It’s personal.

By Rabbi Cary Kozberg, Temple Sholom, Springfield

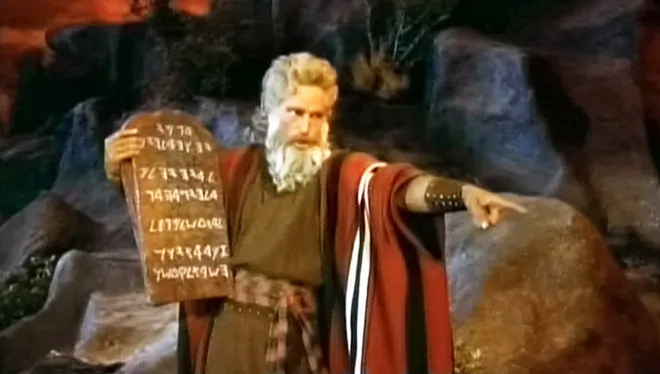

I admit it. Since I first saw it as a kid, I have been a devotee of the 1956 film The Ten Commandments. Even as I came to realize the extreme liberties it takes with the biblical account (inaccuracies), what continues to recommend it is its reiteration of the biblical message that God wants human beings to be free.

But not just free. Free to serve Him: “Let My people go, that they may serve Me (Ex. 7:27).” That’s why it’s a bit curious that in the film, Moses (Charlton Heston) relays only the first part of God’s directive to Pharaoh (Yul Brynner) — “Let My people go”— but leaves out the second part, “that they may serve Me.”

Indeed, because the quote is often invoked without this second part, there is a common misconception that the story of the Exodus from Egypt is only about freedom from slavery, when more correctly it is about freedom to serve God.

Fortunately, this curious deletion is corrected later in the film. When Moses comes down from Mt. Sinai with the Tablets and begins to scold the people for worshipping the Golden Calf, he is confronted by Dathan (Edward G. Robinson) who says to him: “We’re gathered against you, Moses. You take too much upon yourself! We will not live by your commandments. We’re free!”

To which Moses replies: “There is no freedom without the Law.”

As I write this, we are celebrating Pesach/Passover. One of the other names of Passover is z’man cheruteynu, the season of our freedom.

But taking a cue from Moses’ response to Dathan (an exchange that doesn’t occur in the biblical text), the “season of our freedom” is not really limited to the week of Passover.

Rather, it encompasses the seven weeks which begin with Passover and culminate with Shavuot, also called z’man matan torateynu, the season of the giving of our Torah.

Unfortunately, these two holidays are often misunderstood as two distinct festivals that commemorate two distinct events.

More correctly understood, the holidays and the events that they commemorate are inextricably connected. Why? Because the movie script is correct: There is no freedom without the Law.

Law creates clear boundaries and prevents social chaos by legislating what is and is not acceptable behavior when people live together.

Without laws, people tend to believe Dathan’s words: “freedom” is having the right to do whatever they want to do whenever they want to do it.

They confuse freedom with license. Significantly Judaism’s source of Law, the Torah, hardly discusses what rights people have. On the other hand, it clearly sets forth an extensive list of responsibilities: 613 of them.

On Shavuot — the season of the giving of our Torah—we affirm that we were not just freed from slavery, but liberated to serve God.

We commemorate gathering at Sinai, hearing the Voice that addressed us as a people and collectively we responded “na’aseh v’nishmah”—we will comply and listen/understand, agreeing to comply first and understand later.

During the Passover Seder, we tell the story of our liberation as a people. But we are also encouraged to experience that liberation personally: In every generation each person should see him/herself as if they themselves went out of Egypt.

On Shavuot, we recall our collective experience of hearing God’s Voice at Sinai and receiving the Law by which to realize true freedom.

However, just as the collective event of leaving Egypt is supposed to be experienced by every person individually, our tradition seems to encourage the collective event at Sinai also be experienced by every person individually.

Indeed, not only are we taught that every Jewish soul past present and future heard God’s Voice at Sinai, but also that every person heard the Voice according to his/her individual understanding.

The Voice was/is addressed to us as a people; but it was/is also addressed to us as individuals.

As the Haggadah’s directive encourages us to experience liberation personally, so Shavuot calls us to experience the revelation at Sinai personally.

It calls each of us to remember/imagine what it was like at Sinai when we were there. It calls each of us to ask: Where did I stand? Next to whom was I standing? What did I see?

And perhaps most importantly, to ask: In addition to what I heard as a member of the Jewish people, what did I hear as an individual?

Unfortunately, although Shavuot is arguably the most important Jewish holiday (without the Torah, there would be no other holidays), it is also the most neglected.

Nevertheless, even if it is not observed as Jewish tradition mandates, one need not neglect it altogether.

Shavuot beckons each of us to reflect upon what it means to each Jew to be a committed Jew and to renew that commitment on this important anniversary.

It beckons each of us to ask again: What did I hear at Sinai? What assignment was I given, and am I fulfilling it to the best of my ability?

Paraphrasing a famous line from another blockbuster film, I pray that on this Shavuot, each of us will understand that our commitment is “not just business; it’s personal.”

To read the complete June 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.