A mystery of U.S. Jewish history with Dayton ties

Caterer for the banquet that divided American Judaism in 1883 is buried at Temple Israel’s Riverview Cemetery.

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

It’s no exaggeration to say that the person who set in motion the contours of American Judaism we know today is buried at Temple Israel’s Riverview Cemetery.

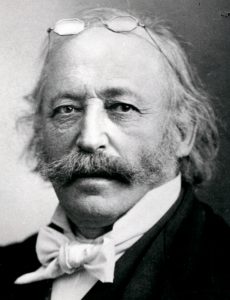

In 1883, when Prussian-born Jew Gustave “Gus” Lindeman was a celebrated caterer in Cincinnati, Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise hired him to prepare the banquet to celebrate Hebrew Union College’s first rabbinic ordination ceremony and the Union of American Hebrew Congregations’ 10th anniversary — both of which Wise founded.

Wise, the architect of Reform Judaism in America, hoped to unite American synagogues and rabbis within a broad coalition that would bring traditionalists and reformers together.

More than 100 rabbis and layleaders from 76 Jewish congregations around the country showed up for the July 11, 1883 ordination ceremony at Wise’s Plum Street Temple. From his base in Cincinnati, Wise was on the edge of uniting American Judaism.

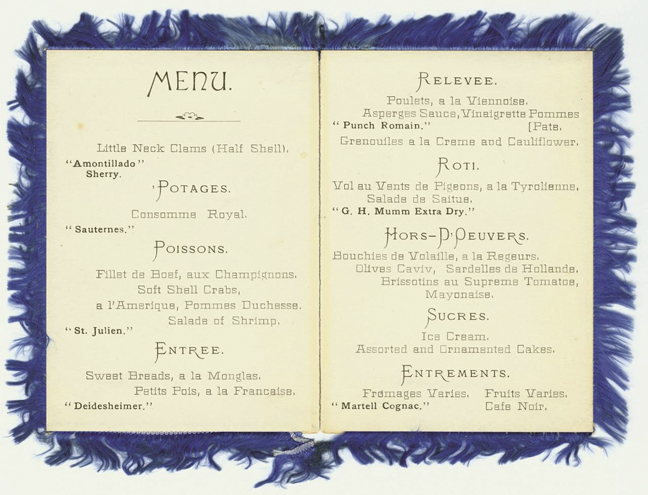

But at the banquet, held afterward at the Highland House on Mt. Adams, Lindeman served a treyf (unkosher) menu, albeit without pork.

No one knows for certain whether it was Wise or his committee who approved the menu, or if Lindeman acted on his own, though it’s unlikely Wise would intentionally provoke his guests when his aim was to bring them together.

Cincinnati’s Reform German Jews did tend to eat treyf, except for pork. But as a result of the “Treyfa Banquet,” outraged traditionalists would go on to establish Orthodox and then Conservative Judaism.

A popular caterer

Lindeman was born in 1845 in Prussia. He first showed up in Cincinnati’s city directory in 1867 as a barkeeper in a saloon.

By the 1870s, Cincinnati newspapers described him as a fashionable, popular caterer.

When Cincinnati’s German-Jewish Allemania Club opened its new building at Fourth Street and Central Avenue on May 1, 1879, Lindeman catered the event.

The Cincinnati Enquirer described the opening as “one of the most brilliant social events of the season,” and “one of the most enjoyable affairs that has ever been celebrated in this city.”

Among the 350 guests was Ohio Gov. Richard Moore Bishop. Over the music of an orchestra, Lindeman’s dinner for the “Hebrew society” included oysters, various meats, and vanilla ice cream — all violations of kashrut — but no pork.

After the 1883 Treyfa Banquet, when the more traditional delegates returned to their homes, they spread the word about the debacle through Jewish and even general newspapers. One account in a Jewish newspaper was written by Henrietta Szold, there with her father; she would later found Hadassah, the women’s Zionist organization.

In Wise’s English-language publication, The American Israelite, he blamed the error on Lindeman. However, in his German-language publication Die Deborah, he wrote that it was the committee that ordered the meal.

In a Jan. 16, 2018 essay for JTA, Brandeis University Prof. of American Jewish History Jonathan Sarna wrote that Wise knew the banquet was a blunder, but Sarna highly doubted that Wise was to blame.

“After all, he himself kept a kosher home — his second wife, the daughter of an Orthodox rabbi, insisted upon it,” Sarna explained. “But he was not the kind of leader who believed in making apologies. Instead he lashed out against his critics, insisting that the dietary laws had lost all validity, and ridiculed them for advocating ‘kitchen Judaism.’”

Line in the sand

In 1885, the Reform movement codified its eschewal of Jewish dietary laws in Article Four of the Central Conference of American Rabbis’ Declaration of Principles, known today as the Pittsburgh Platform:

“We hold that all such Mosaic and rabbinical laws as regulate diet, priestly purity, and dress originated in ages and under the influence of ideas entirely foreign to our present mental and spiritual state. They fail to impress the modern Jew with a spirit of priestly holiness; their observance in our days is apt rather to obstruct than to further modern spiritual elevation.”

Wise, who also founded the CCAR, presided over the meeting. His line in the sand led American Judaism to splinter into two and later three movements.

Traditionalists established the Jewish Theological Seminary in New York in 1886; two years later, they established the Union of Orthodox Jewish Congregations of America.

JTS and the Orthodox Union eventually parted ways in the years after Rabbi Solomon Schechter arrived from England to lead JTS in 1902. JTS would become the flagship institution of the Conservative movement.

Making a name in Dayton

Lindeman moved to Dayton in 1895, where he lived until his death in 1927. He made a name for himself as the steward of the Dayton City Club, a non-Jewish social club at the southwest corner of First and Main Streets.

A 1902 ad in the Dayton Daily News for Rising Sun Baking Powder is centered around a testimonial from Lindeman in his role as the Dayton City Club’s steward.

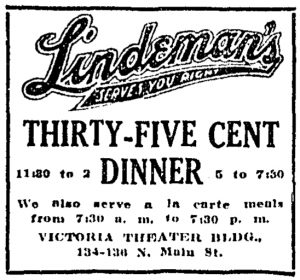

Around 1909, Lindeman struck out on his own, opening Lindeman’s restaurant and catering business in a storefront at the Victoria Theater.

Among his catering clients was A.M. Kittredge, president of the Barney & Smith Car Company.

The Great Flood of 1913 and its damage to the Victoria Theater marked the end of Lindeman’s restaurant.

He managed at least one more restaurant, Maharg’s, and continued his catering business from his home, 49 W. Holt St., until 1925.

But his contributions to Dayton and its Jewish history don’t end there.

His granddaughters, sisters Josephine and Hermene Schwarz, founded the Schwarz School of Dance in 1927 and the Experimental Group for Young Dancers in 1937 — later renamed the Dayton Ballet — the second-oldest ballet company in the United States.

Would American Judaism have ended up splintering had there been no Treyfa Banquet? Most likely. But Lindeman’s most famous meal is what set it in motion.

Marshall Weiss, editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer, is the author of Jewish Community of Dayton (Arcadia, 2018)

Related: DCDC at 50: Celebrating the Schwarz sisters’ influence

To read the complete September 2018 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.