Jews & Dayton’s booze trade

On the centennial of Prohibition in Ohio, a look back at the celebrated leaders of Dayton’s liquor industry — and how Dayton’s Jews navigated Prohibition

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

It’s not commonly remembered today that for centuries, Jews were involved in all aspects of the liquor business in Poland: production, exporting, wholesale and retail distribution, and even running saloons. Polish nobility did their best to keep Jews from achieving success individually and collectively — unless the Jews could provide them with help they could obtain from no other source.

A census of Jews in 1764-65 recorded that approximately 80 percent of Jews living in Polish villages and about 14 percent of Jews living in Polish towns and cities were involved in the production and sale of beer and vodka, according to the YIVO Institute For Jewish Research. The Jews were known for their moderation when it came to drinking, and also were able to import Polish grain crops to markets through their connections with Jews in other countries.

Jews were also active in Hungary’s wine business beginning in the 1700s and in France following Napoleon’s opening of the ghettos of Central Europe.

It’s no surprise that when Jews began arriving in America, some joined the liquor trade. And they thrived. The Freiberg family of Cincinnati and the Bernheim family of Louisville became significant donors to general and Jewish causes.

So too in Dayton, Jews and the liquor trade — and philanthropy — have shared a notable history.

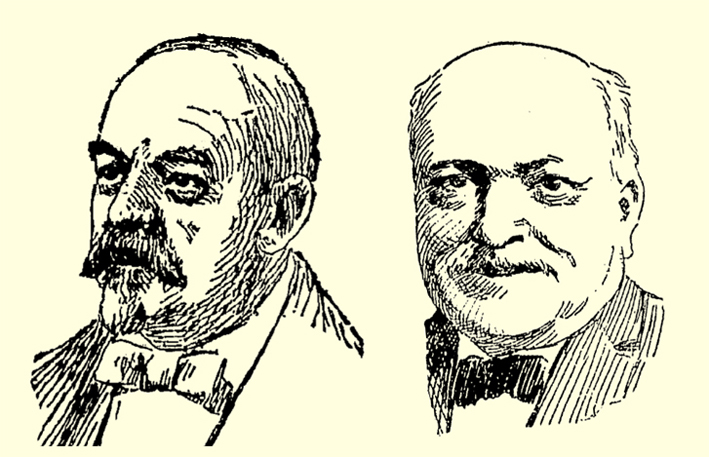

Our story begins in 1859, with Isaac Pollack and Solomon Rauh.

Both in their 20s, Pollack and Rauh had arrived here as part of the wave of Jewish immigrants from Central Europe: Pollack from Riedseltz, France, and Rauh from Essingen, Bavaria.

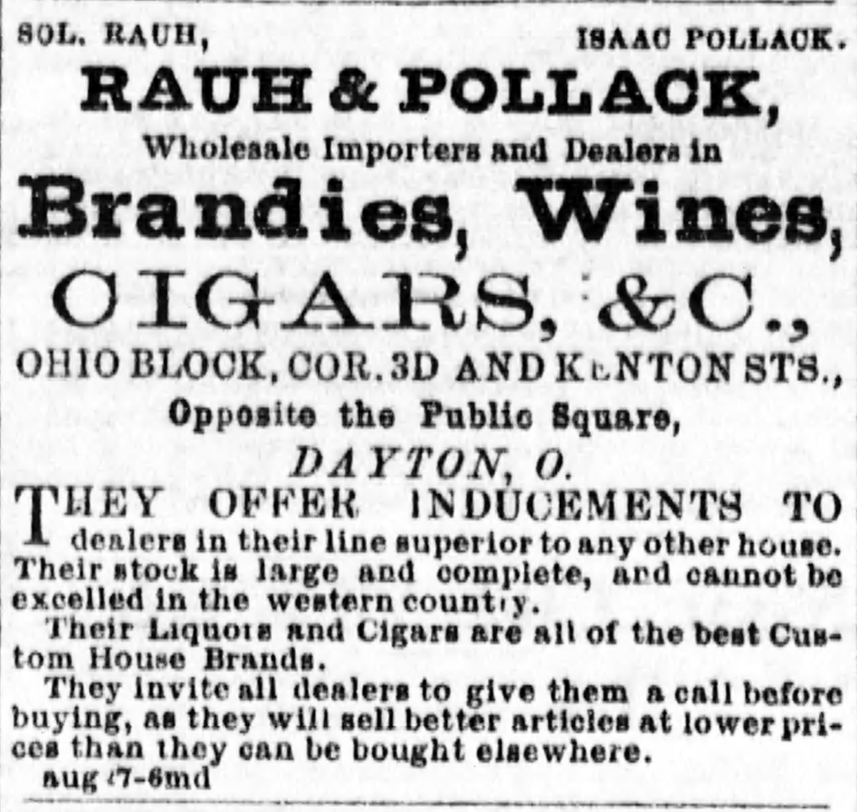

Rauh and Pollack began selling wholesale wines, liquors, brandies, and cigars at Third and Kenton Streets. They advertised their business in the Daily Empire beginning in September 1859. This was Dayton’s first wholesale liquor store.

By September 1862, Pollack was considered a Civil War hero. He had been appointed a corporal among the Squirrel Hunters, the civilians who assisted the federal government in defending Cincinnati from a Confederate attack.

The partners prospered rapidly. In 1876, they built identical mansions for their families on adjacent lots: 319 and 321 W. Third St. in Dayton. According to lore, in the shade of a nearby tree, Pollack and Rauh flipped a coin to determine who would occupy which house; the Rauhs took 321, the Pollacks 319.

The Pollack House still stands today, though in a different location; in 1979 it was moved to 208 W. Monument Ave. and now houses the Dayton International Peace Museum.

Rauh and Pollack were among the Jews who lived downtown and worshiped at the predominantly German Jewish B’nai Yeshurun, now Temple Israel. They were founding members of the Standard Club, the social and literary club that was effectively an extension of B’nai Yeshurun.

Rauh married Jeanette Lebensburger, whose father, Joseph, was the first leader of Dayton’s early Jewish community. It was Joseph Lebensburger who in 1850 established what would become B’nai Yeshurun.

A staunch supporter of the Democratic party, Pollack was a major donor and champion of St. Elizabeth’s Hospital when it was established. He was also a member of St. John’s Lodge of Masons and Dayton’s B’nai B’rith lodge.

“His cheerful and amiable disposition won him many friends,” the Dayton Daily News wrote of him.

Rauh was also a director of the Merchants’ National Bank and a longtime president of both B’nai Yeshurun and B’nai B’rith. The Dayton Daily News described him as “genial, whole-souled and charitable…one of the leaders of this community, and one of the acting spirits in movements that meant the advancement of Dayton.”

After 30 years in business together, Pollack decided to split from Rauh around 1893. This was the year when Sol Rauh & Sons, then at 107 E. Third St., began to list itself as also in the distilling business.

his own brand

of whiskey

It’s possible that Rauh’s desire to add distilling to the business led to the separation with Pollack, who would retire from his business in 1906 and died two years later at 71.

Rauh & Sons kept distilling its own whiskey until at least 1913. The Rauh business was completely destroyed in the fire immediately after the Great Flood of 1913. Two months later, it advertised in the Dayton Daily News that it had relocated and was “now prepared to fill all orders promptly.” It continued to list itself as “distillers and wholesale liquor dealers.”

Rauh & Sons would rebuild and return to its location at 107 E. Third St.

After Sol Rauh’s death in 1915 at 79, his son Ed took over the business. Sol Rauh brought Ed into the business after he bought out Isaac Pollack in about 1893.

Ed Rauh was a sportsman, well known as an enthusiastic harness horseman. He owned several trotting horses.

In 1919, Ed Rauh’s business in Williams’ Dayton City Directory was listed at 107 E. Third St. as “wholesale non-intoxicating beverages.”

An enthusiastically “dry” state, Ohio entered Prohibition May 27, 1919, nearly eight months before the 18th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution — known as the Volstead Act — went into effect Jan. 17, 1920.

The Volstead Act prohibited the “manufacture, sales or transportation of intoxicating liquors for beverage purposes” in the United States.

Whether or not Ed Rauh went into the soft drink business as a front and remained in the whiskey business as a bootlegger is unclear. Descendants of Rauh who were contacted for this story didn’t know the answer.

In any case, Rauh’s business in the 1921 city directory was listed at the same location, but now as Rauh’s Tire & Auto Supply.

Prohibition’s sacramental wine loopholes —and scandals

To avoid violating the freedom of religion clause of the U.S. Constitution’s First Amendment, the federal government did allow exemptions to Prohibition, since Catholics, some Protestants, and Jews use wine for religious purposes.

Wine could still be produced and sold for use in religious services, and households were allowed to make up to 200 gallons of wine per year for “non-intoxicating” family consumption.

It was fairly common in those days for Jews to make their own wine at home, and an accepted practice among Jews was to make wine from raisins when fresh grapes were unavailable.

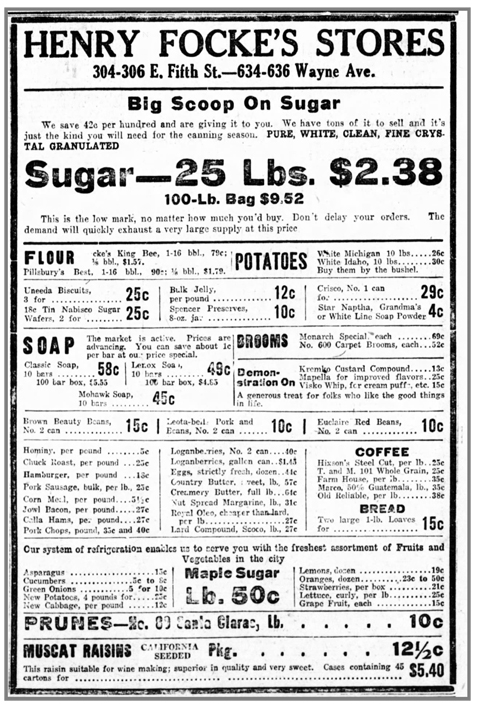

A few weeks before Prohibition began in Ohio, Henry Focke’s Stores, located in Dayton’s Eastern European Jewish neighborhood along Wayne Avenue, advertised in the Dayton Daily News a sale on Muscat raisins in bulk, “suitable for wine making.”

In February 1920, the federal government set the limit on the sale of kosher wine at a maximum of 10 gallons to each individual of the Jewish faith per year for religious use.

The way Jews were to legally obtain sacramental kosher wine for home use under the National Prohibition Act opened up a new set of problems.

Congregational rabbis were to determine the quantity to be used by each individual member up to the legal maximum. The sale and delivery of wine was either to be made to the rabbi, or the rabbi would provide congregants with the proper paperwork to make a “withdrawal” from an authorized sacramental wine dealer.

The congregation was responsible for paying the dealer for the wine based on the rabbi’s determination of the needs of his congregants.

However, rather than pay the rabbi or the congregation directly for the wine, congregants were directed by the act to make a contribution to the synagogue “for general purposes and not as a payment for a certain quantity of wine.”

Add to this that according to Jewish law, Kosher wine must only be handled by Sabbath-observant Jews — from crushing the grapes through bottling (unless the wine is boiled) — these policies, which the Bureau of Internal Revenue put in place to safeguard against bootlegging in the Jewish community, would have the opposite effect.

Unlike sacramental wine in Christian traditions, which is used in church, wine in Jewish rituals is predominantly used in the home: to sanctify the beginning and mark the ending of Shabbat each week, and for seasonal Jewish festivals and holidays.

Leaders of the Reform and Conservative movements saw the potential for abuse. In short order, they urged their members not to use wine for rituals even though it was legal. They encouraged their congregants to use grape juice instead.

The consensus of U.S. Orthodox rabbis at the time was that although grape juice was acceptable, kosher wine was preferable for religious use.

Orthodox rabbis, who did not fall neatly into national umbrella organizations as did Reform and Conservative rabbis, saw no reason to refrain from the use of kosher wine, particularly since the U.S. government allowed its use for sacramental purposes.

If Jewish Daytonians didn’t produce their own wine, congregants of Beth Abraham and Beth Jacob synagogues could procure it through their rabbis via authorized kosher wine dealers in Cincinnati.

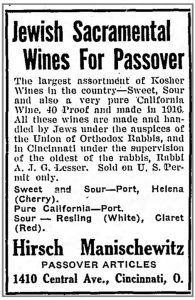

Hirsch Manischewitz, a member of the family that owned the maztah-baking business in Cincinnati, was listed in The American Israelite as selling kosher wines for Passover in April 1921 at 1410 Central Ave. in Cincinnati (Manischewitz wine didn’t appear until 1947).

And Rabbi Rudolph A. Funk of Hamedrash HaGadol Synagogue in Cincinnati legally distributed sacramental wine from his store at 1514 Central Ave. in Cincinnati from 1923 to 1925.

According to Marni Davis in her seminal 2012 book, Jews and Booze: Becoming American In The Age Of Prohibition, “‘Rabbis’ (some of whom were not in fact Jewish) claimed new and enormous congregations filled with members named Houlihan and Maguire.”

She adds that “Rabbis requested wine on behalf of fictitious or long-dead congregants, or sold their legitimately acquired wine permits to bootleggers. The sacramental dispensation also made available a far wider variety of alcoholic beverages than is traditionally present in Jewish practice.”

Leaders of the Reform and Conservative movements, more acculturated to American life, recognized that these scandals in the name of religion fanned the flames of hate against the Jews. Their concerns were justified.

Antisemites such as Henry Ford and the newly revived KKK used these scandals of the early 1920s to further pillory the Jews as a threat to American morality.

Davis emphasizes that Americans of all backgrounds were involved in illicit liquor commerce during Prohibition.

But the “prevalence of Jewish and Italian involvement” and the attention it received in the press didn’t help when the U.S. Congress overwhelming passed the Emergency Quota Act of 1921 and the Immigration Quota Act of 1924, which slashed the annual number of émigrés from Southern and Eastern Europe allowed into the United States by 87 percent.

Orthodox rabbis in America at the time — who had been reared in viciously antisemitic Eastern Europe — tended to believe that those who hated Jews would continue to hate Jews no matter what Jews did or didn’t do.

In her 1991 scholarly article for the American Jewish Archives Journal entitled Orthodox Rabbis React To Prohibition, Hannah Sprecher notes that “while rabbis in Europe had essentially ruled over their communities, in America, a rabbi ‘at best found employment with a congregation that gave him little security and meager wages.’”

Sprecher sums up that unlike rabbis in the more affluent Reform movement, “Orthodox rabbis in America were suffering under crushing poverty, and the wine trade was vital to their survival.”

One rabbi who publicly railed against Jews’ use of sacramental wine was Rabbi Samuel S. Mayerberg of Dayton’s Reform congregation, B’nai Yeshurun. This was also the congregation of the Rauh family.

As the editorial contributor to The Ohio Jewish Chronicle, based in Columbus, Mayerberg wrote in the March 2, 1922 issue, “In many large cities pseudo-rabbis have been caught with large amounts of wine in their possession. They have been found to be ordinary boot-leggers. When such cases are brought to the attention of the public they immediately bring the Jewish name into disrepute.

“While it seems now that it will be impossible to have this harmful law repealed, at least for some time, it is to be hoped that all Jews, be they Reformed, Orthodox, or Conservative Jews, will refrain from the purchase of wines for even religious purposes. Nothing can work greater harm upon the Jewish name than the feeling, which is prevalent, that all Jewish rabbis are boot-leggers and that every Jew does his best to circumvent the national prohibition law.”

Mayerberg wrote to a colleague in 1926 that he believed in temperance, not Prohibition. “I personally believe that the enactment of the Prohibition laws has brought more harm than good,” he wrote. “I know that we have more drunkenness in Dayton today than we ever had before Prohibition and I know that our Workhouse is filled with violators of the Prohibition laws. It has not reduced crime and has not ameliorated conditions of poverty.”

The lowest point in the sacramental wine scandals of the 1920s hit in 1926, when a federal grand jury investigated 600 rabbis in New York City for greatly exaggerating the number of people in their congregations.

In 1925, when sacramental wine withdrawals were at their peak, the federal government reduced the amount of sacramental wine available to families by half. It also took away the 200-gallon home winemaking permit, revoked all existing rabbinic wine permits, required that all rabbis reapply, and continued to tighten restrictions and bookkeeping safeguards.

Rauh switches to near beer

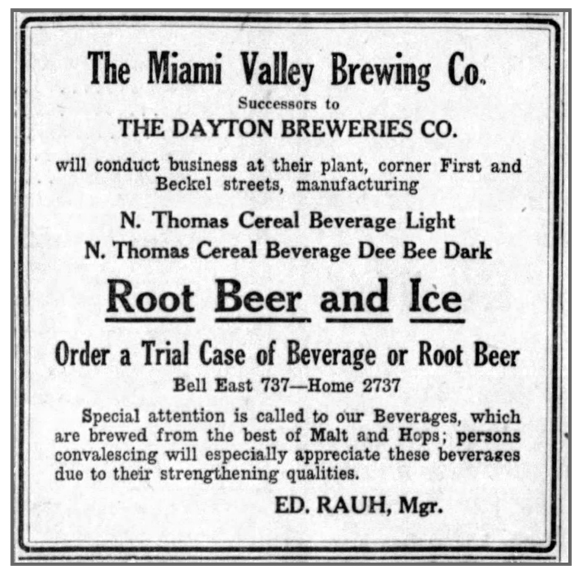

How did Ed Rauh fare as the decade progressed? In 1924, he was listed in the Williams’ Dayton City Directory as manager of the Miami Valley Brewing Company.

As rare as it was, he oversaw the legal brewing of near beer at Dayton’s only remaining brewery plant.

In August 1923, the Dayton Daily News announced the project.

“Many new formulas have been obtained through which Rauh and his associates hope to make the new near beer so palatable that Daytonians will show a decided preference for it, Rauh says.”

Whether or not his venture was also a front for full-strength beer is lost to history.

According to Curt Dalton in Breweries of Dayton: A toast to brewers from the Gem City: 1810-1961, the Miami Valley Brewing Company was the successor to numerous breweries that operated at First and Beckel Streets in Dayton beginning in 1865. Among the owners were George Weedle and Nick Thomas.

In 1906, several Dayton breweries including Nick Thomas merged into the Dayton Breweries Company to fight the growing strength of the Prohibition movement, which was already strong in Ohio.

But when Prohibition was on the immediate horizon, the combined company continued to lose business. One by one, the seven breweries that made up Dayton Breweries Company closed as the state went dry, until the First and Beckel site was the only one left.

In April 1933, with the death of Prohibition in sight by the end of the year, the Miami Valley Brewing Company announced it had been sold to a syndicate of businessmen including Rauh in Dayton and brothers I. George Kohn and Morton Kohn of Cleveland. With Rauh as manager, they invested $100,000 in the plant to expand and modernize bottled beer production. The brewery was also the first in Dayton to produce beer in cans.

But by November, Rauh severed his connection with the brewing firm; he died five years later at 73.

In 1934, the Kohns brought part owner Leonard S. Becker from Cleveland to serve as treasurer and sales manager of the Miami Valley Brewing Company. In short order, Becker also became an active member of Dayton’s Jewish community.

Becker was elected president of the Zionist Organization of America Dayton District in 1942 and became president of the Jewish Community Council of Dayton (now the Jewish Federation) in 1949, a crucial time of emergency campaigns to bring DPs out of Europe and to help the fledgling state of Israel. He left the brewing company around 1949 to oversee Ralph Kopelove’s scrap metal business in Dayton. Becker died at 82 in 1989.

With I. George Kohn’s departure from the Miami Valley Brewing Company in 1946 and Morton Kohn’s death in 1950, the plant closed that year.

Marshall Weiss, editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer, is the author of Jewish Community of Dayton and project director of Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, a new initiative of the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton.

To read the complete May 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.