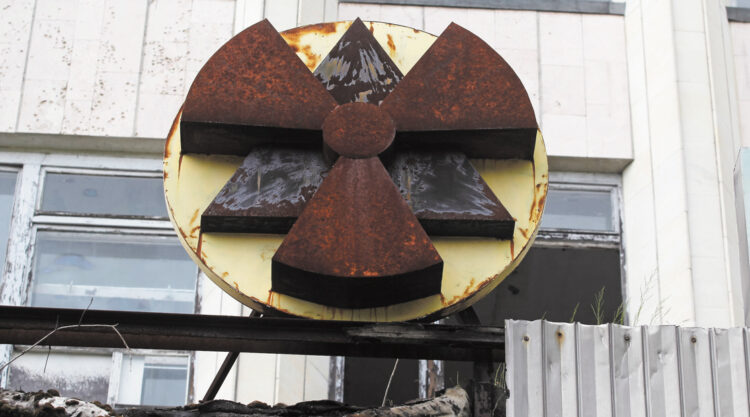

With Covid, memories of Chernobyl return

A Bisel Kisel with Masha Kisel, The Dayton Jewish Observer

I was 7 years old on April 26, 1986 when a reactor at the Chernobyl power plant exploded in the city of Pripyat, about 60 miles from Kiev, where I lived.

It was beautifully sunny and I was enjoying my first day of a military-styled fitness camp for children. We jogged through the park in matching ‘80s Soviet-era short shorts, stopping to do push-ups and jumping jacks.

As a bookish child who had already failed at ballet, this was a proud step toward becoming a model Soviet citizen.

None of us would learn of the explosion until May 4, when an announcer on the evening news program Vremia finally informed the nation about the accident.

Even then, he stressed that “bourgeois Western media” had inflated the numbers of the dead. The Soviet press lied and reported only two casualties on May 4.

Even though everything was under control and there was no reason to panic, they said, we were instructed to stay inside for two weeks with the windows closed and to wash all houseplants (this detail stuck with me).

I don’t remember being frightened. As a child, I don’t think I quite understood what it meant to enjoy the beautiful spring weather while surrounded by deadly radiation.

My parents were not patriotic enough to attend the massive May Day parade, held when the Soviet authorities already knew about the accident.

That summer, like most children in Kiev, I was “evacuated” to go live with my grandfather in Leningrad, present-day St. Petersburg.

My memories of the social response to the Chernobyl disaster come back as I struggle to make sense of this pandemic.

I watch Americans crowding on beaches and in pools since the shelter-in-place orders have been lifted even though the medical community has told us that the danger hasn’t passed.

Weeks after the explosion, people relaxed on park benches in Ukraine while hazmat suit-clad workers sprayed the grass and shrubbery around them.

Some would bring Geiger counters to the local vegetable markets and, grumbling at the high levels of radiation, would shrug and buy their produce anyway. People have to eat. In the U.S., most individuals understandably risk infection to buy groceries; those who risk infection to go bowling are a riddle, wrapped in a mystery, inside an enigma.

A fatalist attitude and gallows humor characterized the adult conversations I overheard in 1986 Kiev. Mistrust in the government, which was already common, intensified, and irreverent jokes were half-whispered between trusted friends in the kitchen.

Despite their reputation for Pollyannaish optimism, Americans are just as skilled as the Soviets at bitter sarcasm to cope with the maddening absurdity of the federal government’s response. Just spend a day on Twitter.

Many Soviets fell victim to bogus scams after Chernobyl: shamans with spells to exorcise the radiation from your food, television personalities who could charge your water with positive energy and make it safe to drink. Though no one suggested directly injecting bleach, to my knowledge.

I used to believe that Americans were more scientifically astute because the U.S. was so medically advanced, but then I see figures like Dr. Oz and Dr. Phil appear on national television to peddle snake oil cures.

Conspiracy theories and anti-vaxxers are becoming mainstream; this informational fragmentation, the erosion of faith in experts, is also a familiar sight.

Last May, my husband and I watched the HBO miniseries Chernobyl. Absorbed in the horrific spectacle of Soviet authorities sending first responders into a burning nuclear reactor, we were startled by an alert on our phones that a tornado was approaching.

We brought the kids to the basement, grateful to live in a country that had a clear plan for keeping its citizens safe when disaster strikes. Do we still live in a country like this?

We are witnessing the sovietization of America. Calling reporters “enemies of the people,” ignoring medical experts, and touting success in beating the coronavirus as deaths in America (which could have been prevented with a sane federal response) are highest in the world are a Soviet dictator’s moves.

Despite the rampant misinformation and propaganda, I am grateful to the journalists and scientists bravely keeping on.

Truthful reporting and action guided by science saved lives after the Chernobyl disaster. Targeted and threatened, scientists and reporters are saving lives in America today, as our ailing democracy struggles for breath.

Masha Kisel is a lecturer in English at the University of Dayton.

To read the complete July 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.