Transferring pain to pages

Robert Kahn didn’t want to revisit memories of Nazi Germany. He had to.

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

To a generation of Dayton-area schoolchildren, he is known as the boy the Nazis forced to play the violin on Kristallnacht while they beat his father with clubs, ransacked the family’s apartment, and burned their possessions.

But Robert Kahn would also go on to work for Operation Paper Clip — the secret U.S. intelligence and military program that brought German scientists to work for the U.S. government at the end of World War II.

Kahn, who has never spoken publicly about Operation Paper Clip, will discuss the emotional challenges he faced on the project, when he delivers the keynote speech for this year’s Greater Dayton Yom Hashoah Remembrance, on April 23.

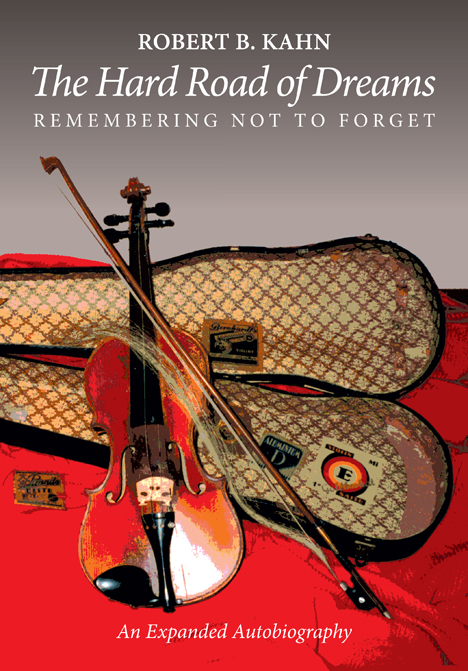

His reflections on Operation Paper Clip are also detailed in his newly-published encyclopedic autobiography, The Hard Road of Dreams: Remembering Not To Forget.

With Kahn’s burden — to carry so many painful memories — now transferred to the printed page, the 93-year-old says he feels tremendous relief.

“The entire area is very difficult for me to talk about,” he says of his family’s situation in Nazi Germany. Though he, his parents and sister ultimately managed to escape, 18 members of their family did not.

“It’s very sad,” he says. “I’ve made an effort throughout my life, especially with the family — my wife, Gertrude, my children, my grandchildren — to talk as little about it as I could.”

But his children and grandchildren kept asking him for details.

“(Writing) gave me the ability to share it, and then close the book,” he says. “It’s not good to keep those memories alive in the way that you deal with it on a daily basis. My sister did that, and she passed away because she could not live her life without, on a daily basis, thinking about the past.”

An ‘autopsy’ on himself

It took Kahn 27 years to write his autobiography. He describes the process as “performing an autopsy” on himself.

“I have to use that term because that’s what it really is, and that’s what it felt like.”

After Kahn made his way to the United States, he fought with the U.S. Army Air Forces in the Pacific and then attended the University of Oklahoma. While living in Chicago, in 1946, he saw a newspaper ad looking for people who knew technical German. He responded and was assigned to work in army intelligence at Wright Field.

“And that job, it turned out, was Operation Paper Clip,” he says. “It was top secret. It had to do with German scientists that were brought over for picking their brains in regard to what they were doing. My job was to interrogate some of them.”

Of the more than 1,600 German scientists brought to work for the U.S. government through Operation Paper Clip, 86 aeronautical engineers were sent to Wright Field. The aim of Operation Paper Clip was to gain military advantages over the Soviet Union in the Cold War, and later on, in the space race.

“I hated those guys, and it was kind of difficult to work with them and not show my dislike for them and the work that they did,” Kahn recalls. “I found out much about the scientific experiments they had performed using human beings as test vehicles. And these test vehicles were, in most cases, Jews.”

The German scientists didn’t talk to Kahn about those experiments; he read about them in the captured documents that were available to him.

He says their experiments in Nazi Europe were carried out to determine the ability of pilots to withstand extreme conditions such as hypothermia and submersion in water.

“Many of the test subjects never made it through the experiments,” Kahn says.

“There were a number of situations that I got involved in that caused a lot of embarrassment to me, because of their attitude that came about at certain occasions,” he says.

Once, when he heard a few of the scientists complain in the cafeteria at Wright Field about the quality of the food — comparing it to the food they were used to in Germany — he picked up their trays and put them on the conveyor belt to the kitchen.

“I was so emotionally involved that it was very difficult for me to let that conversation go by,” Kahn says. “Of course they complained, and I was called to the front office and got a dressing down.”

After two years, and with most of the scientists sent to other locations, Kahn transferred to work on the base in procurement and resources. He retired from Wright-Patt in 1985.

Even after his work on Operation Paper Clip, Kahn says he was conflicted in his jobs at the base.

“I didn’t like the work that I was doing because of the nature of the work, which dealt with creating an organization dedicated to defense, and this meant vehicles that would go out and kill people. Having been through the Holocaust and the war, this was not my forte,” he says.

“But in order to make a living, I did the best I could under the circumstances, and tried to do as good a job as I could.”

He says he never talked about Operation Paper Clip because of the government’s requirement to keep everything secret.

“In the book, I only touch the surface of the work that I was doing,” Kahn says. “I could not go into specifics. And yet, you will get the sense of the kind of work and the strain on me to perform under those circumstances.”

For his autobiography, Kahn also conducted meticulous research on his 18 family members who were murdered in the Holocaust.

“It was very important to me that I find out as much as I could about them, at least in their final hours,” he says. “Otherwise, their names would be lost, their lives would not be remembered, and my children and grandchildren would never know about it.”

A reluctant speaker

Kahn didn’t speak publicly about the Holocaust until his later years, because of an incident when he first arrived in the United States.

“I was invited by a lady that belonged to Temple Sinai in Chicago to come for services and join for the Oneg,” he says. “She asked me to talk to people about what was happening in Germany. And so I did. After a while, this lady who had invited me came to me as I was talking to a few people and said, ‘Bob, don’t talk about this anymore. You’re spoiling everybody’s evening.’

“It upset me so much that I decided not to speak about it anymore. And that reflected the attitude of many people: because what was going on in Germany, in Europe, was so terrible, people couldn’t understand it, weren’t sure that it was truthful. It was so upsetting to them — including many Jews.”

Kahn changed course about 25 years ago, when the caretaker of the house where he used to live in Mannheim sent him the violin from his youth; it had been hidden in the house all those years.

Kahn changed course about 25 years ago, when the caretaker of the house where he used to live in Mannheim sent him the violin from his youth; it had been hidden in the house all those years.

That violin, which Kahn was forced to play on Kristallnacht, is on display with the Prejudice and Memory Holocaust exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Kahn used to speak to thousands of middle and high school students each year when they visited the exhibit, and at their schools.

These days, though, he’s gotten away from talking to groups.

“If affects me so much,” he says. “I can do it once in a while, but not too often.”

That’s why he began writing the book 27 years ago. When someone asks him questions, he can now point to the book.

“When you talk about it, it comes back to life.”

Robert Kahn is the keynote speaker for the Greater Dayton Yom Hashoah Remembrance, at 4 p.m. on Sunday, April 23 at Temple Beth Or, 5275 Marshall Rd., Wash. Twp. Max May Memorial Holocaust Art Contest entries will be on display beginning at 3 p.m. For more information, call Jodi Phares at 610-1555.

To read the complete April 2017 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.