Einstein and pop culture: It’s all relative, says author Benyamin Cohen

By Justin Vellucci

Pittsburgh Jewish Chronicle

Jewish journalist Benyamin Cohen sees Albert Einstein everywhere. Yes, there’s the long shelf life of E=mc2. And a lot of people still know Einstein from his opposition to deploying the atomic bomb, or his theory of relativity.

But the genius thinker, who is widely considered the Western world’s first modern-day celebrity, can be seen, Cohen likes to say, in our cars, our bathrooms, and our minds.

If you like using GPS on your cell phone or getting a pizza delivered, you can thank Einstein, Cohen said.

“Einstein is one of those few characters that is universally beloved,” said Cohen, 48, of Morgantown, W.Va., who since 2021 has served as news director of the Forward. “I think people relate to him.”

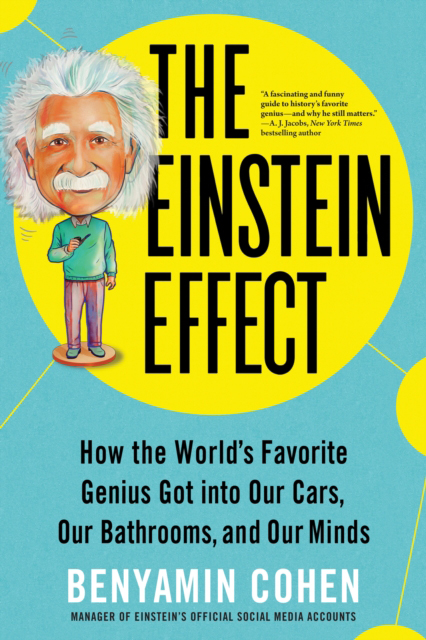

So Cohen, who manages Einstein’s official social media accounts, wrote a book about his knowledge of Einstein. The thesis of The Einstein Effect: Einstein is more relevant now than he’s ever been before.

As a teenager, Cohen didn’t know much about Einstein. Yes, there was the Nobel Prize and, of course, the crazy hair. But, while attending college at Georgia State University in Atlanta, Cohen read a book that revealed that a nimble-fingered coroner doing Einstein’s autopsy stole his brain to study what made Einstein such a modern marvel. The brain was never officially recovered.

“We were not taught that in school,” Cohen laughed. “It got me thinking: ‘What stories are there about Einstein that I don’t know?’”

For his book, Cohen traveled to an undisclosed location to meet the person who, today, keeps and studies Einstein’s brain. Cohen even held a piece of it, which is kept in Mason jars. But he’s being cagey about the specifics. The holder of Einstein’s brain needs to preserve anonymity.

In The Einstein Effect, Cohen also paints colorful stories of the German-born, Jewish thinker as a kind of cultural activist who was ahead of his time, which he thinks makes him even more relatable.

“He was the most famous person on the planet — and he wanted to use his fame to speak out against things,” Cohen said.

After fleeing persecution in Germany in 1933, Einstein campaigned against the use of the atomic bomb and helped launch the refugee resettlement group, the International Rescue Committee. It’s still around today. The list of Einstein’s activism efforts runs deep.

He fought for the persecuted Scottsboro Boys, nine Black teens accused of raping two White women in 1931. And he worked to end lynching of Black people in the American South, Cohen said. When world-famous contralto Marian Anderson, who was Black, came to perform at Princeton University but was barred from staying at the town’s Whites-only hotels, Einstein put her up at his home.

“I can escape the feeling of complicity only by speaking out,” Einstein once said.

Einstein helped groups of German Jews relocate to Mexico and to Alaska, Cohen said. In the aftermath of the Holocaust, Einstein voiced support for Zionism and the founding of a Jewish state, going so far as to travel around the U.S. raising money for Israeli independence.

Einstein’s archives — some 85,000 documents strong — are held in Israel, at Jerusalem’s Hebrew University, which Einstein helped to start. The officials behind those archives broke ground last summer on a museum dedicated to Einstein that will be the largest of its kind in the world.

Cohen typically posts to Einstein’s social media accounts 10 times a day and that dedication is reflected in followers; across platforms, 20 million people follow Albert Einstein.

Cohen, who occasionally treks the 90-minute door-to-door from Morgantown to Pittsburgh to get good kosher food, is the son of an Orthodox rabbi — and sees his own spirituality, though not observant in religious practice, in Einstein.

“He was always seeking answers,” he said, “and looking at the universe.”

“I wrote this book for other people like me,” Cohen said. “I am sure a physicist will read this book and find mistakes in it. But I want to share how Einstein is relevant today.”

The JCC Cultural Arts & Book Series presents Benyamin Cohen via Zoom, 7 p.m., Thursday, Jan. 25. The program is free. Register here.

To read the complete January 2024 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.