Dayton’s JCC at 100

Part One: Becoming Americans

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Even a week before the Jewish Federation for Social Services completed its June 26, 1922 purchase of the house at 59 Green St. to serve as Dayton’s first Jewish Community Center, the Dayton Daily News wrote of the Jewish community’s plans for the site.

“Dayton will have a special school for the Americanization of its foreign-born Jews above the school age,” the June 18, 1922 article reported. “Detailed plans for this school have been formulated and will be announced publicly at the open meeting of the Dayton B’nai B’rith lodge Wednesday evening.”

All sessions of the school, the article continued, would be held at the new JCC, “now undergoing alterations and which will be ready for occupancy within the next two weeks.”

“With the co-operation pledged by all other Jewish organizations in the city, the B’nai B’rith will have for its objective, ‘Every foreign-born Jew in Dayton a naturalized citizen.’”

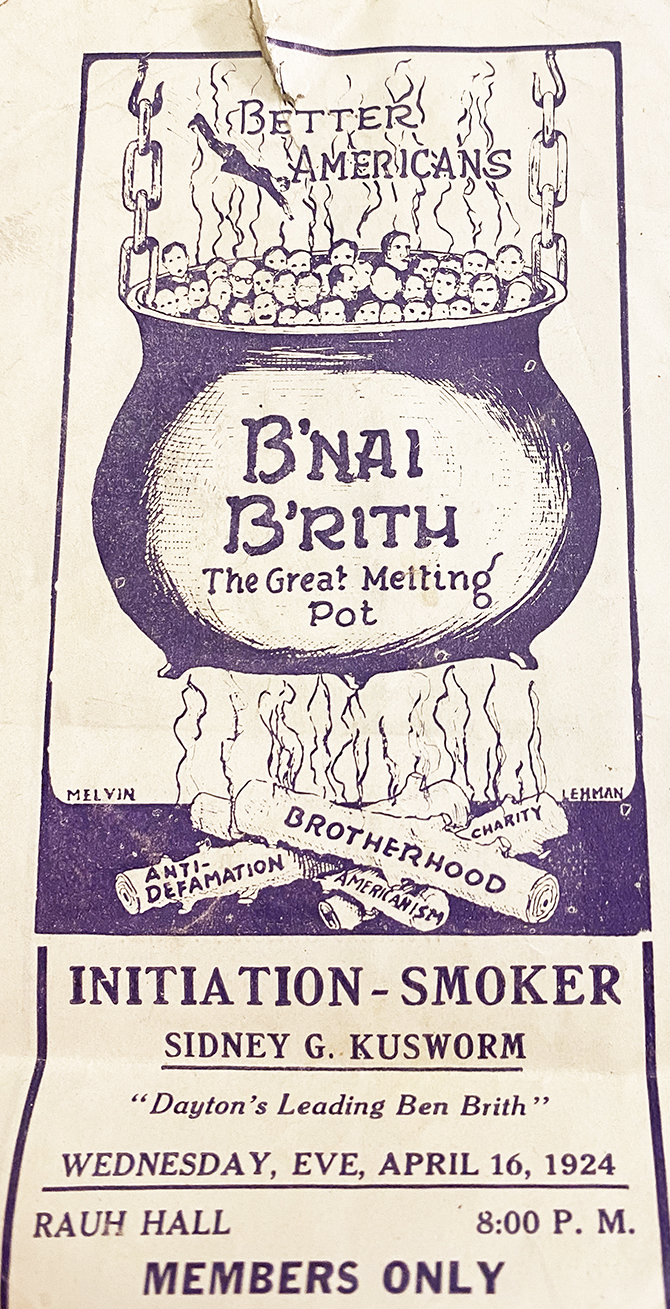

The primary purpose of Dayton’s JCC in its first decade was to Americanize Dayton’s most recent Jewish arrivals: impoverished, uneducated Jews who had fled Eastern Europe even as the gates to America were closing. The leader of this local effort was also the chair of B’nai B’rith’s new national Americanization committee, Sidney G. Kusworm Sr. The person to implement his vision over nearly two decades would be Jane G. Fisher, who dedicated her life to the new field of social work.

Volunteers from across Dayton’s Jewish congregations and myriad Jewish organizations came together at 59 Green St. — in the Eastern European Jewish neighborhood of the East End — to teach Jewish immigrants how to become self-sustaining and how to comport themselves in the Gem City of the Golden Land.

A national powerhouse

Over the eight decades since B’nai B’rith began in 1843 as a Jewish fraternal organization in New York, it had grown into a powerhouse of social service, social justice, and Jewish cultural initiatives.

B’nai B’rith founded the Anti-Defamation League in 1913 and the B’nai B’rith Youth Organization in 1925. It adopted and supported Hillel a year after the Jewish college organization’s 1923 founding. It founded and supported hospitals for Jews suffering from tuberculosis, America’s number one killer in the first decades of the 20th century. B’nai B’rith founded and supported Jewish orphanages.

And in 1921, B’nai B’rith set out to ensure Jewish acclimation to the United States.

At age 36, attorney Sidney G. Kusworm was the youngest member of the B’nai B’rith National Executive Committee in 1921. He had already served two terms as the second president of Dayton’s Jewish Federation beginning in 1913. And he had served as president of Temple Israel, the congregation of Dayton’s established German Jews, who had founded the Federation in 1910.

In the spring of 1921, the national B’nai B’rith named Kusworm the first executive director of its Americanization Department.

B’nai B’rith’s mobilization of this department was no doubt tied to the Emergency Quota Act of 1921, passed overwhelmingly by Congress and signed into law by President Warren Harding on May 19, 1921.

Though a temporary measure, the Emergency Quota Act significantly curtailed the burgeoning immigration of “undesirables” into the United States: southern and eastern Europeans (Italians and Jews).

Three years later, the Immigration Act of 1924, a permanent measure, would even further slash immigration from southern and eastern Europe by 87 percent even as the brutality Jews faced in Eastern Europe continued.

Kusworm introduced his Americanization plan to all B’nai B’rith lodges across the United States at the end of 1921:

“The B’nai B’rith intends to take an active and aggressive part in this tremendous task and the program as planned includes the teaching of English, civics, and American history to the foreign born. But most important of all is to strive with all the power we possess to inculcate the spirit of democracy in all our immigrants…It is not only a work which we owe to our co-religionists but it is also an act of patriotism to our beloved country.”

His plan called for lodge members across the United States who were lawyers to volunteer as instructors in civics and American history.

In Dayton, Temple Israel’s Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg was appointed president of B’nai B’rith’s local Americanization Committee. Kusworm and then-partner Ben Shaman were among the faculty registered to teach at the school.

They and other Jewish lawyers provided legal services at no charge to the immigrants. Jewish physicians provided the immigrants with free medical care.

Dayton’s Jewish community of approximately 5,000 people already had a reputation of caring for its own — and for its desire to become U.S. citizens.

“Dayton Jews are conspicuous among our most progressive and philanthropic citizens. Their societies reach out to all their people,” the secretary of the Dayton YWCA’s Immigration and Foreign Community Department noted in a 1917 report, Foreigners In Dayton, An Investigation.

“A visiting committee of the Young Men’s Hebrew Association conducts a class in English for 24 Jews at the Patterson School night class in English during the past year,” the report indicated. “The Jews themselves ‘rush the process of citizenship,’ and of all our immigrants, need the least stimulus toward self-improvement educationally. They are eager for the privileges which were denied them through unsympathetic governments in the old country.”

As early as 1913, when Kusworm was Federation president, he called for “immediate steps” to be taken to establish a settlement house, “to serve as a temporary place of residence for new immigrants that come to Dayton,” the Dayton Daily News reported. “Educational classes are also to be conducted for persons desiring to learn the English language, the customary studies of elementary schools, and the workings of the American government. Classes for the benefit of mothers are also to be conducted in sewing, domestic economy, and domestic science.”

The great wave of Jewish immigration from Eastern Europe, which had begun in 1881, was still on in 1913. With the outbreak of World War I in 1914, that would end, as would the local Jewish community’s ability to fund a settlement house for its newest Jewish immigrants.

The Dayton Jewish community’s highest priority beginning in 1914 was relief for the Jews of Eastern Europe: starving, attacked, and murdered while the war raged on.

Another high priority emerged for Dayton’s Jewish community with America’s entry into World War I in 1917: support for Dayton’s new Red Cross chapter — led by Temple Israel’s Rabbi David Lefkowitz — to ease the suffering of women and children in war-torn Belgium and France, to provide much-needed medical supplies and nursing care for U.S. soldiers in Europe, and then after the war, to transition to local services for those in need and the comfort and welfare of returned soldiers.

In 1918, the Jews of Dayton established a Jewish Welfare Board chapter to provide support for Jewish and non-Jewish soldiers stationed locally.

JCC precursors here: YMHA & YWHA

The same year Dayton’s Jewish Federation was established, 1910, a group of Jewish men organized Dayton’s Young Men’s Hebrew Association. Its first president would also become an early president of the Jewish Federation, A.W. Schulman. Three years later, the Dayton YMHA affiliated with the newly formed national Young Men’s Hebrew and Kindred Association, and soon after opened its Dayton headquarters at 339 W. First St. Kusworm was a member of the YMHA, which also added two women’s auxiliaries; they would form their own organization, the Young Women’s Hebrew Association, in Dayton in 1915. Kusworm’s wife, Helen, was an active volunteer with the YWHA.

At first, the purpose of the two organizations was to provide social, cultural, and physical recreation for their members. In 1914, the YMHA formed a basketball team and even announced plans to install a gym in its building.

But at the same time, they adjusted their priorities out of necessity: The YMHA opened a night school in 1914 for Jewish immigrants, in partnership with the Federation. In 1917, Dayton’s YMHA and YWHA considered opening a community house. However, they faced the same financial challenges and immediate shift in purpose as did the Federation during World War I. Ultimately, when the Jewish Federation opened the JCC in 1922, the YMHA and YWHA became clubs of the Federation and met at the JCC.

A well-used piano

Nearly a year after the JCC at 59 Green St. opened — after it had undergone renovations — it held an open house for the general public on March 14, 1923.

A few weeks later, the JCC’s executive secretary, Miriam S. Van Baalen, sent a letter to Sidney G. Kusworm:

“We have received the piano which you have presented to the community center in memory of your beloved wife, and I wish to express to you the deep appreciation we feel for a gift which carries with it memories so tender and sacred.”

Helen F. Kusworm had died in 1918 at age 29 of heart problems. She and Sid, who had one son, had only been married six years. He never remarried.

The piano would be put to good use at the center. In its first full year of operation, the JCC’s programs included the classes Folk Songs and Rhythmic Dancing with Clara Bell Marcus and Dancing with Josephine Schwarz, who with her sister, Hermene, would found the Dayton Ballet 14 years later. The center also held Saturday evening dances and was the meeting place for the Jewish Boy Scout troop.

In her report for 1923, Van Baalen explained how the JCC undertook its immigration work:

“The chairman of the Immigration Committee of the Council of Jewish Women makes the first visit when she is notified that a family or individual has arrived. She interests the family in the ways of becoming Americanized and refers them to our classes and clubs as the first process. We make additional visits urging attendance at our English classes and Mother’s Club, and progress towards American ideals and ideas has been noticeably rapid in several instances.”

Enter Jane G. Fisher

The arrival of social worker Jane G. Fisher from New York in May 1924 to serve as the JCC and Federation’s new executive secretary deepened the center’s settlement house approach to Americanizing Dayton’s Jewish immigrants, with a focus on arts and culture.

Born in Warsaw, Poland in 1885, Fisher arrived in the United States in 1896. She entered the field of social work in 1912.

The settlement house movement began in England in the 1880s as a reformist social movement, and soon came to America, most notably with Hull House, founded in 1889 by Jane Addams and Ellen Starr in Chicago, and the Henry Street Settlement House, founded in 1893 by Lillian Wald in New York.

Their aim was to bring people from all levels of society together for the common purpose of improving the conditions of the poor, empowering the poor to rise up and become self-sufficient. The field of social work sprang directly out of the settlement house movement.

Fisher first met Jane Addams in 1912 at a national conference of settlement workers in Boston. Addams invited Fisher to serve as a guest on the Hull House staff for six weeks in 1913 before Fisher began her assignment at the Newark, N.J. Settlement House.

“She proved the common humanity of us all — rich, poor, honest and crooked — and the healing effect of better living conditions,” Fisher said of Addams. “She was never afraid.”

Before arriving in Dayton, Fisher had undertaken an extensive two-year study of the immigration situation in New York while working there in child welfare.

One of her first projects here was to start a series of free outdoor summer concerts in the garden at 59 Green St., beneath two cherry trees.

“Miss Fisher maintains (and rightly) that music is a food just as bread or meat; that our souls demand music,” wrote a Dayton Daily News columnist in July 1924.

The soloist for the first concert was 16-year-old violin virtuoso Paul Katz, who would found the Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra nine years later. That same year, 1933, Fisher established the JCC Music School at 59 Green St., with Katz directing its violin department and offering individual lessons.

Hands-on learning was integral to Fisher’s approach. In 1926, she asked a college graduate who had majored in biology to dig a hole in the backyard at 59 Green St., fill it with water, stock it with fish, and teach the children how to fish.

“And we bought the poles and taught the kids to pull out the fish and then we taught them not to kill them, and to put them back in,” the graduate recalled 59 years later for a Jewish Federation oral history project facilitated by Linda Patterson.

“Whatever she said was law,” said another oral history project participant of Fisher. “Green Street also had a fund, and nobody knew who they gave to or how they gave it. If a newcomer came to town and he didn’t have any money, they would find him a house, a place to live, and buy him a horse and wagon.”

Fisher successfully kept immigrants in this country when immigration authorities sought to deport them and oversaw distribution of relief for families unable to maintain themselves.

But her overarching belief, directly in line with the settlement movement, was that social workers “can build families today and thereby help prevent poverty 10 years from now.”

The synagogue center movement

A century ago, Jewish congregations also began incorporating the community center concept into their facilities to interest a new generation of Jews in becoming and staying on as members.

Rabbi Mordecai Kaplan, who inspired the Reconstructonist movement, was among the first to include cultural and recreational activities at his synagogue, the Jewish Center on Manhattan’s Upper West Side, beginning in 1918.

As Brandeis University Prof. Jonathan Sarna writes in American Judaism, “The idea involved broadening the synagogue’s mandate to embrace a range of social, educational, and even physical fitness activities designed to turn the house of worship into a seven-day-a-week multipurpose center, a hub of Jewish life.”

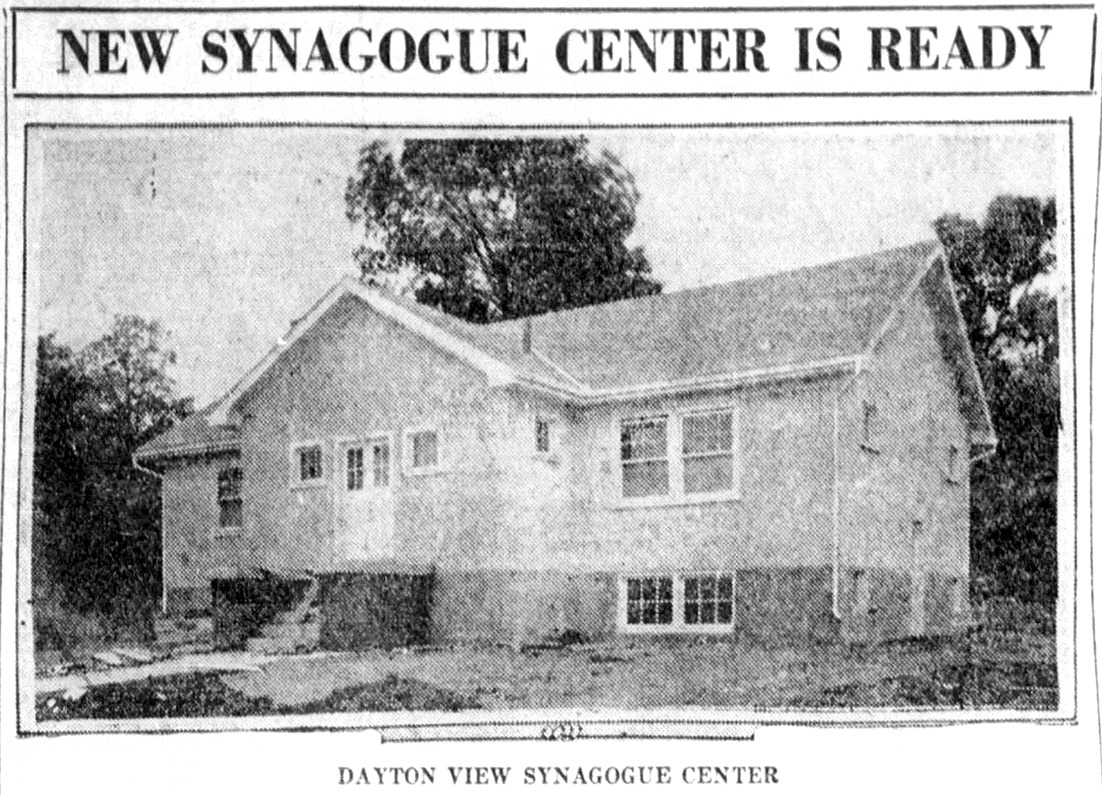

In Dayton, two Jewish congregations opened synagogue center facilities: the two-year-old Dayton View Synagogue Center in 1924 (Dayton’s first Conservative congregation), and Temple Israel in 1927 with the opening of its Community House on Salem Avenue.

In her 1928 report to the community, Fisher lamented the challenges the JCC faced from this competition — and from the JCC’s own inertia.

“Our efforts in the field of recreation can best be described at present as being in a transitional stage,” she wrote. “The situation is somewhat complicated — with the recent erection of the Temple Center for congregational facilities and a limited program for recreational activities are almost wholly on a congregational basis.

“Attempts are being made by other groups, such as the Dayton View Center, The Dayton Hebrew Institute, the B’nai B’rith and here and there spasmodically we hear a new organization come into being, with no definite program — no definite leadership.”

She described the JCC’s recreational activities as limited in number to very young children because of inadequate physical equipment, lack of proper facilities, and limited funds.

“With no adequate Young Men’s and Young Women’s Hebrew Association in Dayton, there is very little doubt that between the Temple and the Jewish Community Center on the other hand…a large proportion of Dayton’s Jewry is unserved insofar as organized recreation is concerned.”

As the JCC was passing out of its “settlement” stage because Jewish immigration to the United States had been virtually shut down, Fisher urged the JCC to expand its recreational facilities and activities.

But with the Great Depression, America’s entry into World War II, and numerous emergency campaigns to support the new Jewish state, Fisher’s vision wouldn’t come to pass in Dayton until the 1960s.

By the mid 1930s, most of Dayton’s Jews had moved on from the East End; they lived in Lower Dayton View. The Federation sold the Green Street JCC building in 1941.

Fisher departed Dayton in 1943 to become director of the Jewish Children’s Home in Brighton, Mass.

Through the end of World War II, the Dayton Jewish community’s highest priority was once again supporting the war effort in every way possible: through donations to the Dayton War Chest, supporting Dayton’s Jewish Army Navy Committee, and U.S.O.-Jewish Welfare Board.

Synagogues and Hadassah hosted local dances, entertainment, and holiday meals for hundreds of Jews in the military with War Chest funds. Dayton’s B’nai B’rith shipped care packages to local Jewish soldiers stationed overseas. Young Jewish Women established the War Activities Group under the Federation’s auspices.

It was a time when young Jewish adults arrived in Dayton in significant numbers because of the war. Plenty of them found spouses here and would stay. Others would stay because their work here continued after the war.

This would contribute to Jewish Dayton’s peak population of about 7,200 in the early 1970s and the push for an expansive JCC facility equal to those in any large American city.

By 1950, Fisher had returned to Dayton and opened her own employment agency. Two years later, when she died at age 67, she willed the remainder of her estate to the Montefiore Jewish Home for the Aged in Cleveland.

Related: Dayton’s JCC at 100 – Part Two – A place to call home

Related: Remember the time capsule? We opened it for the JCC’s centennial.

To read the complete June 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.