Animals tell tales

The Power of Stories Series

Jewish Family Education with Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Every day, the renowned medieval scholar Maimonides visited Egypt’s sultan, whom he served as a court physician. During the long donkey ride, Maimonides voiced his thoughts aloud and the donkey would listen and reflect.

“You must accept the truth from whatever source it comes,” the rabbi might say. Or, “The purpose of the Law is to develop self-discipline so we might keep distant from either extreme.” Or, “Silence is a fence around wisdom.”

Upon his return, in between his rabbinic duties, he would treat his own patients and write late into the night.

Exhausted, Maimonides wondered if riding a horse would save time. Sure enough, with a speedy horse, the rabbi’s travels were shorter, and he had more hours for his work at home.

But his donkey missed hearing the rabbi’s wisdom, and the rabbi soon discovered he no longer had time for just thinking.

Originating in oral tradition, Jewish stories and texts involving animals have spanned its nearly 4,000-year history. Biblical and Yiddish narratives. Parables, proverbs, and riddles. Chasidic tales and fox fables. Even legal texts and prayers.

Animals are liberally peppered throughout Jewish literary works.

Why animals? The answer may originate in Genesis 1, when God creates nefesh chaya, living animals. God then says, “Let us make man in our image, according to our likeness.”

In our image may refer to the animals.” writes Dennis Prager, author of The Rational Bible. “This man is physiologically both animal-like and man-like.”

In Genesis 2, God permanently distinguishes humans from animals by breathing into the man nishmat chayim, a transcendent living soul.

However, humans still retain their kinship and singular fascination with animals, the only other animate elements of Creation.

We can see ourselves in the personalities and actions of animals. That makes them ideal characters for myriad literary genres.

We can see ourselves in the personalities and actions of animals. That makes them ideal characters for myriad literary genres.

“Animals can bring silliness and incongruity to a story,” notes children’s author Mary Gibbs, “making it more enjoyable,” and communicating important life lessons and big ideas in memorable ways. “But,” she continues, “they also add a degree of emotional distance for the reader, which is important when the story message is personal, painful or powerful.”

Animal characters can even provide a voice to those who are not free to speak.

Because they have universal appeal — across ages, cultures, social rankings, time, and place — animal tales allow everyone to join in the conversation.

Peaceful pursuit. When Emperor Hadrian decreed the rebuilding of Jerusalem’s Temple, enterprising merchants set up along travel routes and supplied returning Diaspora Jews with all their needs. Fearing the returnees would reclaim their ancestral lands, locals claimed the mushrooming Jewish population would openly revolt.

They advised the emperor to order the Jews to change either the Temple location or its dimensions, “and they will recant on their own!”

But the Jewish population grew mutinous, so the sages turned to Rabbi Yehoshua ben Chananya, who spoke to the people.

“A lion was devouring prey and a bone got stuck in its throat. It said, ‘I will give a reward to anyone who removes it.’ An Egyptian heron put its long beak into the mouth of the lion and extracted the bone.

“It then said to the lion, ‘Give me my reward.’ The lion responded, ‘Tell others, “I went into the mouth of the lion in peace and I came out in peace”‘ — and there is no greater reward than that.”

Said Chananya, “It is enough for us that we entered this nation in peace and came out in peace.”

Tabletop lesson. Plodding wearily, a skinny lion met a fat dog who mocked him.

“Where are you going? Why are you so thin? It would be easy for you to be among men, to guard and carry and serve. Then you could eat to your heart’s content, even as I, their servant, am fat and no wanderer. Even when they bind me with ropes, meat and bread are my food.

Answered the lion; “Your pride is the pride of one sated with food, therefore you don’t discern between your honor and your disgrace. Shall I be like you, bound with chains? Better for me to be without a ruler and skinny than to be bound to the table of others.”

Horse sense. A fellow once went to Reb Meir of Premishlan for advice about a competitor who was robbing him of his livelihood.

“Have you noticed that when a horse goes to the river to drink, it strikes its hoof against the bank?” the rebbe began. “When the horse bends its head, it sees its face reflected in the water. Thinking it’s another horse, it stomps, hoping to scare the other away and preserve the water for itself. But the horse’s fear is groundless — the river can water more than one horse.

“You are like this horse. You imagine that the river of God’s bounty cannot sustain both you and another, so you’re stomping your hooves to scare away an imagined competitor. You cannot guarantee your own success; all you can do is maximize your chances. Run your business as wisely as you can and know that whatever comes to you is decreed in heaven. Your only true competition is the reflection of self you see in the river.”

Rabbi’s advice. Living in a crowded, busy, noisy hut with his expanding family, a despairing man turned to the rabbi for help.

“Bring in the chickens,” the rabbi counseled. On another day, “Bring in the goat.” Then, “Bring in a cow.”

Now along with the more crowding, bustle, and clamor, there were clucking birds, an uncontrollable goat, and a trampling cow.

“Rabbi! It’s worse than a nightmare!”

“Send the animals out,” he counseled. That night, the man and his family slept soundly in the roomy, peaceful, quiet little hut. It could always be worse.

Literature to share

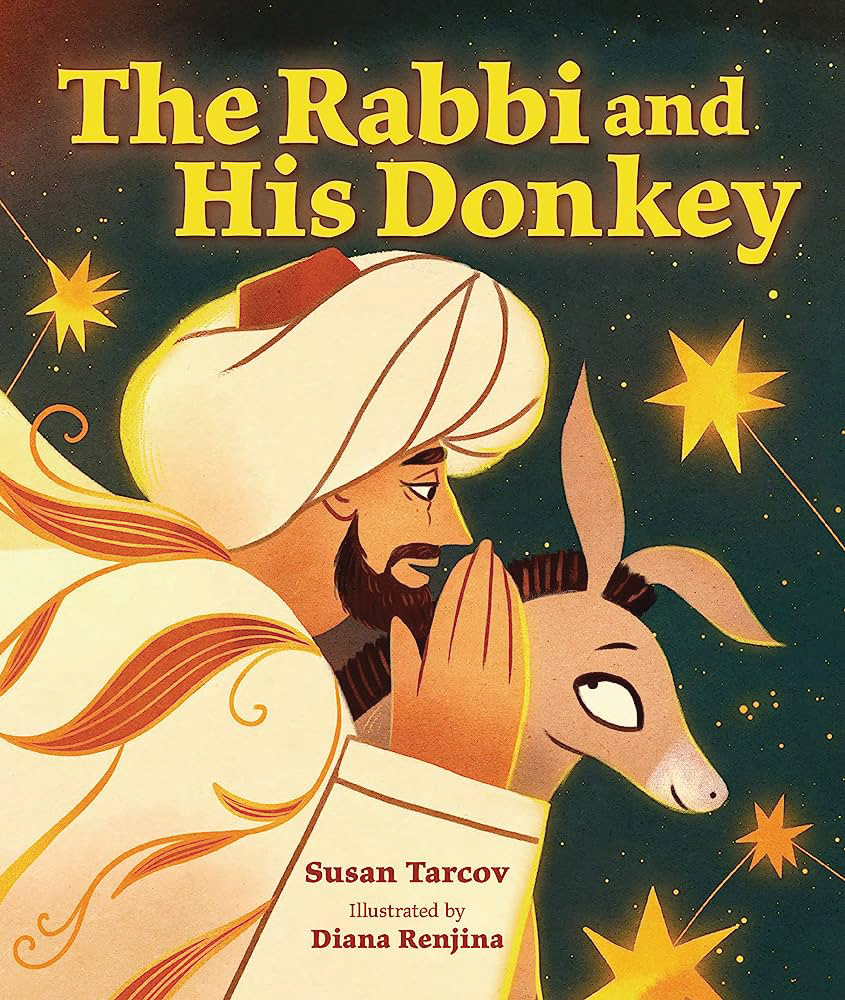

The Rabbi and His Donkey by Susan Tarcov. Every day, the great Rabbi Moses ben Maimon traveled to visit the Sultan in Cairo, according to his diary. While riding his donkey, he would think aloud, and the donkey listened and learned. But the journey was long—would a horse be better? Fittingly illustrated in the ancient arabesque style of the region, this children’s picture book shares some of Maimonides’ ideas as well as a lesson he learns from his donkey.

The Other Family Doctor by Karen Fine. Despite an allergy to cats, Karen Fine always knew she wanted to be a vet. Inspired by her grandfather, Oupa, a compassionate doctor who paid house calls to his human patients, Fine keeps the importance of understanding her patients’ stories — both animal and human — at the forefront of her care. Woven throughout the memoir are tales of her own pets, the animals she has treated, and the lessons they have taught her.

To read the complete July 2023 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.