Let there be light

Considering Creation: A Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

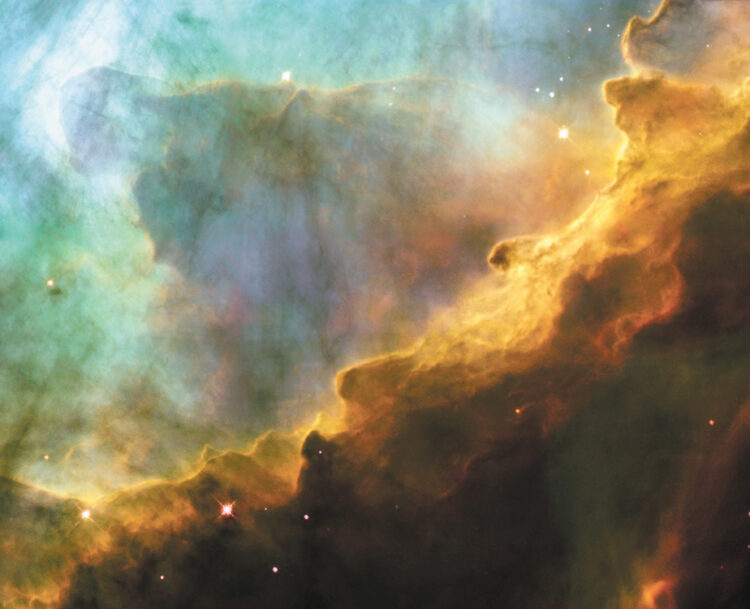

Creation began with an infinite divine light, the Ohr Ein Sof, according to the Torah’s mystical interpretation found in the Kabalah. To create an empty space where physical and spiritual worlds could be created, God contracted the divine light (tzimtzum) and created vessels to hold its concentrated energy. Not strong enough, the vessels shattered (shevirat ha-kaylim), sending sparks of celestial light throughout the universe.

While this Kabalistic interpretation of Creation may seem fanciful and farfetched, it accords surprisingly well with the biblical text.

“God said, ‘Let there be light’; and there was light. God saw how good the light was, and God separated the light from the darkness. God called the light Day, and the darkness He called Night. And there was evening and there was morning, a first day (Gen. 1:3-5).”

Although stylistically very different, both the Bible and Kabalah are of like mind about the distinctive identities of dark and light, the transcendent nature of light, and light’s quality of goodness.

It is noteworthy that these ancient texts foretell modern science’s account of the evolution of the universe.

According to the Big Bang Theory, an initial exploding expansion of radiation from a single timeless and spaceless primeval atom of extremely high density and temperature suffused space with a bright light that would not have been visible to the human eye.

As the universe cooled, the radiation differentiated into various wavelengths including visible light.

Primordial elements coalesced, creating stars and galaxies. Surrounding them arose a form of unseen dark matter that doesn’t emit, absorb, or reflect light but has mass and gravitational pull, echoing the biblical notion of darkness. Remarkable, no?

And yet, science only tells us what exists. Torah is a guide to why we exist and how to live. So how can “Let there be light” and “God saw it was good” help us understand the purpose of being and the way to live?

“Light” expresses much more than an electromagnetic wavelength. We can shed light on something or bring something to light; enlighten someone or see the light ourselves; or see someone or something in a new light.

If something sees the light of day, it comes into existence or is made known to the public. Light signifies perception, recognition, insight, and creativity.

We can be a ray of light, bringing hope to a difficult situation, or do things with a light heart, radiating cheerfulness and optimism in the world. In the Kabalistic view, our job is to gather the sparks of God’s scattered light — tikun — and use them to help repair the world. As the Jewish expression goes, “A little bit of light pushes away a lot of darkness.”

In Proverbs 6:23 we read, “For the commandment is a lamp, and the teaching is light.” A popular folk song captures the same sentiment with words from the Zohar, “Torah orah, Hallelujah — the Torah is light, Hallelujah!” Torah study brings enlightenment.

The lights of candles and lamps express the sanctity of time (on Shabbat and festivals), the sanctity of place (in the Holy Temple and synagogue), and the sanctity of remembrance (for yahrzeit and Yad Vashem).

Commenting on the Temple menorah, the late Rabbi Adin Steinsaltz noted that it served no practical purpose: its light serving only as a symbol of the holiness of that place.

Yet, when the Temple was destroyed, the menorah came to be the premier symbol of Jewish existence. Light conveys the sanctity of time, place, memory, and continuity.

Straightforward and uncomplicated, “God saw it was good” expresses the inherent optimism in Creation, that good will ultimately prevail, suggests author and commentator Dennis Prager.

Biblical commentator Leon Kass explains it is an affirmation that what has been created — divine light — is complete and fitting for its purpose in relation to the unfolding whole.

Looking through the lens of social anthropology, Rabbi Nachum Sarna notes, “It banishes the ancient pagan notion of inherent, primordial evil,” a cosmos built on a mythological brew of fates and evil forces. In the biblical view, Creation is infused with divine goodness, and evil’s place is only as a moral quality.

The Lubavitcher Rebbe proposed that God means both light and darkness have the potential for goodness. “All the world — even the darkness — should become a source of light and wisdom.”

The Midrash asks, “From where was the light created?” The answer is whispered: “The light was created from the place of the Holy Temple. The Holy One enveloped Himself in it like a cloak, and the light of its splendor shone from one end of the world to the other.”

The light that permeates all Creation is divine, and it is visible to those who look for it. But it is inert unless we put it to use. Our job is to bring more light into the world.

Ignite the light.

Shine a light to improve perception, recognition, insight, and creativity.

Bring the lights of hope, cheerfulness, and optimism to the world.

Gather sparks of light and help repair the world.

Immerse in the light of Torah.

Kindle lights to sanctify time, place, memory, and continuity.

Create light in the darkness.

How will you ignite the divine light today?

Literature to share

I Wanted Fries with That: How to ask for what you want and get what you need by Amy Fish. This is more than just a practical handbook — it’s a delightful read. An experienced professional problem solver, Fish divides this slim volume into three parts: I want my problem solved, I want you to change, and I want justice to be served. In each section, she provides clear methods for addressing a variety of troublesome scenarios, illustrated with realistic and humorous examples. I read this in one sitting and plan to read it again.

American Golem: The New World Adventures of an Old World Mud Monster by Marc Lumer. The legendary tale of the Golem of Prague takes a new twist in this American immigrant story with real kid-appeal. Newly arrived from the Old World, a young boy builds a golem for protection against bullies and other dangers. But he soon discovers America is a very different place, and the golem needs a new job. Historical photographs of New York City and graphic novel-style illustrations are a perfect complement to the narrative in this delightful tale for elementary readers and families.

To read the complete November 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.