Pig tales

The Power of Stories Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Nearly 2,200 years ago, Antiochus IV seized the throne in the Seleucid Empire, an enormous Greek state that included Judea. To unify his kingdom, he embarked on an aggressive Hellenizing mission specifically targeted toward the Jews, outlawing the Torah, forbidding all Jewish religious practice, and forcing the consumption of pork and the sacrifice of pigs on the altar of the Holy Temple.

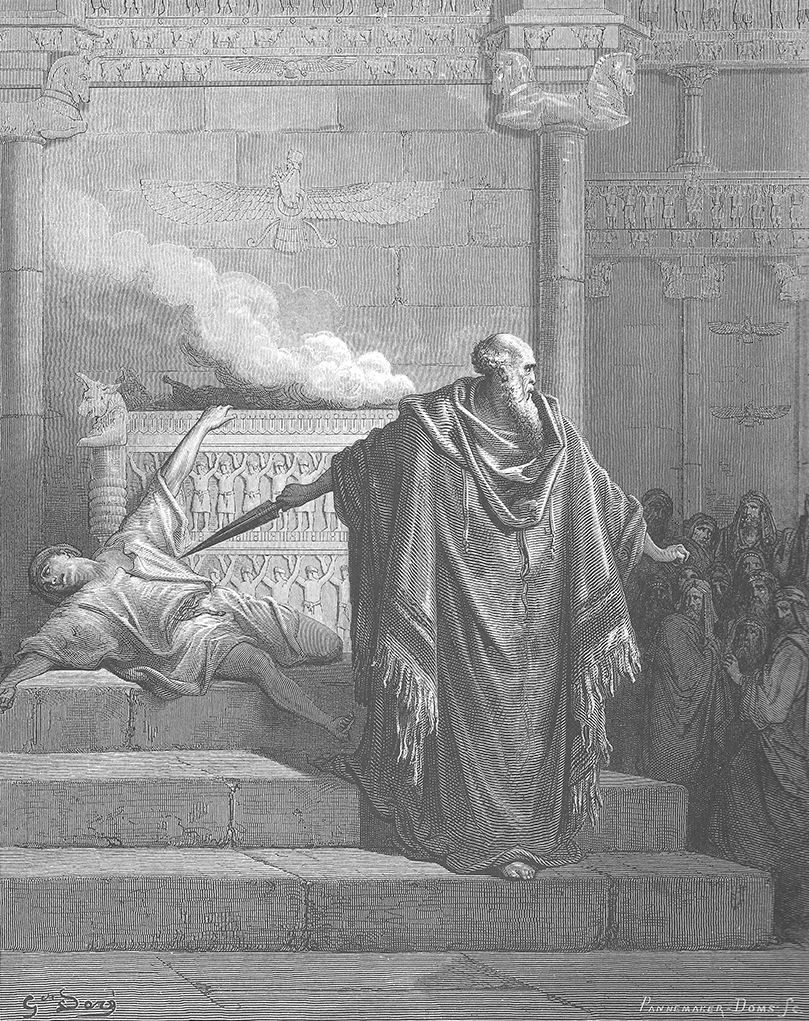

When Antiochus’ troops arrived at the town of Modiin and demanded that its Jews offer up a pig to the pagan gods (to be followed by the obligatory feast), the elderly local priest, Mattathias, replied, “Though all the nations that are under the king’s dominion obey him…I and my sons…will not hearken to the king’s words, to go from our religion.”

When another Jew stepped forward to make the sacrifice, Mattathias killed him, setting in motion the world’s first ideological religious war, that of the Maccabees.

Why the widespread Jewish aversion to pork? How did swine become symbols of Jewish oppression and antisemitism? And what lessons can we learn from the chazer, the lowly pig?

First appearing in the Bible alongside the camel and hare, the pig is one of the specified mammals prohibited as food to the Israelites, each lacking one of the characteristics of being kosher: cud chewing and cloven hooves.

“In other words,” writes food journalist Alix Wall, “pig was no more or less treyf (unkosher) than these other animals during the biblical era.”

This changed during the late Hellenistic and Roman periods, notes Prof. Jordan Rosenbaum, when Judea’s foreign rulers imported swine herding, pork as a food staple, and the pig as an essential pagan sacrificial animal.

Unsurprisingly, the significance of the pig became inflated in the Jewish mind, reflected in its “abhorrent status” both in Jewish and rabbinic sources and as a prohibited food.

Even today, the pig remains the ultimate Jewish symbol of loathsomeness, captured in colorful Yiddish colloquialisms: chazer (acting or eating like a pig, a selfish person); chazer shtahl (pigsty); and chazerai (junk, junk food).

At the same time, refusal to adopt these pig-centered pagan practices became a key marker of Jewish identity and otherness in the minds of the Jews’ adversaries.

As a consequence, the pig evolved into an antisemitic trope, starkly evident in Judensau, medieval folk and church sculptures of Jews in “obscene contact” with a sow; the epithet for Inquisition-era secret Jews, Marrano (swine); and modern antisemitic caricatures of Jews and Israel as pigs.

With the continuous negative association between pigs and food in Jewish text, history, and language, it’s inconceivable that the infant toe-wiggling rhyme, “This little piggy went to market” and the fable of the Three Little Pigs have Jewish origins. But there are Jewish pig tales with unexpectedly nourishing themes.

Pig’s feet. Although the pig doesn’t chew its cud, it does have split hooves. So why is it reviled more than other mammals that display neither cud-chewing nor split hooves?

The Midrash explains that when the swine sprawls on its side, it showcases its cloven feet as if to say, “I’m kosher!”

Outwardly kosher, but inwardly not. So too, the Midrash continues, the Roman Empire gives the appearance of holding court and pursuing justice while obscuring its underlying robbery, violence, corruption, and oppression.

Thus, pig’s feet, chazer fissel, have become synonymous with hypocrisy and superficial righteousness that doesn’t reflect inner sincerity.

Whole hog. According to Prof. Beth Alpert Nakhai, meat wasn’t a significant part of the diet in the ancient world. Living animals were much more valuable as ongoing sources of labor, transportation, milk, wool, multi-use dung, and offspring.

Pigs were the one exception, notes the author of Jewish Eating and Identity Through the Ages, David Kraemer. Providing neither food, nor fabric, nor any practical economic function while alive, pigs were simply exploited for their meat: their lives devoted to whole-hog consumption, oppressed like slaves, intended solely for death. Each portrait is an abominable life in Judaism’s worldview.

Impossible Pork. “When the vegan meat manufacturer Impossible Foods requested kosher certification for its new line of Impossible Pork, the OU balked,” Rabbi Chaim Steinmetz recounts. “Although the actual product is made of kosher ingredients, the OU found that certifying Impossible Pork as kosher was…simply impossible.”

Despite the increasing variety of “faux unkosher” products from fake bacon to imitation crab to dairy-free cheeseburgers, it seems pork carries a weight all its own.

After all, Steinmetz concludes, the pig, with its centuries-long legacy of antagonism and antisemitism, is the metaphor for something absolutely, unequivocally, and unquestionably non-kosher: chazer treyf, as unkosher as a pig.

Pig in the mud. Rabbi Mendy Kaminker tells a Chasidic story of two brothers, one a wealthy magnate and the other a God-fearing pauper. When the poor brother’s daughter was to be married, he approached his rich sibling for help with the wedding expenses.

Delighted to host his brother, the rich fellow invited him on a tour of his palatial home. After a while, however, the poor brother tired of viewing the spacious rooms, opulent furnishings, and lavish gardens and asked to cut the tour short.

Puzzled, his bigwig brother responded, “But there’s still more to see!” His poor brother replied, “There is a creature that wallows in the mud all day. If you ask it what it wants, all it can think of is, ‘More mud!’ You, too, are sunk in the mud of possessions and material pleasures, and all you want is more mud instead of focusing on the truly important things in life.”

Although rare, Jewish pig tales reveal surprising insights about culture, conduct, and character worth pondering.

Literature to share

Professor Buber and His Cats by Susan Tarcov. About to lose his bookstore home in Jerusalem, Ketem the cat decides to relocate to the book-filled home of the famous philosopher and author Martin Buber. Tarcov’s charming picture book for young readers explores Buber’s life and unique worldview from a cat’s point of view, expressed in dreamy thoughts and feline fantasy. The values of respect, relationships, communicating with God, and the surrounding world permeate the story. An engaging introduction to a significant Jewish historical figure.

The Escape Artist: The Man Who Broke Out of Auschwitz to Warn the World by Jonathan Freedland. The book opens with 19-year-old Rudolf Vrba and 26-year-old Fred Wetzler poised to escape from Auschwitz. After three days hiding in a pile of discarded wooden boards, they would be the first Jews ever to escape from the death camp. But their journey was just beginning. Freedland seamlessly weaves together memorable characters, detailed experiences, evocative descriptions, and heart-stopping suspense into an award-winning page-turner.

To read the complete June 2023 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.