A heritage of common sense

Our Dual Heritage Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

As a kid, my peers and I could read a tape measure. It was just common sense. Yet a recent radio report confirmed by an online contractors’ blog, noted that construction managers are regularly faced with potential hires that have no idea how to read a tape measure.

That’s not just a professional shortcoming. According to a recent survey, nearly two out of five American adults (and half of the college-age crowd) can’t make any common repairs without using the internet. Unclogging a drain, installing a drywall anchor, replacing a leaky faucet washer, even patching drywall necessitates turning to Google for help.

The lack of common sense — practical skills, basic knowledge of how the world works, seeing the obvious, thinking clearly, and doing the right thing — seems to be pervasive.

Hairdryers warn “Do not use in bathtub” and “Do not use while sleeping.” A microwave oven manual is labeled “Do not use for drying pets.” Styrofoam packaging warns “Do not eat.” An iron is labeled, “Do not iron clothes on body.”

Spectacular examples of a lack of common sense are recorded in the annals of the Darwin Awards, which “commemorate those who improve the gene pool by removing themselves from it in a spectacular manner.” Consider the young man who piloted a golf cart towed by a garden hose behind a vehicle on a California state highway. Or the two Louisiana drivers who decided to “shoot the gap” of an open drawbridge. Or the lawyer who decided to demonstrate the boardroom’s “unbreakable windows” by throwing himself against them.

It’s common sense to pay your bills on time, not spend what you don’t have, and start saving when you begin working. To work hard and keep your promises. To first do what you have to do, and only then do what you want to do. And to follow the old-fashioned common sense of “graduate, find a job, get married, and have kids in that order,” newly coined as the “success sequence” because of its proven modern-day relevance across widely divergent socioeconomic groups.

And yet, to echo the words of Mark Twain, “I’ve found that common sense ain’t so common.”

It’s therefore surprising that “Common sense…is one of the most revered qualities in America,” according to writer and professor Dr. Jim Taylor. “It evokes images of early and simpler times in which industrious men and women built our country into what it is today.”

Certainly, in the 16th and 17th centuries, America’s settlers and adventurers relied on common sense — at that time understood as “the plain wisdom that everyone possesses,” to survive and flourish.

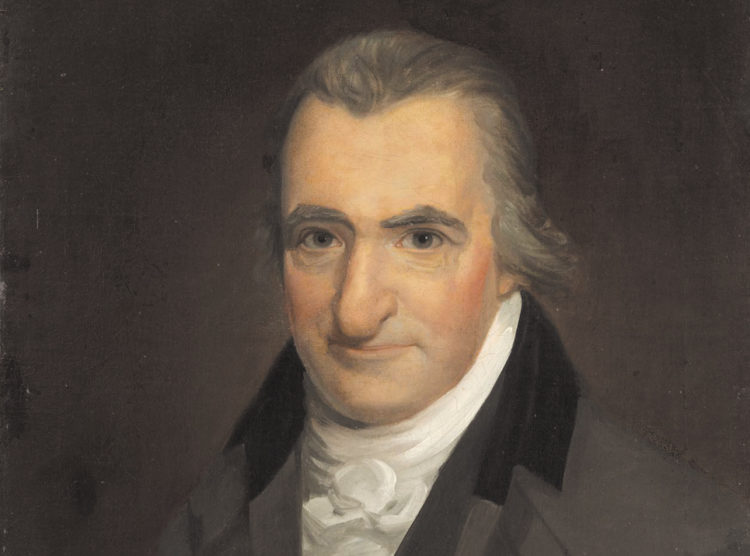

When Thomas Paine wrote the revolutionary pamphlet Common Sense in the 1770s, linguistics scholar Gary Martin notes, “the term was widely used to mean ‘primary truth,’ that is, the unquestionable beliefs (or self-evident truths) gleaned through life experience.”

A colonial bestseller and “the match that lighted the fuse of independence,” Common Sense was deliberately written in the vernacular, in a common sense, democratic style, writes former LA Times columnist and book critic David Ulin. He goes on to note “this cut both ways, galvanizing the public even as it frightened many of the gentry.”

Inspired by Paine’s insights, the authors of the Declaration of Independence began their case for separation from England with, “We hold these truths to be self-evident…”

Their meaning was, “‘we believe this declaration to be common sense,’” Martin writes, highlighting the connection to Paine’s literary blockbuster.

And the Declaration’s common-sense truths had their roots in the Hebrew Bible. Equality. Life. Liberty. Pursuit of Happiness.

It’s impossible to miss the Declaration’s biblical connections. In Genesis 1, all humans are created equal in the Divine image. The Declaration goes on to say all humans are endowed “by their Creator with certain unalienable Rights,”divinely given rights that cannot be taken away or denied by worldly rulers. They are repeatedly identified throughout the Bible. In Genesis 1 and again in Psalm 139:17, that life is divinely given. In Exodus 12:18, that liberty is divinely won. In Deuteronomy 28:19, that happiness is divinely commanded.

Beyond the self-evident common-sense truths rooted in the Bible, argued in Paine’s Common Sense, and proclaimed in the Declaration, Judaism also embraces an everyday application of common sense.

Appearing in various forms in the Bible more than a hundred times, it’s known in both Hebrew and Yiddish as seichel, meaning good sense, reason, intelligence, smarts, cleverness, or even wisdom, according to Moment Magazine senior editor George Johnson. Rabbi Julian Sinclair adds, “Seichel is derived from the word meaning to be bright or see clearly.”

Thus, when we use our seichel, our common sense, we bring a bit of the Divine light into our everyday world.

One of the greatest Jewish leaders in America, the late Rabbi Menachem Mendel Schneerson, understood common sense stands side by side with the spiritual. As the story is told, the Rebbe received a letter from a Chasid concerned about a series of thefts from his Crown Heights home.

“Perhaps I should have my mezuzos checked?” the man suggested. The Rebbe replied, “Perhaps you should check the security of your windows.”

If common sense really is one of the most revered qualities in America, part of our essence as Jews and as Americans, perhaps we ought to start using it a bit more often.

Literature to share

The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure by Greg Lukianoff and Jonathan Haidt. “What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker. Always trust your feelings. Life is a battle between good people and evil people.” These provocative statements form the thesis of Coddling, an expansion of a 2015 Atlantic cover story about the widespread influence of “safetyism.” Lukianoff and Haidt explore its connection to skyrocketing problems in higher education, mental health, moral and intellectual development, and life success among today’s youths. Informed by their backgrounds in law, education, business, and psychology, the authors’ analysis offers common-sense advice that crosses political and cultural divides.

Picture Girl by Marlene Targ Brill. The tale of young Luba and her Jewish family, who escape the Cossacks and travel across stormy seas to Ellis Island. There the family’s twins become ill, and they face deportation when the Ukrainian immigration quota is filled while the family’s twins recover. But Luba’s spunky demeanor and artistic hobby save the day. Loosely based on the life of artist Louise (Luba) Dunn, this chapter book for elementary readers is an engaging read and an excellent introduction to Jewish history between the world wars. Great for home and classroom settings.

To read the complete February 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.