark night in Dayton in March 1913, when the levies broke and the waters of the Miami poured into the homes of over half the people of the city. He turned the force of men that he had trained into making cash registers into making boats, one a minute, and then sent them into the waters to feed the marooned population, and to take out to safety the sick and the aged, turning his great factory into a hospital and a refuge.

“But more than that, he will be remembered because of his industrial conscience. He was not willing to degrade his workers to the level of animals and take away their self-respect. So he pioneered for better factory conditions…He wanted to give his workers a chance to rise, so he educated them, offered them the means to advance…I remember with what joy he spoke to me of the arrangement that he was making for profit-sharing among the workmen. This is John Patterson’s monument, this great exemplification of the industrial conscience, his factory. And another would be the city which he loved with a deep passion.”

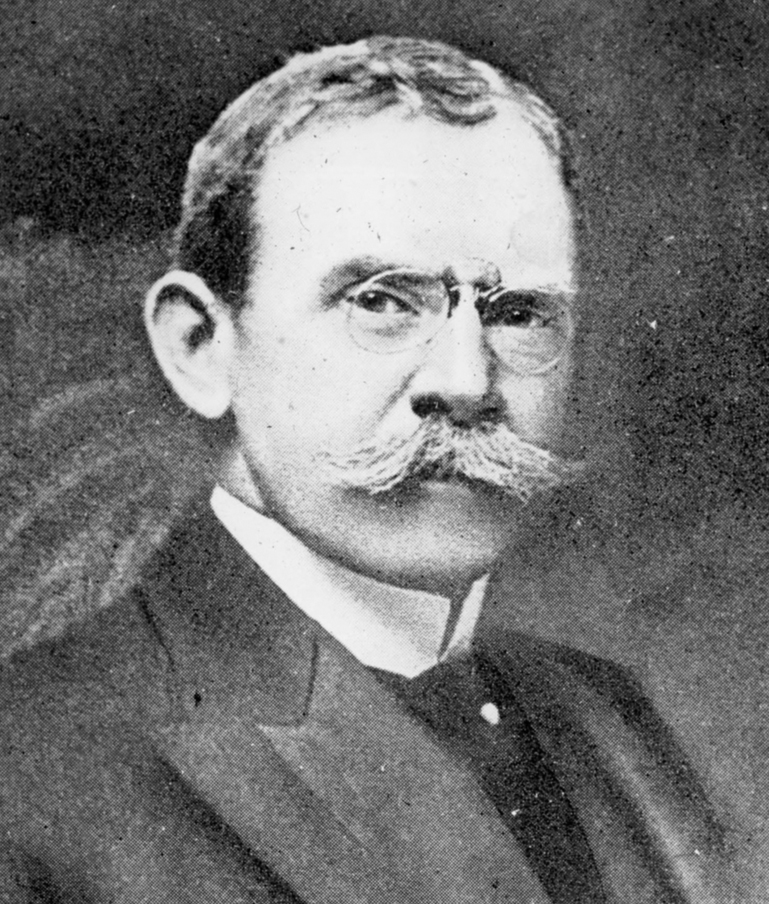

The person who said this of Patterson was a Jew: Rabbi David Lefkowitz, who had led B’nai Yeshurun in Dayton from 1900 to 1920. Lefkowitz gave this sermon from his new pulpit, Temple Emanu-El in Dallas.

This is the same John Patterson whose management team, at least in America, was all White and generally Protestant. A natural outgrowth was the village of Oakwood, an idyllic haven for Patterson and his executives, welcome only to White Christians.

The historic record is full of surprising contradictions. In the public square, Patterson did work with leaders in Dayton’s Jewish community. And the public country club he gave to the city of Dayton was open to all of its citizens in some form or another. But the legacy of his prejudices and how racial restrictions played out at NCR and in Oakwood linger in the collective memory of Dayton’s Jews.

This has even led to local legends about Patterson and the Jews, stories that are not factually, historically correct but offer those who pass them on some imagined justice against racial restrictions.

Here is what we know from the historical record.

Advancement for some

African Americans were hired at NCR at least in the beginning, as janitors and in the foundry. Jews were able to work in the factory and in clerical positions.

Along with photographic evidence of African Americans at NCR are two letters — written in 1904 and 1905 — by S.J. Gorman, foreman of NCR’s janitors. In both, Gorman writes, “My janitor force are all colored men and there are 75 of them.”

Mark Bernstein, author of Grand Eccentrics — Turning the Century: Dayton and the Inventing of America (1996), explained to The Observer that Patterson thought of NCR as a meritocracy. But at the same time, his version of logic led him to eliminate his African American employees.

“He believed every employee could rise to the top,” Bernstein said. “At one point, he concluded that since White employees would not work for a Black supervisor, Blacks could not be promoted and therefore had no real future with the company. So he fired them. My best guess is that this involved about 200 black employees out of a total labor force of 5,000 to 6,000. My best view is that this happened sometime between 1905-1910.”

In a 1985 oral history project the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton facilitated, one participant, Charlie Froug, talked about his father, Israel Froug, and Charlie Froug’s uncle, Charlie Vangrov. In 1913, both were carpenters in Cincinnati.

When the flood hit Dayton that year, Israel Froug and Charlie Vangrov came from Cincinnati for two weeks to work at NCR, initially building boats. The two thought Dayton was the most beautiful city they had ever seen.

Israel Froug came to work for NCR in 1915. Charlie Froug recalled of his father, Israel: “He was fired the first week he was there. He was shomer Shabbos (Sabbath observant). He wouldn’t work on the Sabbath and was given a pink ticket when he came back on a Monday. He was wild that day and went to John H. Patterson and called him an antisemite, with his real honest-to-God Yiddish accent. John H. was upset and wanted to know why. He told him, ‘I didn’t come to work on Saturday: that’s my Sabbath. I’ll work on your Sabbath if you’ll keep the plant open.’ Patterson made a deal. If he could make the number of pieces in the five days that the other men did in six, he didn’t have to come in on Saturdays.” Israel Froug accepted.

Before Benjamin Shaman became a prominent attorney in Dayton, his first job after he graduated Stivers High School in 1909 was as a stenographer for NCR. Born in Russian Poland, Shaman shared his story in a 1981 oral history project for Wright State University facilitated by Lisa Denlinger.

The Father of Oakwood

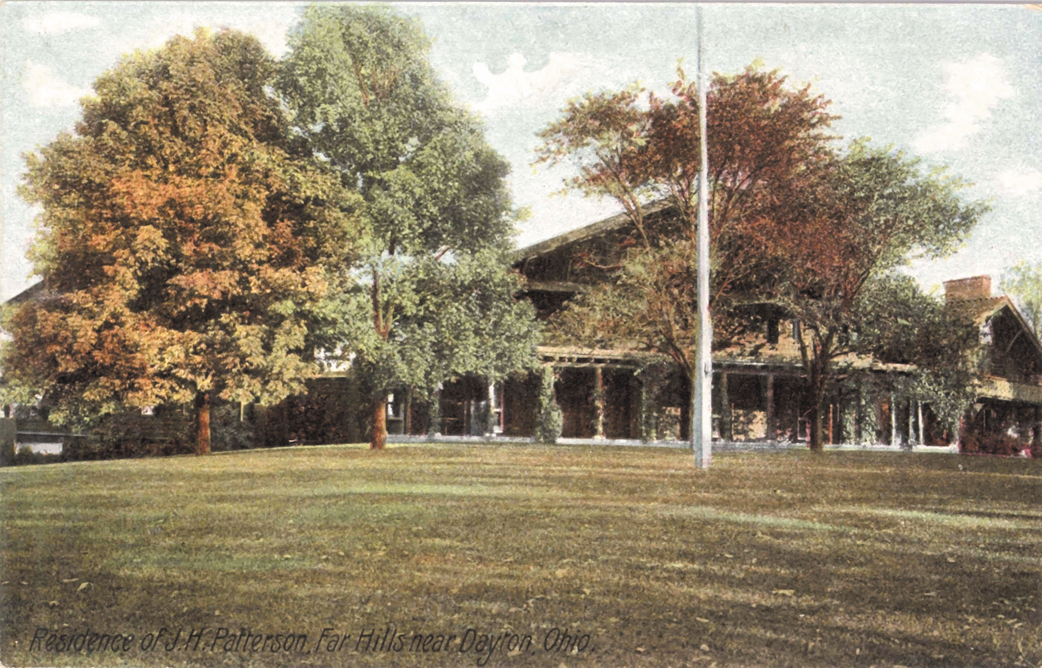

Bruce W. Ronald and Virginia Ronald explained in Oakwood: The Far Hills (1983) that before the turn of the 20th century, Patterson built The Far Hills, his summer home, on the shade-covered hills of what would become the village of Oakwood.

“Patterson’s paternalism began to spread to Oakwood,” the Ronalds wrote. “First he encouraged his executives to move there. Later Patterson would encourage his foremen to move to Oakwood as well. His method of enticing people to the village was simple. With the terms available, his employees could not afford to live elsewhere. The overall price was low, the down payment practically non-existent and the monthly payments negligible.”

Patterson made this possible when he contracted the John B. Stetson Building and Loan Association of Philadelphia to serve as the building and loan association for NCR employees. The arrangement was proclaimed in the July 1898 American Building Association News.

This building and loan association had been established in 1880 by legendary hat maker John B. Stetson for his factory employees, to help them “in building their own homes, and to encourage them in saving money for that purpose, and for the benefit of their families.”

Gorman’s letters of 1904 and 1905 inform us that NCR’s building association was not used by the “working men and women at the factory.” Rather, they “don’t live, and won’t, in any particular district. They prefer neighborhoods which they select themselves for their own reasons, and they prefer houses built in such places, and such ways, as suit the individual taste.”

The foreman continued: “There has never been any inquiry whatever from the Company as to how these men live, or where. The men prefer to take care of themselves, and are able to, in the matter of housing, and in their own way. They need no assistance from the Company on the subject. The building associations in Dayton are many; they are all, or nearly all, very good.”

It’s not known whether this arrangement of building association use exclusively for NCR executives and foremen was according to Patterson’s design or if that’s just how it fell out.

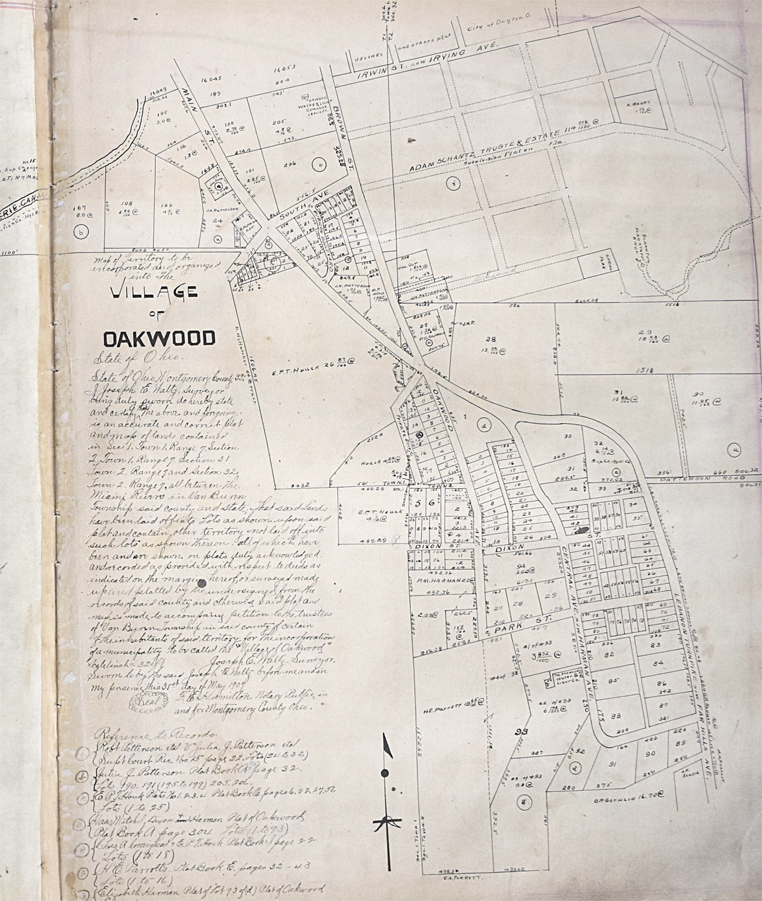

When Oakwood had enough residents to incorporate as a village in 1908, Patterson’s name was at the top of the incorporation documents.

“Once he got into his head to plan for the future of Oakwood, there was no aspect of the community that didn’t bear his mark or receive his advice,” wrote Joanne K. McPortland in Oakwood, From Acorn to Oak Tree: A Centennial Celebration 2008.

Racial residential restrictions

It wasn’t until after the Great Dayton Flood of 1913 that Oakwood experienced growth as a “high and dry” community for Dayton’s well-to-do citizenry. And Oakwood didn’t truly boom until the 1920s.

Before the flood, Dayton’s fashionable set lived along Robert Boulevard, which followed the contour of the Miami River’s east bank downtown. The emerging affluent suburbs on high ground then were Dayton View and Oakwood, both accessible by a trolley line.

Those familiar with Dayton’s Jewish history know that discriminatory real estate restrictions kept Jews from living in Oakwood. Jews with the means to do so moved to Dayton View, and some led the way there in the years before the flood.

There’s even documentation that the Wright family — which had initially purchased land in March 1910 for a new home at Salem Avenue and Harvard Boulevard in Dayton View — ultimately decided to build its house at Harman and Park Avenues in Oakwood at least in part out of concern that Jews were moving to Dayton View.

On May 7, 1911, Orville Wright wrote in a letter to his brother Wilbur that a soon-to-be neighbor of theirs on Harvard Boulevard had advertised in that morning’s Dayton Journal that he was selling his property.

“We are afraid it will be sold to some friend of our conspicuous Hebrew neighbors,” Orville wrote.

This was in addition to design challenges they encountered because of the size of the lot.

Katharine Wright, Orville and Wilbur’s sister, wrote to family friend Griffith Brewer on Nov. 8, 1911, “I think Will and Orv are very glad we did not go ahead on the original lot. Many things are making that neighbourhood rather undesirable.”

What exactly were the racial restrictions south of Dayton, and how did they play out? Two tools to put racial housing restrictions on lots in Montgomery County were to include them at the plat level or at the deed level.

The first discriminatory real estate restrictions in Montgomery County are recorded at the plat level in Van Buren Township; the township no longer exists. Parts of Van Buren Township became Oakwood beginning in 1908, and the remainder became Kettering (1952) and Moraine (1953).

Montgomery County’s first plat with discriminatory restrictions was recorded by the county Oct. 6, 1924, “in accordance with the rules and regulations adopted by the Director of Public Service of the City of Dayton, Ohio, acting as Supervisor of Plats under Sec. 136 of the Charter of the City of Dayton, Ohio, and the same is hereby approved.” Though this plat was in Van Buren Township, not Oakwood (today it’s in Dayton), the developers capitalized on the marketing appeal of Oakwood in the plat’s name, McKnight’s East Oakwood Plat.

The developers and their lender, the Permanent Building and Savings Association, received approval for the platting with a racial restriction they included: “That in consideration of the price at which property is sold the said purchaser agrees not to sell, transfer, lease or rent said property to any person other than of the caucasian race.”

This language also excluded Jews. White America at that time didn’t consider Jews to be Caucasians. Italians were also included in the non-White construct of the times.

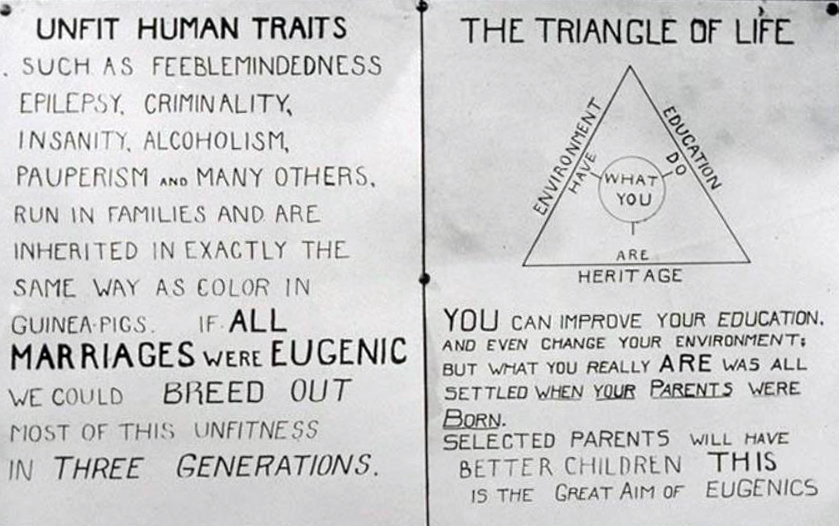

In the 1920s, the pseudo-science of “eugenics” — the racist pursuit of scientific proof of inferior and superior races championed by Anglo-Protestants in academia — rose to its peak of influence in America. The U.S. Congress used it as a pretext to curtail immigration from Eastern Europe (Jews) and Southern Europe (Italians) by 87 percent beginning in 1924. The U.S. Department of State Office of the Historian recorded that the purpose of the Immigration Act of 1924 was “to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity.”

Nazi Germany would take and run with eugenics “research” developed in the United States. Because of the 1924 immigrant restrictions established in the U.S., and with quotas that weren’t even met, the Jews of Eastern and Central Europe were trapped in the Holocaust.

“The late 19th and early decades of the 20th century saw a steady stream of warnings by scientists, policymakers, and the popular press that ‘mongrelization’ of the Nordic and Anglo-Saxon race — the real Americans — by inferior European races (as well as by inferior non-European ones) was destroying the fabric of the nation,” Karen Brodkin wrote in How Jews Became White Folks & What That Says About Race in America (1998). She added that for Jews, “this picture radically changed after World War II,” when they were more generally accepted as “model middle-class White suburban citizens.”

Two plats in Montgomery County carried racial restrictions in 1927. The Wellmeiers Oakwood Plat in Dayton reads, “No lot or residence building on this plat shall be conveyed, leased, rented or occupied by persons other than of the White Race,” language put into place by Wellmeiers Brothers Realty Company. The Third Section of McKnights East Oakwood Plat, then in Van Buren Township (now Dayton), employed the same restrictive language as the first. The second platted section didn’t include racial restrictions.

Another two plats in Van Buren Township in 1928 included racial restrictions. Both read: “Each grantee of a lot or lots on this plat — for himself, his heirs, executors, administrators, and assigns agree that he will not sell, assign to or create a lien by mortgage or otherwise in favor of any person of any but the Caucasian race or blood; that no person of any other race or blood shall become a purchaser or assignee or become entitled to the possession thereof…”

One of those from 1928, Golf Club Estates Plat, is where my family lives. Signing on to the platting with the plat owner in 1928 was the American Loan and Savings Association.

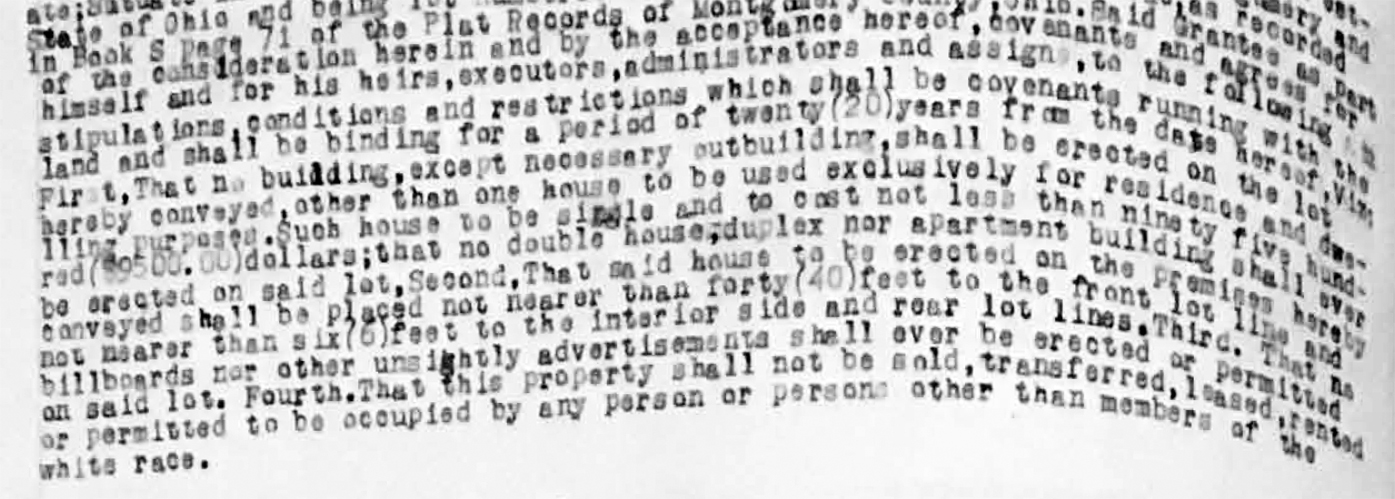

In Oakwood, investors and developers didn’t place racial restrictions on residential real estate at the plat level; they put them at the deed level. This was because the U.S. Supreme Court had struck down racial zoning ordinances in 1917 (Buchanan v. Warley) but upheld the legal right of property owners to enforce racially restrictive covenants in 1926 (Corrigan v. Buckley).

As Richard Rothstein points out in The Color Of Law: A Forgotten History of How Our Government Segregated America (2017), many border and Southern cities simply ignored the Buchanan decision.

Those looking for a more airtight legal procedure would have opted to place racial restrictions at the deed level.

At the beginning of this year, Tina S. Ratcliff, Montgomery County Records and Information manager, and Amy Czubak, a technician with Montgomery County Records Center and Archives, began to search for deeds with racial restrictions in Oakwood for this article. With Ratcliff’s guidance, Czubak found 10 examples.

“The plats we included are from 1872 to 1937,” Czubak said of the search. “There are only eight plats that were created pre-flood and none of them had racial restrictions.”

She added that she and Ratcliff were “95 percent sure” they’ve looked at deeds in all of Oakwood’s plats for that time frame. She surveyed 68 plats in total. Czubak looked at the restrictions on the first deed for each plat.

“I don’t think that this is in every single plat in Oakwood,” she said. “It’s 1924 to 1933 where you get this big influx. It wasn’t all of Oakwood. It seems like it was almost a little corner of Oakwood that was just trying to keep everybody out that wasn’t considered some sort of Caucasian.”

Czubak described some of the deeds as “quite extraordinary.”

“There are a few that specifically mention no Chinese, Japanese, or Negroes, and one that specifically states the property cannot be leased, rented, or sold to anyone of Ethiopian descent,” she said.

In 1924, the seller of a lot in the Anna M. Neibel Plat in Van Buren Township included in the deed that “said premises shall not be sold, transferred, leased or rented to any person of Negro descent.” This plat was annexed into Oakwood in 1926.

The Stomps Realty Co. included racial restrictions at the deed level for three lots it sold in 1925 within the Oakwood View Plat, also located in Van Buren Township. This deed specified “that none of this property shall be sold, leased or rented to anyone of African descent.” This plat was also part of the 1926 annexation into Oakwood.

And the seller of a lot in the Far Hills East Plat in Van Buren Township — another plat that would be annexed into Oakwood in 1926 — included in the 1925 sales deed that “said premises shall not be sold, transferred, leased or rented to any person or persons not of the Caucasian race.”

The first known racial deed restriction that originated in Oakwood dates to Jan. 12, 1928 and a lot in the Far Hills Estate First Edition Plat. The deed states that “No persons of Ethiopian Blood shall be permitted to purchase, lease or occupy any lot in this subdivision.”

Only one day later, the deed for the sale of a lot in the Mahrt Estate Plat in Oakwood included the restriction “That this property shall not be sold, transferred, leased, rented or permitted to be occupied by any person or persons other than members of the white race.”

Restrictions in 1929 to five lots in the Neibel Park Addition Plat in Oakwood indicate on the deed that “said premises shall not be transferred, leased or rented to any person or persons not of the Caucasian race.”

The City National Bank Trust Company of Dayton, acting as trustee, in 1929 sold one and a half lots in the Elizabeth Gardens Plat in Oakwood and one lot on the plat of the Village of Oakwood, with a restriction on the Elizabeth Gardens lots that “at no time shall any of the land…or any building erected thereon be occupied by any person of negro, Chinese or Japanese extraction; but this prohibition is not intended to include or prevent occupancy by such person or persons as domestic servants or while employed in or about the premises by the owner or occupant of any land included in said plat.”

The Caldwell and Taylor Corporation purchased three lots in the Mary Knoll Plat in Oakwood in 1931; they included the restriction, “Said premises shall not be sold, transferred, leased or rented to any person or persons not of the Caucasian Race.”

The largest and latest of Czubak’s finds dates to 1933. The same family that sold a lot in the Anna M. Neibel Plat (1924) and five lots in the Neibel Park Addition Plat (1929) sold 36 lots in the Far Hills East Plat in Oakwood with the restriction that “Said premises shall not be sold, transferred, leased or rented to any person or persons not of the Caucasian Race.”

Czubak said that overall, there aren’t that many deeds with racial restrictions in Montgomery County.

“I still get surprised when I come across one,” she said. “It’s not so commonplace that when I open up a deed all I think of is, there’s going to be another one. There’s no specific place or area in Dayton. It’s spread out.”

Though she adds: “Ten deeds is a pretty large amount all for one little village at the time.”

An era of antisemitism

Until our own era of Pittsburgh, Poway, Jersey City, and Monsey, the 1920s and ‘30s marked the most antisemitic period in United States history. In 1920, Henry Ford attempted to further mainstream Jew-hatred through his Dearborn Independent newspaper, which he also distributed at all Ford dealerships. Ford had the most virulent antisemitic articles from his newspaper compiled and published in four volumes for his anthology series, The International Jew.

The Second Ku Klux Klan — established in 1915 atop Stone Mountain, Ga. — arrived in Dayton on Monday, Aug. 15, 1921, according to an article in the Dayton Daily News.

“Secret but impressive ceremonies are said to have marked the meeting on Monday night of the Klan in Timmer’s woods, along the Lebanon Pike (now Far Hills Avenue), south of Dayton, when seven new members were inducted into the hooded order,” the Dayton Daily News reported Aug. 19, 1921. “Membership of the organization Friday was said to number about 40, many of whom are prominent citizens of Dayton. Their names have not been made public.”

The article continued: “It was reported Friday the local Ku Klux Klan has been formed by a local manufacturer and organizers from Cincinnati and Atlanta,” and that “the manufacturer, who is said to head the Klan here, is said to be a resident of Oakwood.”

The Daily News also reported that the Klan distributed printed cards in Dayton bearing its principles. Among those were: “Shielding the chastity of your pure womanhood…eternal maintenance of white supremacy; upholding and preservation from tyrannical oppression from any source whatsoever, of those sacred constitutional rights and privileges of a free-born Caucasian race of people, so wisely enacted by the founders of our constitution.”

By 1924, Dayton’s Klan had at least 15,000 members in Dayton, according to University of Dayton Prof. Bill Trollinger, an authority on the Klan in Ohio, who teaches history and religion courses.

The Klan’s targets, here as elsewhere, were African Americans, Catholics, and Jews. The Klan burned crosses in neighborhoods where their targets lived, including — as documented in the Dayton Daily News — one in March 1923 on the Dover Street hill in Dayton’s East End Jewish neighborhood.

In August 1923, the Dayton Daily reported that “approximately 20,000 members of the Ku Klux Klan assembled at Forest Park…said to be the largest meeting of the organization ever held in the city.”

But this doesn’t account for how Jews were unable to move to Oakwood in the years immediately after the Great Flood of 1913.

The absence of racial restrictions on plats or deeds in Montgomery County before 1924 comes as no surprise to Janet Bednarek, a professor and former chair of the history department at the University of Dayton.

“Deed restrictions are an old tool, but before the 20th century (were) used primarily to try to control ‘noxious’ uses — slaughterhouses, tanneries, etc.,” Bednarek, who specializes in urban history, explained. “It was only in the 20th century — largely in the wake of the mass immigration of the late 19th century and, even more so, the Great Migration of African Americans — that they were used to try to control the race/ethnicity of urban/suburban neighborhoods.

“The 1920s seems to be the decade that these became widely used. Oakwood essentially was created to deliberately separate its residents from the city of Dayton. Undoubtedly the residents did not want any number of ‘undesirables’ to ‘infiltrate’ their community.”

“Likely they were more unwritten,” Bednarek said of racial restrictions in Oakwood before 1924. “Most people have a sense of the ‘social geography’ of their cities — where they are welcome or not. Realtors and banks would be aware of this social geography as well. There probably weren’t any written restrictions on African Americans or on certain ethnic groups (Poles, Hungarians, etc.) common in Dayton. Further, most servants at this time were still White, so people in Oakwood would not be concerned about the race of live-in servants yet either — as they would be once more African Americans became servants in homes in the 1920s following immigration restrictions.”

She also pointed out that home ownership wasn’t yet the mass phenomenon it would be after World War II.

“Not even a majority of the middle class owned their own home,” Bednarek said. “It was a very expensive proposition. Given Oakwood’s origins as an NCR/corporate enclave, the makeup of the population who could afford to move there in the first place was fairly restrictive to begin with.”

Economic restrictions found on plats in Oakwood beginning in the 1920s excluded those of lesser means, many of whom were not White or considered White. Those restrictions often specified that only a single home could be built on a lot, and that the home would have to be valued at least at a certain price.

Bednarek explained why it lines up that 1924 was the first year racial restrictions appeared on deeds in Montgomery County. The reason, she said, is explained in a book published this year, Segregating the Suburbs: Developers and the Business of Exclusionary Housing, 1890-1960 by Paige Glotzer.

A chapter details how developers spread information about how to use covenants to restrict suburban developments in the United States.

“One key player was the Roland Park Company of Baltimore,” Bednarek said. The company, which had developed restrictive racial covenants in the 1890s, began to disseminate information on how to use such covenants by 1913.

“Initially, the dissemination mostly involved key members of the Roland Park Company talking to the few other big suburban developers in the U.S.,” Bednarek said. “However, the company was also a key member of the National Association of Real Estate Boards. It turned out that NAREB became the vehicle used to disseminate information on covenants more widely. The author of the book states that the 1920s was the key decade in which the idea of covenants spread nationally as a result of the work of the NAREB.”

The NAREB, Bednarek said, issued a publication in 1923 that included this information.

“So why 1924? That might be when the information of how to use the covenants to restrict suburbs made it to Oakwood’s realtors,” she said.

The birth of redlining

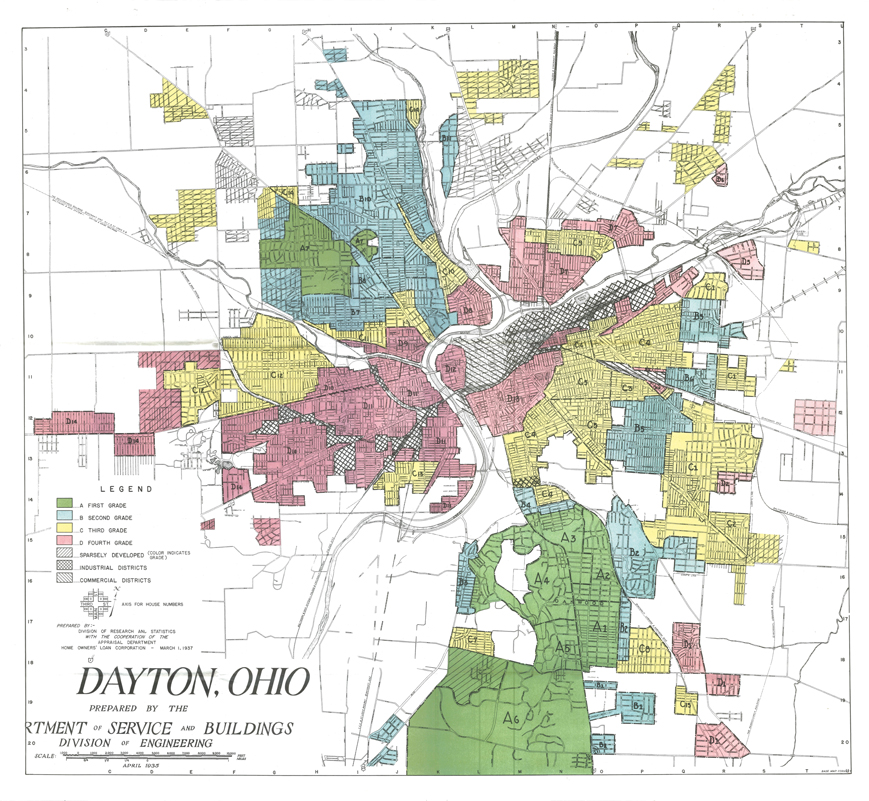

Bednarek also pointed The Observer to the Home Owners’ Loan Corporation Residential Security Map of Dayton in 1937.

President Franklin D. Roosevelt established HOLC in June 1933 with congressional approval. Its aim was to refinance mortgages in default as well as to prevent future foreclosures at a time when home ownership was still not within the reach of most Americans.

But HOLC also created the racial inequity of “redlining.” In 1935, the Federal Home Loan Bank Board had HOLC draw up “residential security maps” for 239 cities across the United States.

The maps color-coded each city’s neighborhoods and suburbs based on the security and risk assessments of real estate investments in those locations. Each color represented an investment grade.

The stated purpose of the maps was to “graphically reflect the trend of desirability in neighborhoods from a residential viewpoint.” The less desirability, the less likely the federal government would be to provide loan insurance to government-approved lenders. Factors HOLC considered in its assessments included “social status of the population.”

Along with HOLC field agents, each local map was prepared in collaboration with members of the city’s real estate board. This was the case in Dayton.

Grade A classifications, colored green, were considered the best real estate investments in a city. At the very bottom were Grade D areas, considered the most risky in which to grant mortgages.

Grade D areas were colored red. One of the great risk factors HOLC assigned to suburbs or neighborhoods was the amount of “infiltration” of “undesirables,” essentially those not considered White, and the poorest of the White population.

Redlining perpetuated the difficulties of those in the African American community to secure reasonable mortgage terms, if they could secure mortgages at all. It kept them in housing that would become overcrowded, substandard, and ghettoized in the neighborhoods where they were allowed to live.

Dayton’s 1937 HOLC map gives a snapshot of the racial restrictions in place across the Dayton area when redlining had just begun, particularly through the details listed on HOLC area description forms for each location.

All the forms included lines for agents to fill out for favorable and detrimental influences, as well as percentages of foreign born, “Negro,” “infiltration of,” and “relief families.”

Only seven area locations achieved Grade A classifications as part of the 1937 Dayton map; five of them comprised sections of Oakwood.

The five Oakwood area description forms essentially read the same. Always listed on the lines for favorable influences was “restricted” or “highly restricted.” On each Grade A form for Oakwood, there were no listings of foreign born, “Negro,” “infiltration of” or “relief families.”

The sixth Grade A area listed was in Van Buren Township, south of Oakwood. The word “restricted” didn’t appear in the area description, though neither did any foreign born, “Negro,” “infiltration of” or “relief families.”

Another “highly restricted” area, though with a Grade B, was the section straddling Dayton and Oakwood, close to the NCR plant.

Only one other neighborhood received a Grade A ranking in the Dayton area for 1937, and it was listed as “highly restricted.” It may surprise Jews in our community to learn that it was Upper Dayton View.

A 1924 deed for a lot sold by the Schwind Realty Company in the Upper Dayton View Development Company Plat, for example, carried the restriction “That this property shall not be sold, transferred, leased, rented, or permitted to be occupied by any person or persons other than members of the white race.”

By 1937, Dayton’s Jewish community had already migrated from the East End; they settled in Lower Dayton View, in two areas. Twenty percent of residents in the area just south of Upper Dayton View were listed as Italian and Jewish on the lines “foreign born” and “infiltration of.” This area held a Grade B designation, comprising single and double homes in which 40 percent were homeowners.

Just south of that area, still in Lower Dayton View, was another neighborhood where Jews lived, bearing a Grade C-. The form listed this location’s inhabitants as 80 percent “Russian Jewish, German-Polish,” with an “infiltration of foreign-Jewish…centering in this area.”

Out of a total of 46 areas on the 1937 Dayton HOLC map, another eight areas were listed as restricted: four more in Van Buren Township, three more in Dayton, and one straddling Dayton and Madison Township.

Exceptions to the rules

Three Jewish families did live in Oakwood when they weren’t supposed to.

The first was women’s clothing merchant Joseph Thal, his wife, Pearl, and their children. Joseph Thal was born in Dayton in 1886 and Pearl Thal in 1889 in Columbus, both to parents from Galicia (between Central and Eastern Europe).

The Thals show up living in Oakwood at 825 Far Hills Ave. in the 1918 Williams’ Dayton City Directory. Their son, Norman, graduated from the new Oakwood High School. But the family moved to 1116 Harvard Blvd. in Lower Dayton View by the time the 1926 city directory was in print.

Optometrist Joseph T. Cline, his wife, Harriette, and their children were first listed as living at 82 E. Dixon Ave. in Oakwood in the 1923 city directory. Cline was born in Wales in 1893 and raised in Birmingham, England. His wife was born in 1893 in Pennsylvania to parents from Hungary and Germany. Joseph T. Cline arrived in the United States in 1914. A year later, he worked in Elder-Johnson department store’s optical department. In 1917, he opened his own practice in Downtown Dayton.

Cline became John Patterson’s optometrist.

In his memoirs, Cline described Patterson as “An anomaly tome, a gentle, good-natured person, charitable and considerate of others, yet ruthless in his treatment of competitors,” adding that “he was extremely harsh with employees he deemed to be inefficient. He could not tolerate ‘yes men’ and showed appreciation of those employees who stood up to him.”

Cline wrote that Patterson’s valet, “Roberts,” brought his young son to see him for an eye exam. The optometrist fitted Roberts’ son with glasses and the boy did much better at school.

The valet convinced Patterson to consult Cline.

“Roberts informed me that his employer had suffered for years with headaches which his physician insisted was due to eye strain,” Cline wrote. “Patterson constantly visited ophthalmologists in the U.S. and Europe who had been recommended to him, but he still suffered with severe headaches. Roberts brought him to me for an eye examination. It immediately was evident that his glasses could be the cause of the headaches.”

Cline wrote that he was able to correct Patterson’s prescription and another problem that was causing him headaches.

“He had a habit of pulling his glasses off his nose and pounding them in his fist, to emphasize a point. I insisted on prescribing rigid spectacles that could not easily get out of alignment. He demurred and said, ‘Make the lenses and put them into one of my old nose-pieces.’”

Cline said he angrily told him, “Mr. Patterson, I would take your advice in selecting a cash register for my needs, and I expect you to take my advice as to eyeglasses. Either you will do so, or you may look for another eye-examiner.”

At this, Cline reported that Patterson burst into laughter and said, “Why did not other eye-men talk to me like that? Go ahead and do it your way.”

After wearing his new glasses for a few days, Patterson dropped in to express his satisfaction and selected 14 different styles of frames, two of each kind, for a total of 28 pairs.

“From then on,” Cline wrote, “there was hardly a day without some elderly person, one of his employees, or some hobo he picked up on the street, presenting one of Patterson’s cards authorizing an eye-examination and glasses to be charged to him. He suggested that I establish an office at his factory and examine the eyes of all of the thousands of his employees, but I was too busy with my regular practice.”

After the Clines moved to Oakwood — during the last year of Patterson’s life and not far from his estate — Patterson frequently asked his optometrist to come to his home with optical pliers and adjust his glasses. Patterson continued pounding his glasses on a table to emphasize a point. At times, Cline wrote that he found all 28 pairs of Patterson’s glasses required alignment.

“I spent many hours in discussion with him but conversation always got back to cash registers,” Cline wrote. “No person before or since has done so much for the city of Dayton than Patterson.”

The Cline family lived in Oakwood for 17 years; their children went to school from kindergarten through high school there. Harriette and Joseph Cline then moved to 1053 Cumberland Ave., on the only non-restricted block of that street in Lower Dayton View.

His last word about Oakwood in his memoirs, “A splendid place to raise youngsters.”

Another Jewish family that lived in Oakwood early on was the Kohnops. Max Kohnop and his wife, Minnie, were first listed as living at 236 Monterey Ave. in the 1927 city directory. At the time, he was assistant city editor at the Dayton Daily News and the local correspondent for Associated Press.

Born in Cincinnati in 1898 to parents who had emigrated from the Russian Empire, Kohnop had moved to Dayton in 1922 with Minnie when the Dayton Daily News hired him away from the Cincinnati Enquirer.

From 1939 to 1964, he served as Sunday editor of the Dayton Daily News. And from 1934 to 1976, Kohnop was president of Oakwood’s Wright Library board and served on the board until 1981. He was known as the Father of the Wright Library.

Kohnop brought to fruition Oakwood’s decades-old dream of its own library building. He guided the library through its greatest periods of growth, when its levy was passed in 1938 and the new building opened, and through expansions in 1964 and 1972.

Because Kohnop served as president of the Oakwood library board, he became one of very few to get as close as anyone could to extremely-guarded introvert and Oakwood resident Orville Wright. Kohnop already knew Wright from the days when he covered aviation.

When a vacancy came open on the library board around 1937-38, someone suggested Orville Wright for the position. It was Kohnop who called Wright and asked him to join the board. Wright agreed to serve as vice president, with two conditions: that he would never be quoted in the newspaper, everything he said would be off the record, and that Wright would never have to preside over a meeting.

Sandy Senser of Columbus, granddaughter of Minnie and Max Kohnop, doesn’t recall them talking about why they moved to Oakwood or about discrimination they may have faced there.

“They kept kosher, they kept to themselves,” Senser said in a previous interview with The Observer. “They were neighborly, they had good neighbors, but you just didn’t make a big deal about being Jewish. They would eat out, but they would only eat fish. I don’t recall going to shul with them, partly because Grandpa worked on Saturday, working on the Sunday edition.

“He used to come home at 2 in the morning or something like that after the paper was put to bed. She (Minnie) always lit Shabbos candles, we celebrated the holidays.”

The Thals, Clines, and Kohnops were active in the general and Jewish communities in very public ways. They were also all members of Dayton’s Reform Jewish congregation, B’nai Yeshurun.

Patterson & Rabbi Lefkowitz

In the public square and for the good of the Dayton community as a whole, Patterson worked with Jewish leaders. His closest Jewish relationship seems to have been with Rabbi David Lefkowitz, who eulogized him from Dallas in 1922.

Born in Hungary and orphaned in New York, Lefkowitz served Dayton’s B’nai Yeshurun from 1900 to 1920. He was a remarkable leader and social justice champion in Dayton’s Jewish and general communities. He absorbed German Jewish Reform values at the Hebrew Orphan Asylum in New York and with Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise at Hebrew Union College in Cincinnati, where he was ordained.

Lefkowitz brought Jews from across Dayton together and brought the Jewish and general communities closer together, too.

The rabbi had received a bachelor of science degree at City College in New York and taught there for two years. He also studied at the Art Students’ League. Lefkowitz graduated Phi Beta Kappa from the University of Cincinnati while attending HUC. His wife, Sadie Braham, came from a family of English Jews who had immigrated to Cincinnati. They married in 1901. Together, their embrace of arts and culture charmed gentile Daytonians.

He became an active member and speaker with the Saturday Evening Club, a long-running discussion salon in Dayton.

“About 1,000 people enjoyed a genuine old German evening at the Allen School,” the Dayton Daily News reported in 1911. “Rabbi David Lefkowitz delivered an interesting address supplemented with stereopticon views of German scenes, and Mrs. Lefkowitz rendered a number of German songs.”

The Rev. Augustus Waldo Drury wrote of David Lefkowitz in his 1909 History of the City of Dayton and Montgomery County, “He does not feel any narrow racial or sectarian boundaries but is a man of broad humanitarian spirit and who has been a close student of the vital questions of the day.”

Virtually no progressive social cause went forward in Dayton without the rabbi’s leadership.

In 1907-08, Lefkowitz chaired the Dayton Citizens’ Relief Committee to assist the unemployed. In 1910, he founded the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton. He served on the first executive committee of the Dayton NAACP when it was established in 1915.

He was vice president of the Montgomery County Humane Society (which prevented cruelty to people as well as animals then), vice president of the Dayton Vacation School Association, chair of the Dayton Playground Committee, and on the educational committee of the Dayton Chamber of Commerce.

In 1917, with America’s entry into the Great War, the president of B’nai Yeshurun, Ferdinand Ach (also the Jewish Federation’s first president), served as temporary chair of Dayton’s then forming Red Cross. Ach focused on civilian relief work, along with Katharine Wright and Patterson.

When the local Red Cross asked Patterson to become its first permanent chair, Patterson declined. The committee turned to Lefkowitz to be its chair, to oversee the mobilization of volunteer committees to provide much-needed medical supplies and nursing care for U.S. soldiers in Europe.

After the war, Lefkowitz led the chapter in its transition to local services for those in need, and the comfort and welfare of returning soldiers.

It’s unlikely Ach and Lefkowitz would have received these leadership positions with the Red Cross without Patterson’s approval.

There are numerous examples of Patterson opening opportunities to the Jewish community in the public sphere.

In 1907, the Dayton Chamber of Commerce was born when Patterson demanded that Dayton establish one or he would leave the city and take NCR with him.

The chamber’s second president, from 1908 to 1911, was Bavarian-born Jew Leopold Rauh, who owned the Egry Register Company, one of Dayton’s important industries. Rauh served on Dayton’s board of education and on the commission that established Dayton’s city manager plan of government, another important project of Patterson.

At the same time as Oakwood was essentially restricted racially, Patterson made recreational amenities available elsewhere to all members of the community.

When Patterson opened his Hills and Dales Country Club over Memorial Weekend 1916, it was billed in ads in the Dayton Daily News and the Dayton Herald as open to everyone. Among the women on the reception committee for its Memorial Day and June opening were Sadie Lefkowitz, Dorothy Patterson, and Katharine Wright.

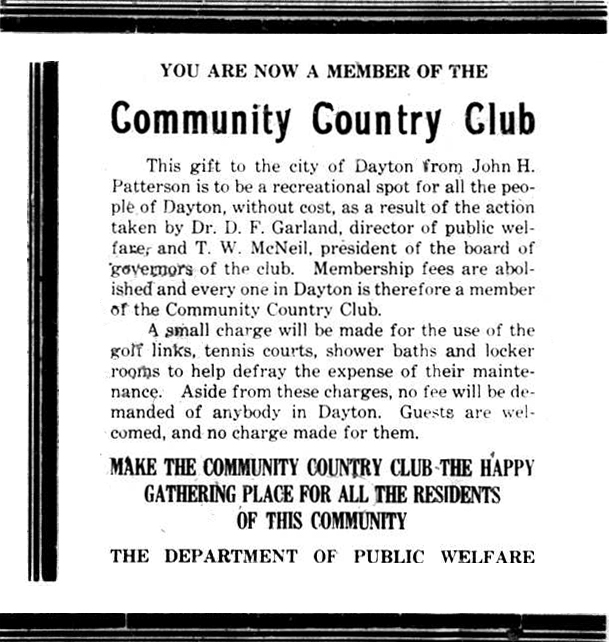

Two years later, Patterson gave the club to the city of Dayton outright, with a new name, Community Country Club. It was the first municipal country club/golf course in the nation. On the committee for the general dedication in 1918 was Rabbi David Lefkowitz.

The Community Country Club placed an ad in the May 31, 1918 issue of Dayton’s short-lived Jewish newspaper, Dayton Jewish Life: “You are now a member of the Community Country Club. This gift to the city of Dayton from John. H. Patterson is to be a recreational spot for all people of Dayton, without cost…membership fees are abolished and everyone in Dayton is therefore a member of the Community Country Club.”

The High Holy Days 1918 issue of Dayton Jewish Life included a half-page ad from NCR promoting its cash registers.

Ads for the Community Country Club in the Dayton Daily at that time also declared, “The park is designed for everyone in the city of Dayton.”

Patterson seemed to mean it. Jewish community organizations of all kinds held events and outings at the Community Country Club. Among groups to hold dances there were the Young Men’s De Hirsch (Zionist) Club and the Dayton Branch of the Jewish Welfare Board. The Catholic Federation held socials there, the Ancient Order of Hibernians celebrated Irish Day at the club, and the Clergymen’s Club — comprising “all pastors of Hebrew, Catholic and Protestant churches” and with Lefkowitz on the Clergymen’s Club committee — met there as well.

The Salvation Army held its “annual outing for the poor children and mothers of the city” at the club, Jewish-owned Traxler’s department store closed for business and held its annual employee outing there, and Jewish-owned Metropolitan Store held promotional picnics there for all boys who were members of its Metropolitan Jr. Club.

On May 29, 1921, the Community Country Club dedicated its Oak Tree Memorial Grove “in honor of the Montgomery County men who died in the world war” and presented the grove to the city of Dayton.

Leading the presentation to the city was Joseph T. Cline, Patterson’s eye doctor. Cline unveiled the stone with the honor roll of names.

“The main patriotic address will be given by Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg,” the Dayton Daily News reported of the rabbi who took over at B’nai Yeshurun in 1920 after Lefkowitz’s departure.

Documentation confirms that African Americans were able to use the club, although reluctantly on the part of the Dayton Department of Public Welfare, which oversaw the club for the city of Dayton.

An item in the July 26, 1918 issue of The Dayton Forum, the local African American weekly newspaper, related that Dr. L.H. Cox and the St. Margaret’s Men’s Club “were to be commended” for securing Hills and Dales park for an outing Aug. 9.

“Although this park was given by John H. Patterson to all the people of Dayton, a committee of colored men was recently refused use of the same,” The Forum article continued. “Dr. Cox went to the ‘Powers that Be,’ where it was admitted that the park is for all the people, and colored people can secure permission to use the buildings whenever a date is open. Thus we should contend for our rights and not be continually pushed aside.”

An article in the Sept. 4, 1919 Dayton Daily News mentions a “colored dance” at the Community Country Club. But it’s not known if African Americans were segregated to certain times and locations at the club. A Dayton Daily classified ad of July 10, 1918 lists the club as seeking a “Competent Cook, White woman.”

Successful local Jews, restricted from the Dayton area’s three private country clubs, still established their own, Meadowbrook Country Club on Salem Pike, in 1924. It opened the next year. Its first president was Egry Register President Milton Stern, and its leadership comprised the next generation of mainly German Jews who had established the Standard Club in 1883. Meadowbrook was its successor.

In 1919, Patterson established the East Oakwood Club, now the Oakwood Community Center. He opened it as a nonprofit to serve as an affordable social club for nearby Oakwood residents. There were dances on Saturdays for teenagers and dinners on Tuesdays for adults. According to an oral history, the dinners were prepared and served by “a donated domestic servant, Georgia, and her husband, John.”

An item in the May 12, 1921 Dayton Daily News indicates that the Council of Jewish Women Annual Meeting and Luncheon was held at the East Oakwood Club, with honored guests Rabbi and Mrs. Samuel Mayerberg and Rabbi and Mrs. Lefkowitz, returning for a visit from Dallas.

Patterson the Anglophile

There’s no evidence to suggest John Patterson was personal friends with anyone in Dayton’s Jewish community. But there’s ample evidence that he built relationships of respect and trust with such Jewish leaders as Rabbi David Lefkowitz and Joseph T. Cline. The two were affiliated with Dayton’s Reform Jewish congregation, the Jewish movement that prioritized comporting with decorum as assimilated Americans. Even so, I suspect something more was in play with Patterson’s connections to these two.

In his book Grand Eccentrics, Mark Bernstein described Patterson as an Anglophile.

“Patterson reached the wholly satisfying conclusion that England’s glory, like his own, was a consequence of moral grandeur,” Bernstein wrote. Patterson wrote that England “has been for centuries, and still remains, the great civilizer of the world. I believe that her prestige rests on the good that she is doing to the world, and I believe that our strength lies in the good we are doing in the world.”

Cline’s parents were born in England. Though Cline was born in Wales, he was raised and lived in Birmingham, England until he left for America when he was about 20.

Although Sadie Braham Lefkowitz was born in Ohio, her parents, Helen and Louis Braham, were born in England, as were their parents on both sides.

These were not Eastern European Jews whose families stopped over before continuing to America; they were acclimated to English life and culture as was at least one generation before them.

After Patterson

Oakwood remained essentially closed to diversity well past the Fair Housing Act of 1968, and that was already 20 years after the U.S. Supreme Court had outlawed restrictive covenants (Shelley v. Kraemer). Oakwood began opening up to the Jewish community in the late 1970s.

According to the U.S. Census, in 2010, 0.9 percent of Oakwood residents were African American, 0.2 percent Native American, 1.4 percent Asian, 0.6 percent from other races, and 1.6 percent from two or more races. Hispanic or Latino of any race were 1.8 percent of Oakwood’s population.

NCR would go on to hire its first-known Jewish executives in the late 1940s and early 1950s. One was engineer Marshall Mazer, hired in 1951, who became a department manager, invented carbonless copy forms, and would found his own printing and textbook publishing company in Dayton in 1964.

Another was Fred Scheuer, who had escaped Nazi Europe for Palestine. Fluent in German, French, English, Hebrew, and Arabic, Scheuer worked in the mid-1940s for Mittwoch & Sons, NCR’s dealer in Palestine.

Scheuer came to the United States in 1952 with plans to study engineering at The University of California, Berkeley. But when he arrived in New York, he first visited NCR’s International Office at Rockefeller Center for a tour. NCR staffers then arranged for him to visit Dayton.

Over a meal at Moraine Country Club, NCR’s international vice president offered Scheuer a job with NCR’s international education division.

“Point blank, straight to the face, I said, ‘Isn’t it an unwritten law not to hire Jews and Blacks at NCR?’” Scheuer told The Observer in 2018. “And he said, ‘It’s about time we change that.’”

Scheuer accepted, becoming only the second Jewish executive with NCR at that time (the other was from France and translated instruction manuals). Scheuer established NCR’s Latin American technical school in Puerto Rico in 1953-54. In 1955, he transferred to Dayton with his bride, Ruth. Scheuer worked for NCR for 43 years. He died last year.

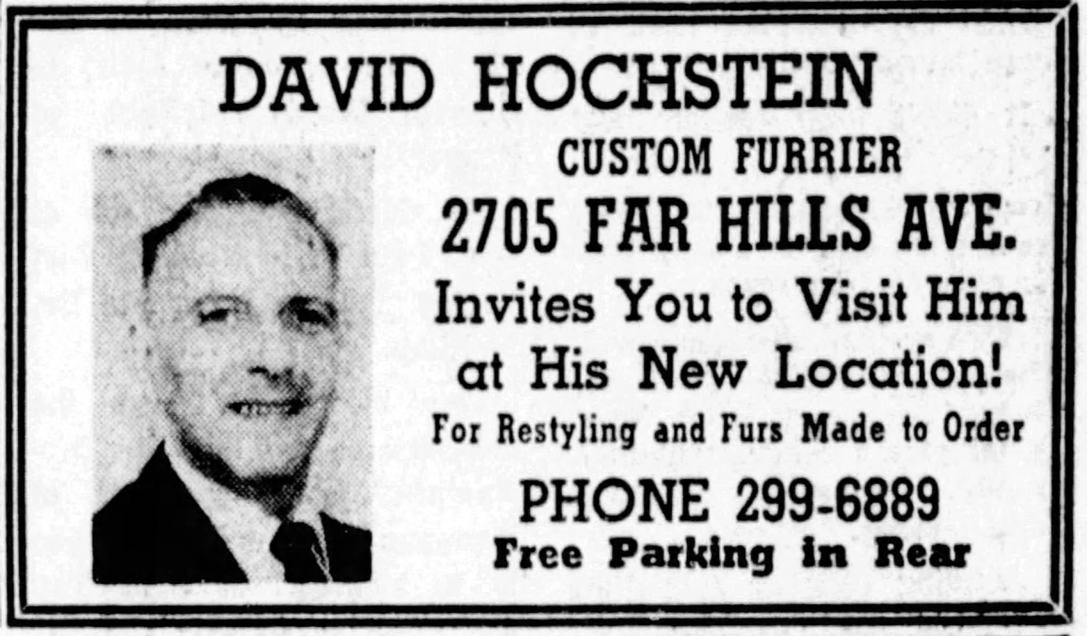

NCR executives helped the first-known Jewish business in Oakwood succeed, though some neighbors expressed their resistance.

Furrier David Hochstein learned his trade as a teenager. He escaped Nazi Germany at 15 in 1938 as part the Kindertransport rescue effort that brought some 10,000 Jewish children to live with families in England. An only child, Hochstein never saw his parents again; they perished in the Holocaust. Relatives in London secured him a six-year apprenticeship with the London Fur Company on Regent Street.

After two years in New York following the war, Hochstein opened his own fur business in 1950 in Downtown Dayton.

“He had a shop in the Arcade,” his wife, Clara, recalled. “His mazel (luck), next door was the office of the League of Women Voters. He got acquainted with them. One said, ‘Why don’t you open up a store in Oakwood?’”

Clara Hochstein said they drove around Oakwood and saw a For Lease sign in an office above 2705 Far Hills Ave. That’s where they moved their business in 1962. They kept their home in Dayton View.

“We no sooner moved (the business) in there when we got the first letter, sent through the mail,” she recalled. “It said, ‘Go back to where you came from.’”

They received two more letters. “All had the same line, ‘Go back where you came from.’ David said, ‘I’m not going to go back. We’re here, we’re going to stay here.’ I knew we weren’t welcome there.”

Hochstein Furs remained a fixture on Far Hills Avenue until David Hochstein retired and closed the business in 1988. He died two years ago.

“After a while, I guess they saw that we were nice people, and David did a good job, and they trusted him, and we became very good friends,” Clara Hochstein said. Their customers included presidents of NCR and General Motors.

“You know, we didn’t make a whole tzimmes (fuss) about it. David did his job, they appreciated what he did. I worked the front, he worked in the back at his bench. An executive from NCR, I forget his name now, he sent a letter of recommendation with his daughter, and people that came from all over the world, they sent them to us to buy their fur coats. We didn’t have to advertise. It was all word of mouth.”

When David Hochstein retired in 1988, he received a letter from the Oakwood City Council: “Your ongoing support of our community has been legendary…as you make plans, remember that you are always welcome in this community.”

Marshall Weiss, editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer, is also project director of Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, a program of the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton.

Related: Dayton’s first Jewish cemetery, John Patterson, and NCR

To read the complete August 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.

To learn more about redlining in the United States, go to Mapping Inequality, an interactive site put together by the University of Richmond, Virginia Tech, the University of Maryland, and Johns Hopkins University.