Holocaust exhibit at Air Force museum ready for school groups to return

Story and Photos By Marshall Weiss, The Observer

Longtime local Holocaust educator Renate Frydman has noticed an uptick in Holocaust education in schools.

“For a while, there was less teaching of it,” the Dayton Holocaust Education Committee chair says. “Now, I think, with the world the way it is, there are more teachers teaching the Holocaust than you can ever imagine.”

Her hope is that after more than two years of disruption to in-person learning because of Covid, teachers will bring their middle- and high-school students back to Prejudice & Memory: A Holocaust Exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force at Wright-Patterson Air Force Base.

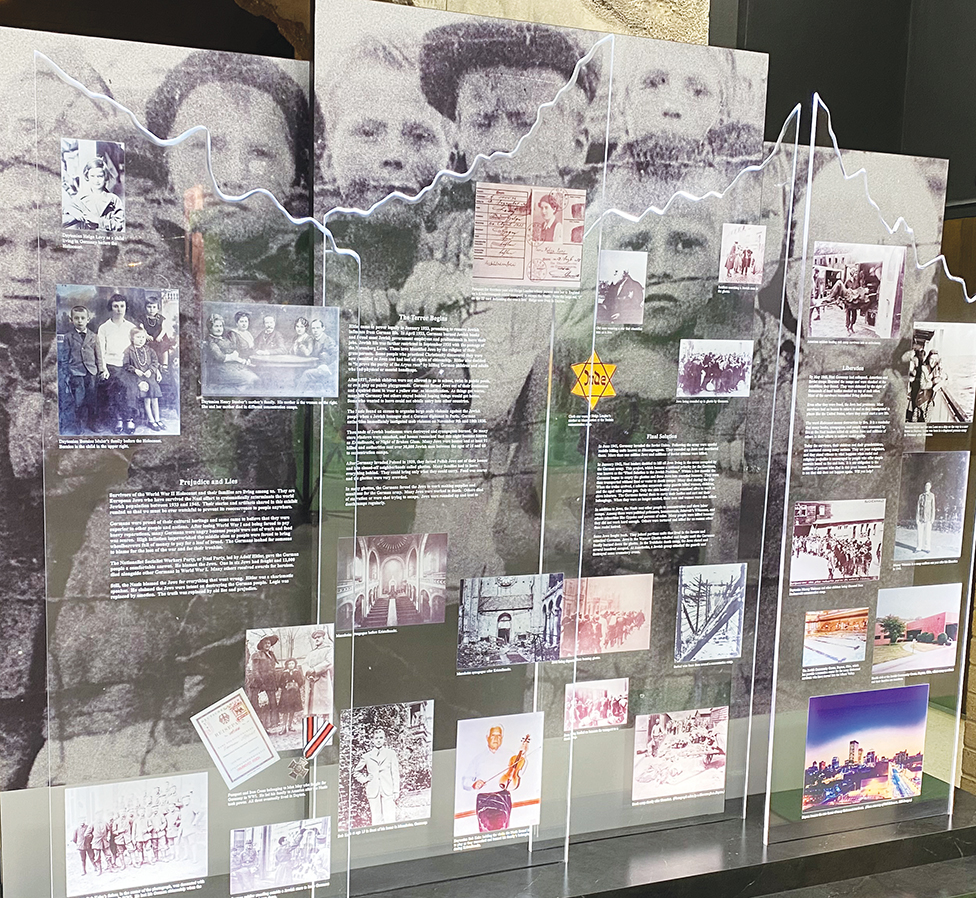

Frydman is the curator of the exhibit, which has been on permanent display at the Air Force museum since 1999. It was among the first in the United States to focus on a community’s local survivors, liberators, and rescuers.

“These are your neighbors,” one display proclaims of those featured in the exhibit. Most have since passed on. Their testimonies and artifacts keep their memory — and the lessons they taught — alive.

Museum restoration volunteer Dave London completed long-needed renovations to the exhibit at the end of June.

“There was a lot of recognition that this area was beaten up bad,” says London, a retired Air Force engineer who has volunteered in the museum’s exhibit areas for about a year and a half.

“A lot of the walls (of the exhibit) are actually made out of Styrofoam and pieces are broken off. It was not looking great. And everybody recognized that something had to be done. But the question was what.”

London tested some possible solutions on the pillars at the entrance to the exhibit; he tried various paints and coatings to see what would stand up best to the amount of traffic coming through.

“Once I found something that worked well — a couple of coats of thick sealant and the texturing and different color paints over that — I came through and did the whole display. This was my project for the good part of a month. I’ve never done anything like that before, so I’m just really happy with the way it came out.”

“I was glad to see how it looks,” Frydman adds. “And it’s solid. The lighting is also different. It’s lower now to protect the artifacts.”

Frydman and museum-trained volunteers lead school groups on tours of the exhibit, which bridges the space between the World War I and World War II galleries, with some exhibit elements incorporated into the World War II gallery.

“The way they’ve changed the flow of people since Covid, pretty much everybody who visits has to come through here,” London says. “It’s part of the normal flow.”

“It’s very personal,” Frydman says, of how visitors are drawn to elements in the exhibit. “Most people stop at one particular place that attracts them. They want to know more about it.”

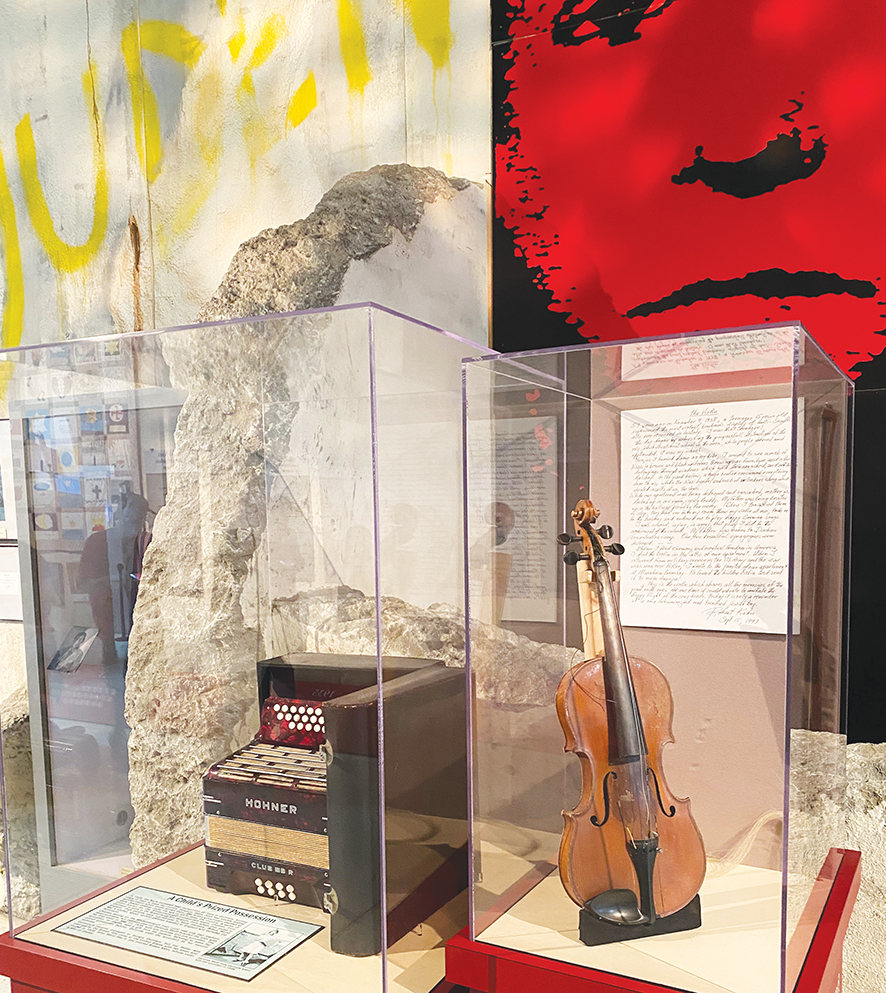

Such places include the Buchenwald concentration camp uniform of survivor Moritz Bomstein, the accordion 14-year-old Gertrude Wolff Kahn took with her when she was rescued from Nazi Germany through the Kindertransport program, and the violin her husband, Robert Kahn, was forced to play at age 15 on Kristallnacht as Nazis beat his father.

Air Force museum Education Specialist Patrick D. Hannon notes the concentration camp uniform is a rare artifact.

“Most were destroyed or disposed of,” he explains.

London points to a student-made Holocaust-themed quilt displayed on a wall in the exhibit.

“That quilt was made by my daughter’s class in junior high school,” London says. “In the top right corner, the guy who did that square, he’s now the mayor of Cincinnati.”

Frydman knows the difference each teacher can make when it comes to fighting hate. She cites the national backlash when a Tennessee school board voted to cut Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Holocaust graphic novel Maus from its middle school curriculum earlier this year.

“Teachers are often independent in their thinking,” she says. “We’re not talking politics. We’re talking in the way they think and feel. And so yes, there are certain things they know they need to adhere to, but there are also things that they want to do. And many teachers find a way to put the Holocaust in, in remarkable ways, sometimes. They believe it should be taught. And they see results.”

Over in the World War II gallery is a French railroad car constructed in 1943. Millions of Holocaust victims were herded into this kind of boxcar and sent to concentration camps. Allied prisoners of war were also transported to German POW camps in these boxcars, some even to Buchenwald concentration camp.

“According to the information at this exhibit, 168 Allied POWs were moved from Paris to the Buchenwald concentration camp in August of 1944,” Hannon explains. “Many of these POWs were aircrews that had been shot down. Those of Jewish faith were separated from the other POWs and shipped to concentration camps.”

This railcar, part of the Prejudice and Memory tour, was airlifted to the Air Force museum in 2001.

At one time, Frydman says she had 15 volunteers who led tours of Prejudice & Memory, several of them survivors. “I’ve lost a few due to illness,” she says. “But now, there are people coming up who want to be exhibit volunteers, either from the volunteer group that’s here, which is 500 or close to it, or from outside.”

In July, Frydman led the Holocaust Education Committee’s annual retreat; some participants said they’d like to become exhibit volunteers.

“All of the Holocaust exhibit volunteers have had something in their life that relates to this,” Frydman says. “We’ve had a lot of retired teachers.”

Frydman originally designed Prejudice & Memory as a mobile exhibit in 1997. For more than a year, she had collected artifacts from local survivors, liberators, and rescuers.

Prejudice & Memory had been on display at 10 sites across southwest Ohio when the late retired Maj. Gen. Charles D. Metcalf — then director of the Air Force museum — invited Frydman to display the exhibit at the Air Force museum from February through September 1999.

“About two weeks into it, Gen. Metcalf said, ‘What would you say if I told you we want it permanently?’ I almost fainted at that moment. And here it is.”

In the last full year before Covid, 2019, the museum hosted approximately 750,000 visitors. Admission to the museum is free to all.

Frydman says she and the Holocaust exhibit volunteers talk with student groups about prejudice, bullying, respect, and antisemitism.

“They think about it,” she says of the students. “With the whole atmosphere of the museum and the exhibit, being together in a place where someone tells them a story they’ve never heard, they feel the element of remembrance.”

The Holocaust Education Committee can also provide grants to schools unable to pay for transportation to the museum exhibit.

“We don’t want any school not to be able to come because they can’t pay for busses.”

Hannon notes that when Frydman shares her own story and gives tours of the exhibit, “kids that are normally rambunctious and a challenge to have focus are solemn and attentive.”

“Renate emphasizes how hate and prejudice can get out of control, and how one person can make a difference. It is probably a message that the teachers have been trying to get across to their students, but until they see the extreme consequences, it doesn’t sink in. Both teachers and students are left humbled by the experience.”

With the unknown of how new variants and subvariants of Covid will play out over the coming months, Frydman hopes for the best.

“It’s up to the schools, the districts. Are they going to allow more field trips? Now that the museum is open, they can come. Hopefully, they will come.”

To schedule student tours of Prejudice & Memory: A Holocaust Exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force, contact the museum’s education division at nationalmuseum.mut@us.af.mil or 937-255-8048. For information about transportation grants, contact Renate Frydman at rfrydman25@gmail.com.

To read the complete August 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.