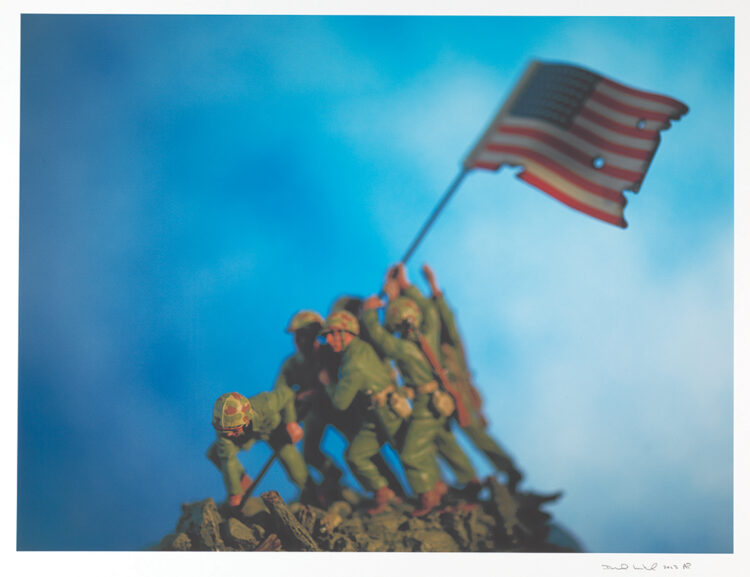

Myth & memory in photographer’s toy dioramas

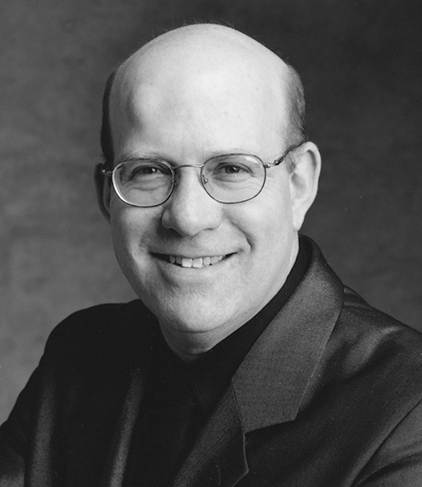

An interview with David Levinthal

By Hannah Kasper Levinson, Special To The Dayton Jewish Observer

David Levinthal is a photographer based in New York whose exhibit, American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs, opens Oct. 15 at the Dayton Art Institute. The exhibit is on tour from the Smithsonian American Art Museum.

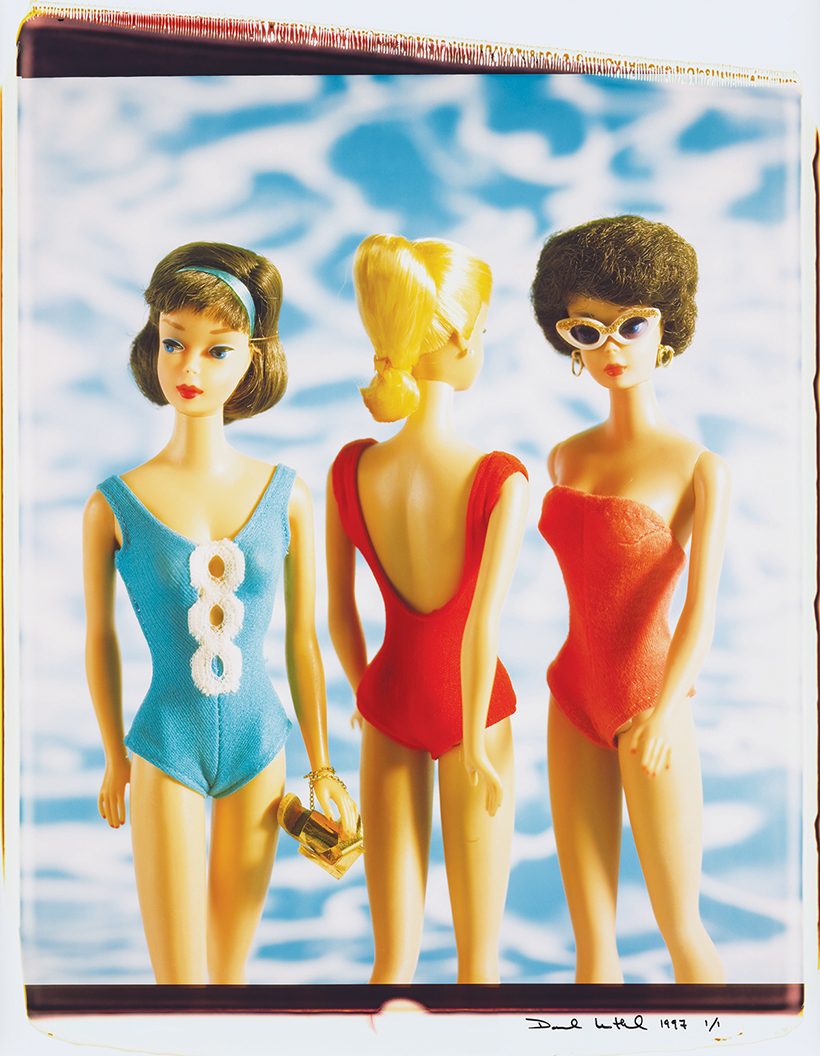

Levinthal works in series, inspired by historic events and American cultural icons. His signature style first emerged in graduate school at Yale in the 1970s. He captures familiar miniature toys — dolls and toy soldiers — set up in a diorama, with the camera very close to the subject. This creates a narrow depth of field — like looking through a peephole — giving the effect of peering into a realistic environment.

To unravel David Levinthal’s work is to question our universal fascination with miniatures. The miniature takes us back to the ancient Egyptians, who buried their dead with clay representations of everything they may have needed in the afterlife: tools, furniture, and servants all small enough to hold in one’s hand. The earliest evidence of the dollhouse, itself a miniature, was one made for a Bavarian duke in 1558.

The connection between miniature and imagination is based largely in relationship to childhood. To see detail in small things requires such attention that to experience it detaches you from the surrounding world.

The make-believe world of a child is much the same. Miniatures and childhood also bring associations of fairy tales. In Hans Christian Andersen’s Thumbelina, the protagonist is so miniscule that she experiences her own world within the real one. Like a fairy tale, the playfulness in Levinthal’s photos masks more complex themes rooted in adult subject matter.

Here, David Levinthal talks about his influences and the connections to Judaism in his work.

How did photography become your medium?

When I went to college in 1966, my intention was to be a poli-sci major and go to law school. That lasted pretty much one class. There was something at Stanford called The Free University. Anyone could teach a course on anything. Dwight, a friend who taught there, was the epitome of cool. He had really long hair and every time I saw him on campus there were beautiful women with him and I thought, “I want to be like that.” Dwight was teaching a photography class and taught me how to develop film and make a print. I just became so fascinated by it. Stanford at the time did not offer photography, which I feel was a very positive thing for me because it meant that if I wanted to do it, I had to be self-motivated.

What do you hope the viewer takes away from your work?

So much of my imagery draws upon everyone’s own visual memories, film, television, paintings. When you look at my photographs, there’s often not a lot of detail, but the images in the photograph play off of one’s own visual memory bank. It’s like you’re filling in a lot of the space and creating a story about what had happened and what is about to happen.

The collection of the Dayton Art Institute includes epic paintings depicting battle scenes, landscapes, historical figures. They make me think of your subject matter. What inspires you?

As a 13-year-old, my parents took my sister and I to Europe and I remember going to the Louvre every day and I loved the history paintings: those magnificent battles, the king on horseback in the foreground. Painting to this day is still a big influence. When I was doing the cowboys series, I referenced a lot of Remington and Russell, painters who depicted the American West. If you were making toys in the ‘30s and ‘40s, your reference was probably those painters. Figures on horseback were sculpted from a painting and made into a toy, which I then photographed. So much of my inspiration comes from film. I loved looking at the John Wayne movie The Searchers to get a sense of the background colors and tried to replicate it in my photograph.

That’s a lot of layers. Does being Jewish or your personal identity play into your work?

I think my Jewishness really impacted me when I was doing the Mein Kampf series. I would say probably most of the photographs I did in that series were related to the Holocaust, using documentary photographs as a starting point. I was in Graz, Austria for a gallery show. I found this store that had military memorabilia and a Hitler toy figure. I was talking to the owner and he proceeded to tell me about someone who had the old toy molds from the ’30s and ‘40s who was living in the Black Forest and still making these figures. I was able to get a number of the figures.

It says a lot that these toys are still being made.

I received a Guggenheim grant and a friend of mine who is a Holocaust scholar at UMass Amherst arranged for me to stay at the study center outside of Auschwitz. I was all alone in this large dormitory. I was literally right across the dirt road from Auschwitz. Auschwitz was set up almost like an exhibition, but Birkenau was just there, totally raw. There were very few people. I remember walking up the tower under which the trains came. It was about four stories high. I was up there by myself, looking down at the train tracks, and you could see people but they were so miniaturized. They almost seemed not human.

Almost like toys.

Yeah, which was a really strange feeling to have. I read a book that said at Birkenau there was a pond way at the back and that if you dip your hand into the water and pull out some mud, you’ll see bone fragments. Which turned out to be absolutely true.

Did you do that?

I did that. Walking along those train tracks and thinking, this is where people were disembarked from the cars. It’s probably the same gravel that was there. It was truly a once-in-a-lifetime experience. It was very impactful. It gave me a much better sense of a lot of the Jewish stories of that time. When I exhibited the work, I was always very conscious and hopeful that people would not be hurt or offended by my use of the toy figures. I had a number of survivors come over to tell me how touched they were by the work, and that meant so much to me. I’m using toys, I’m trying to be as passionate and creative as I can be but, it’s still toys. To hear that really made me feel great.

American Myth & Memory: David Levinthal Photographs on view Oct. 15-Jan. 15. at the Dayton Art Institute, 456 Belmonte Park N., Dayton. For more information, go to daytonartinstitute.org.

To read the complete October 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.