They fought for the Union

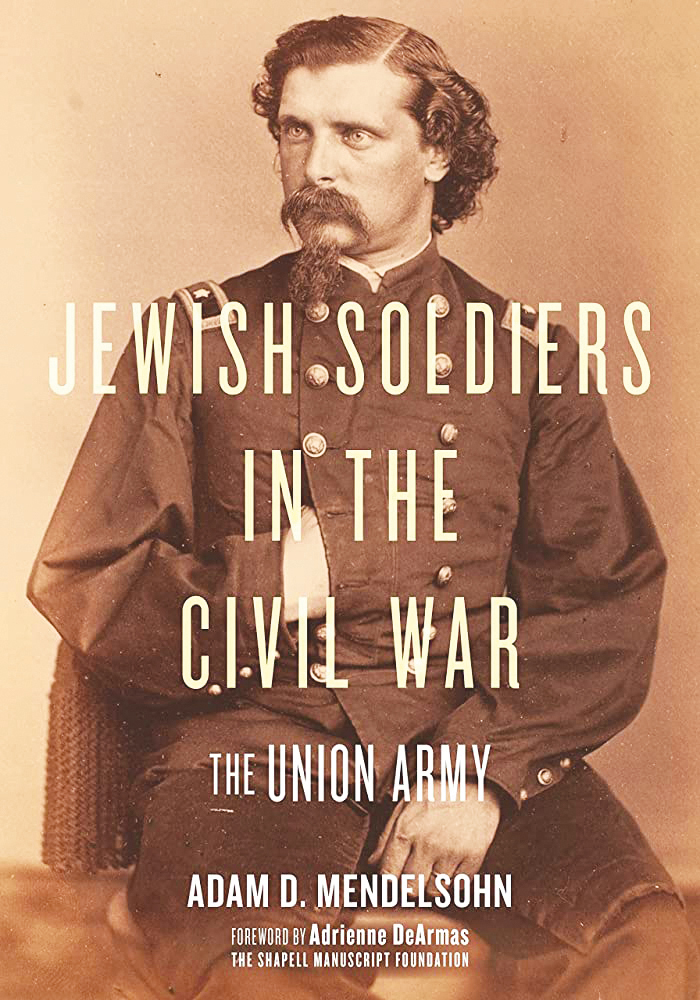

Jewish Soldiers in the Civil War: The Union Army • By Adam D. Mendelsohn • New York Univ. Press, 2022 • 323 Pages • $35

Book Review By Martin Gottlieb, Special To The Dayton Jewish Observer

The response of Jewish communities in the North to the Civil War was “tepid.”

That conclusion might surprise some. It is not the impression one gets from, say, the title of the 2014 book We Called Him Rabbi Abraham: Lincoln and American Jewry by Gary P. Zola. And it is not exactly support for the notion of American Jews as a reliable force for racial equality.

But it is the conclusion of a scholar who has studied a painstakingly collected database about Jews in the war. That database has been gathered by the Shapell Manuscript Foundation, an American and Israeli operation which collects historical documents, including letters.

In the 1890s, aspersions were cast in a prestigious journal, the North American Review, upon the role of Jews in the war. They were described as shirkers. In response, Simon Wolf wrote The American Jew as Soldier, Patriot and Citizen in 1895. He came up with 8,000 names of Jews who fought. Subsequent research revealed that some of those men weren’t Jewish and that Wolf missed some soldiers who were.

So the Shapell people set out to systematize the pursuit of information about who fought, but also about what their experiences were. Since 2009, a team of researchers there has been putting together a digital archive about the soldiers, including some who hadn’t previously been identified.

In 2017, Shapell asked Adam Mendelsohn, who had written other books on Jewish history, to study the foundation’s collections and to write a book about the Union army and then another about the Confederate army.

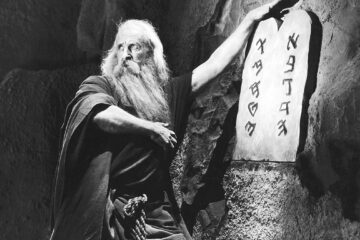

The result is an academic book, not very long and leavened with lots of photos, original letters, and documents. Mendelsohn writes as if a dissertation-approval committee looms with questions about whether he has pursued every issue as far as he could, even if an issue isn’t intriguing and even if he wasn’t able to offer a conclusion about it.

Still, there’s good stuff here, and the depth of his knowledge and his intellectual integrity cannot be questioned.

For starters, one must know that nearly all Union soldiers enlisted, as opposed to being drafted, though some enlisted only when threatened by the draft, which was created halfway through the war.

Jews did not enlist in high percentages. Mendelsohn says in Ohio, only 190 Jews out of a population of 9,000 enlisted, whereas more than 10 percent of all Northerners served.

One reason for the low Jewish rate was that many Jews lived in communities where opposition to the war was intense: New York, Baltimore, Cincinnati. And Jews tended to take on the politics of their surroundings.

Another reason was antisemitism. Very early in the war, complaints started to arise about the quality of equipment and clothing being sold to the army. The word shoddy was a noun, referring to a type of fabric that was not strong enough for combat uniforms. The cry went up that the people selling shoddy to the army were Jews, and the word shoddy became a part of everyday discourse.

Another apparent manifestation of antisemitism: Early in the war, rabbis were not allowed to be chaplains. That led to some hard feelings among Jews.

And there was this: In 1862, Gen. Ulysses Grant simply banned Jews from a vast area he controlled. His charge was that Jews were engaging in illicit trade with the enemy, helping cotton sellers find markets, for example, and thereby helping the Southern economy. His order meant that some Jews would actually have to leave their homes.

Lincoln overruled Grant almost immediately. But many Jews understood that Grant’s order grew out of prejudices that were widespread in the army. Mendelsohn says that Grant used the word Jew all the time to refer to the violators of his policy, presumably without knowing whether they were actually Jewish. That was not uncommon.

The word Jew sometimes seemed to refer to a category of people identified by behavior rather than religion.

Another factor presumably limiting Jewish enlistment was religious practice. Keeping kosher was pretty much out of the question in the army. For one thing, pork was an ever-present staple.

For whatever collection of reasons, Jewish community organizations did not aggressively promote enlistment the way many other community organizations in the North did.

In that context, it’s worth noting that, according to Mendelsohn, there were no Jewish army units. Other historians have said there were at least a couple. Mendelsohn says this confusion arises in part from the fact that some Jewish community groups did help to create army units (as did non-Jewish organizations).

But, he says, these weren’t Jewish units. It would have been difficult almost anyplace to put together a Jewish unit. Besides not being all that gung-ho, Jews just weren’t numerous enough, at about 125,000 in the Northern population of 19 million. And they were scattered.

Half the Jewish population lived away from the big cities, and most units were formed regionally. That meant a Jew might find himself alone in his unit as to religion.

Getting beyond the numbers — an announced goal of both the foundation and the author — the book focuses on the stories of specific Jews. These are not generally war stories: What was it like out there under fire? They are stories about what life was like in camp and in the military generally, and about why a guy volunteered.

One remarkable phenomenon: Some of the Jewish soldiers first arrived in this country during the war. They were young men who spoke little English and had difficulty finding jobs in a troubled economy. The army was a job.

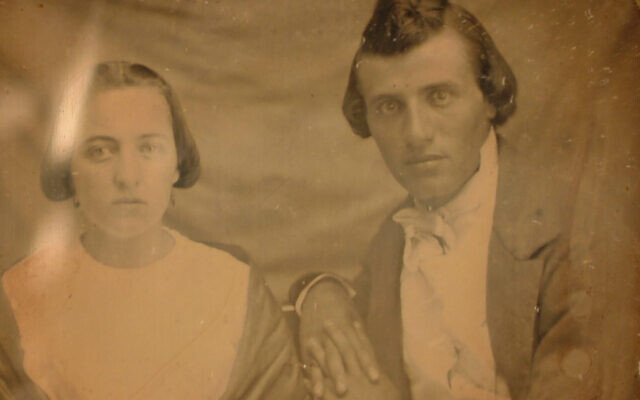

Others had been here a while. One memorable story from Ohio involves the Spiegel family, as in the eventual mail-order company. They were from Millersburg in Holmes County near Cleveland. The territory was deeply Copperhead, that is, anti-war. Marcus Spiegel joined the army because he was in financial trouble and could get his debts ameliorated for joining, while earning a decent income.

In keeping with the Christians in his community, he was appalled by the idea of a war for abolition. “I do not fight or want to fight for Lincoln’s Negro Proclamation one day longer than I can help.” But as time passed, his views changed. He became anti-slavery and pro-Lincoln.

Spiegel rose to the well-paying rank of lieutenant colonel and developed a taste for command and for army life, thus frustrating his Quaker wife. At a certain stage, Spiegel hired his brother Joseph, a civilian, as sutler to his unit. A sutler was a sort of traveling merchant with a general store, serving the troops. Ultimately, Marcus died of a combat wound, and Joseph went on to form the catalog company in Chicago.

Mendelsohn doesn’t get much into what Jews in general thought about slavery. This presumably reflects that the issue isn’t mentioned much in the letters he’s read. He does record that some Jewish soldiers were always motivated to fight against slavery. But he clearly communicates that most Jews in the population were not. For one thing, he notes, many in the North feared that emancipation could result in freed slaves competing for jobs in the North. And he notes that Jews were as likely to have their own prejudices as anybody.

As for anti-Jewish prejudice, some Jewish soldiers were bedeviled by it. Most were not. Many hid their Jewishness by changing their names. But even among men who were openly Jewish, it wasn’t necessarily a big problem.

Actually, before the Civil War, antisemitism was not a very public force in the United States. In those days, anti-immigrant feeling was largely focused on the Irish and on non-Jewish Germans, both being much larger, more visible populations than Jews.

But the stereotypes were in place, if somewhat dormant, and the war brought about all manner of bad things for which somebody had to be blamed.

Testing Medal of Honor recipients’ mettle

Mendelsohn’s book lists the handful of Jews who won the Medal of Honor in the Civil War. Among them is David Urbansky (under various spellings). Born in Prussia, he arrived in the United States four years before the war. He served for almost the entire war, seeing many battles. He was in the 58th Ohio Infantry, a German-speaking unit.

After the war, he established a clothing store in Piqua. He and his wife had 12 children. He lived until 1897 and was buried first in Piqua’s Jewish cemetery, then reinterred in Cincinnati, where the American Jewish Archives has his medal.

Urbansky’s medal is unusual. Instead of referring to a specific date – the way the others do – it refers generally to battles at Shiloh and Vicksburg.

Author Mendelsohn is not a big fan of the Civil War Medal of Honor. He says 1,500 were given. He doesn’t note this, but the medal back then didn’t say anything about behavior “above and beyond the call of duty,” today’s wording. The medals then referred to “extraordinary heroism.”

The reverse side of Urbansky’s medal refers to “gallantry.” Mendelsohn says the criteria were “subjective and imprecise, and some recipients…nominated themselves.”

He tells the story of another Jewish honoree, Leopold Karpeles, whose account of the relevant events in his case was later challenged in the regiment’s history. Karpeles nominated himself and got letters from his commanding officers acknowledging his bravery and general conduct, but in general terms, not in reference to a specific engagement. He received the award two weeks later.

Mendelsohn offers no such details about Urbansky.

Retired Dayton Daily News editorial writer Martin Gottlieb is the author of Lincoln’s Northern Nemesis: The War Opposition and Exile of Ohio’s Clement Vallandigham. He is also the advisor to The Dayton Jewish Observer.

To read the complete April 2023 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.