Libby Copeland: DNA testing reveals family secrets, complicates identity

By Sophie Panzer , Jewish Exponent

In 2012, a woman named Alice took a DNA test and expected it to reveal that her entire family hailed from Irish American and British ancestry.

Instead, the test revealed that half her DNA was Ashkenazi Jewish.

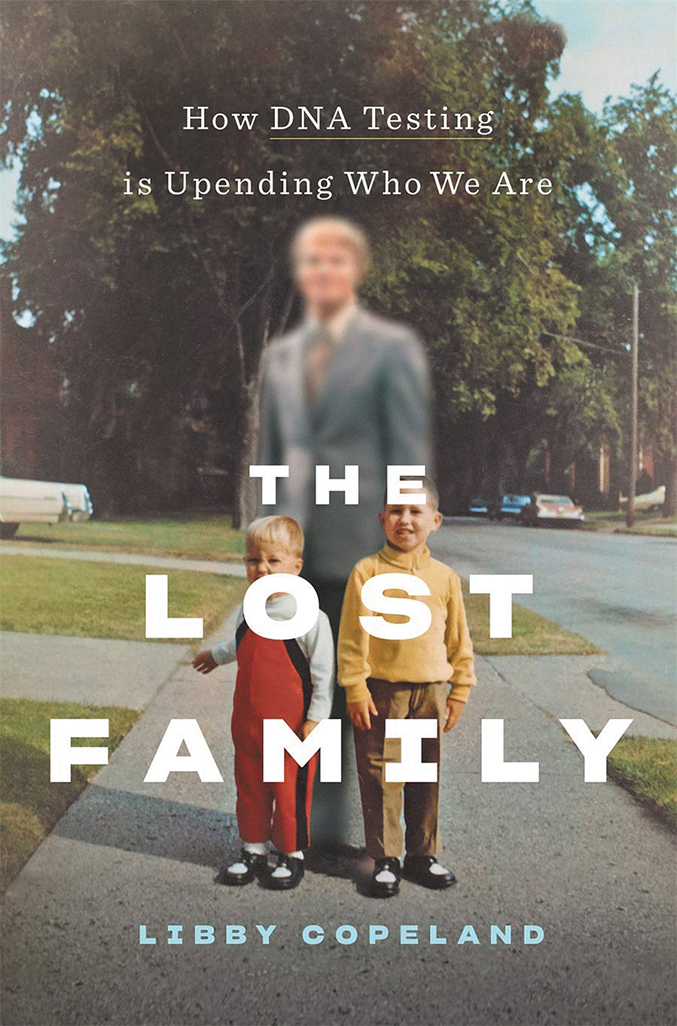

Her attempts to understand the results and her family’s history are the central story of journalist Libby Copeland’s book The Lost Family: How DNA Testing Is Upending Who We Are.

Copeland’s writing explores the science of DNA tests as well as identity, family secrets, and the cultural implications of unprecedented access to genetic information.

In Dayton, the JCC Virtual Cultural Arts & Book Series will host a Zoom discussion with Copeland at 7 p.m., Wednesday, Dec. 2, in partnership with Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, presented in memory of Marcia Jaffe.

Copeland will share her experiences touring the facilities of testing companies like Ancestry and interviewing individuals whose lives have been impacted by test results.

Copeland focused on Alice’s story because she dedicated 2½ years to understanding the mystery of her background. None of the scenarios that typically lead to unexpected genetic testing results, such as adoption or unknown paternity, explained her Jewish ancestry.

“She builds essentially a database of her own DNA, and she basically makes this into her full-time job and with the help of her sister,” she said.

Another story in The Lost Family features a woman who finds out she has 22 donor siblings and reaches out to her donor father. After he finds out about his donor children, the man grapples with how he should form relationships with them.

“That is a question that is profoundly interesting in terms of privacy, and also more broadly in terms of how we find family, and how we think about the elasticity and the capacities of the human heart,” Copeland said.

As DNA testing companies expand their databases of genetic information, they threaten the privacy of sperm donors who were initially promised anonymity when they donated in the ’60s, ’70s and ’80s.

Even if the donors themselves do not choose to test, their descendants can use the sheer number of people in DNA databases to trace them.

“If you are genetically related to someone and they’re not in the databases, you may be able to use a second, third, first cousin that you find in order to figure out that person’s identity if you’re willing to do a little bit of genealogical research,” Copeland said.

Insurance discrimination is another concern. Copeland said that although some federal protections exist against genetic discrimination, it is still possible for insurance companies to deny people coverage based on their genetic history if they are able to access test results.

DNA testing also raises questions about the meaning of ethnicity. Copeland spoke with a scientist at the genetic testing company 23andMe who was concerned her work was being used to reinforce incorrect ideas about racial difference, particularly White supremacy.

People who see their DNA represented in a pie chart without understanding how genetics work may believe that the diagram represents rigid, ingrained differences between ethnic populations.

However, just because a test can show that 20 percent of a person’s DNA traces back to South Korea and another 80 percent traces back to Sweden, this does not indicate there are significant differences between South Koreans and Swedes; it means they hail from different parts of the world and share certain genetic markers with populations in the region.

Although misinterpretation is always a risk, Copeland found that the sources she interviewed had more nuanced perspectives of their ethnic heritage and family after getting their results. Alice was no exception.

“She didn’t say, you know, ‘My Irish experience doesn’t count because now I’m only half-Irish, genetically speaking,’ and nor did she say, ‘My Jewishness is meaningless and something to be dismissed,’” Copeland said. “She said, ‘Yes, and.’ Which I think is incredibly beautiful.”

The JCC Cultural Arts & Book Series in partnership with Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History presents Libby Copeland via Zoom, 7 p.m., Wednesday, Dec. 2. Free. Register here.

To read the complete December 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.