100 years ago, young Black, Catholic & Jewish leaders legally kept the Klan from rallying at Memorial Hall

UD law professor on why it couldn’t happen today, how & why the U.S. Supreme Court raised the free speech bar

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

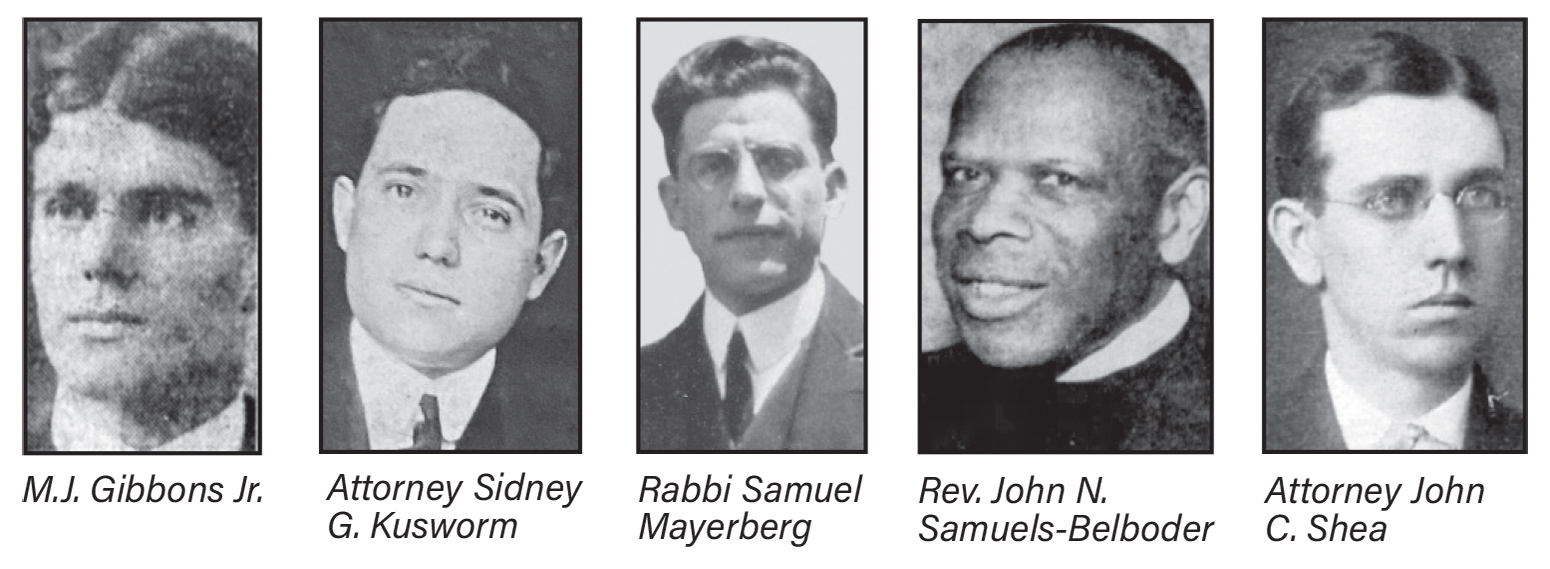

Though they were all in their 20s and 30s, the five young men were already well-respected in their professions and for championing social justice causes in Dayton.

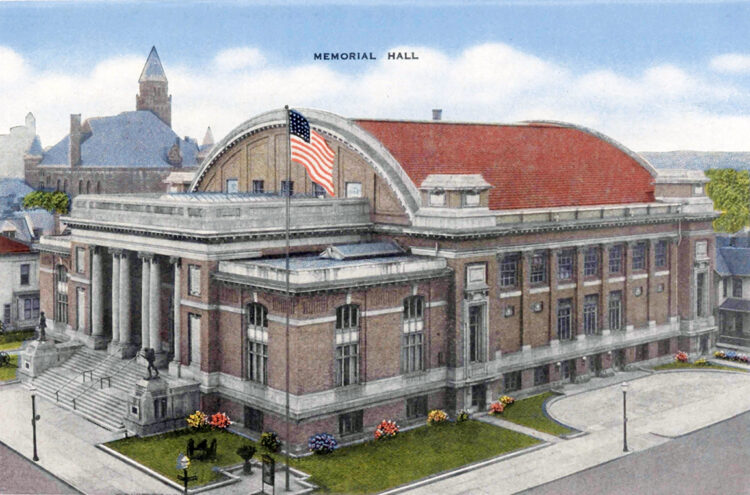

Ohio was a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity when the young men joined together on May 26, 1922 to file an injunction and prevent the Klan from presenting a speaker for an invitation-only event that evening at Memorial Hall, then as now, Montgomery County’s war memorial facility.

The Dayton Daily News informed its readers it brought to the attention of the Montgomery County commissioners that the county had allowed the Klan to book the meeting.

The Klan program was billed as a speech on Americanism by Billy Parker of Branson, Mo. Parker was the editor of the New Menace, an anti-Catholic newspaper.

The organizer of the event, C.L. Harrod, “King Kleagle” of Columbus, had already been prevented from presenting Parker in Akron because of a court injunction.

Although Montgomery County’s commissioners claimed they weren’t aware Memorial Hall had been rented to the Klan, Harrod boasted to the Dayton Daily News that there will be “no interference.”

“We have some of the most prominent city officials and citizens…enrolled in our membership. They have assured us that nothing can stop our meetings. We will have no more interference.”

The commissioners didn’t cancel the meeting. The five young men filed an injunction to bar the Klan from holding the event not only at Memorial Hall but anywhere in the county, as the lecture to be given “will provoke and incite riot and disorder within the City of Dayton and County of Montgomery and religious prejudice and hatred among the people thereof and may and will result in great and irreparable injury to person and property of the citizens of this county and state.”

A county judge granted the injunction hours before the scheduled event. Memorial Hall was locked up, and the Klan instead held its program that night at a high school in Greene County.

The young men behind the injunction were Temple Israel’s Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg; civic and business leader M.J. Gibbons Jr., a Catholic; and the Rev. John N. Samuels-Belboder, pastor of the African American St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church. The attorneys who prepared the injunction were active in civic affairs as well as with their respective religious communities: Sidney G. Kusworm, a Jew; and John C. Shea, a Catholic.

In Ohio, the Klan’s main targets for hatred were Black people, Catholics, and Jews.

In Ohio, the Klan’s main targets for hatred were Black people, Catholics, and Jews.

The plaintiff Kusworm and Shea named in the case was Edward T. Banks, 48, an African American clerk with the municipal court. Banks was known for his speeches about the progress African Americans had made in business and professional fields.

“Back then, states could block something like the KKK rally, both because we didn’t really think the First Amendment applied to the states at all, but also because even First Amendment juris prudence applied to the federal government was fairly impoverished as compared to now,” explains University of Dayton Law Prof. Erica Goldberg, who teaches torts, constitutional law, and criminal procedure. She also blogs at inacrowdedtheater.com about free speech values.

“My personal view about this is that Jews have to be vigilant about antisemitism and they have every right to be concerned for their safety, but we’ve also been on the forefront of protecting freedom of speech as an important principle/value regardless of the speaker. And often, because we find the speakers’ views really offensive, that really shows commitment to the principal.

“So sometimes these interests can be intentioned and not everyone agrees on whether or not where we’ve landed is correct, but certainly Jews have been on both sides of the issue, both wanting to prevent KKK rallies and hate group gatherings, but also wanting to protect their right to freedom of speech.”

At the time of the injunction, in 1922, the First Amendment had not yet been incorporated against the states, Goldberg says.

“The First Amendment, technically, if you look at the text, only applies to Congress, meaning federal action,” she says. “Of course, that’s no longer the case. Now, the First Amendment applies to anything a state actor would do, a governor would do, a state legislature would do as well.”

Prior to 1925, the year when the First Amendment started getting incorporated against the states, Goldberg says, “there was little states could not do” when it came to censorship.

“Basically, all of the First Amendment litigation was happening because of congressional action. And then, even once the First Amendment got incorporated against the states, it was a much less robust conception of free speech than we have now.”

Goldberg says the First Amendment started picking up some traction in cases with U.S. Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes’ famous 1919 dissent in Abrams v. United States, in which he argued, “It is only the present danger of immediate evil or an intent to bring it about that warrants Congress in setting a limit to the expression of opinion where private rights are not concerned.”

It still took until 1969 for the First Amendment to develop the strong protections of freedom of speech we have today.

That Supreme Court case, which sets our modern incitement standard, Goldberg says, was Brandenburg v. Ohio.

“A Ku Klux Klan member was convicted under this statute called the Ohio Criminal Syndicalism Statute,” she says. “The Supreme Court set out the incitement standard because it wanted to distinguish between what it calls mere advocacy and incitement to imminent lawless action. We cannot punish advocacy. Even if it’s advocacy for something detestable. And so the more general, the less imminent some statements are — or their reason for a group’s gathering — the more likely it is to be protected. So that current incitement standard is: Your speech can only be regulated as incitement if it’s directed to and reasonably likely to produce imminent lawless action.”

The government, Goldberg says, is allowed to create content-neutral time/place/manner restrictions. “You could start controlling when gatherings happen in public spaces or how loud they’re allowed to be,” she explains. “But what you’re not allowed to do is discriminate on the basis of the content of them. So if you have a mechanism for allowing organizations to assemble, for allowing groups to march, you just have to apply that evenhandedly. You can’t discriminate on the basis of viewpoint for protected speech.”

Getting back to Dayton in 1922, Goldberg doesn’t wonder at what now appears to be the stretch in the injunction’s wording that the KKK event would “incite riot and disorder.”

“The standards just were applied very differently back then,” she says. “Usually instead of the current incitement standard — the Brandenburg ‘clear and present danger’ standard — then they would say that people publishing pamphlets opposing World War I presented a clear and present danger. So even if they paid lip service to some sort of speech-protected standard, it often just wasn’t applied in a very speech-protective way. And that’s really different than now.”

To read the complete May 2022 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.