The fight for freedom continues

By Rabbi Judy Chessin, Temple Beth Or

Our feet “prayed” as 20 Jews from Dayton marched across the famous Edmund Pettus Bridge in Selma, Ala. This was just one of many stops on our Etgar 36 Civil Rights Journey in February, on which Dayton high school students participated with me, Temple Israel’s Rabbi Karen Bodney-Halasz, and three adult chaperones: Sean Frost, Barb Cauper Mendoza, and Adrianne Miller.

Etgar 36, an organization that sponsors educational civil rights excursions throughout the country, led us on a life-changing journey, which was generously subsidized by a Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton Innovation Grant, Temple Beth Or, and Temple Israel. The overall itinerary included many sites such as the Rosa Parks Museum, the Civil Rights Memorial Center at the Southern Poverty Law Center, Birmingham’s Civil Rights Institute, Atlanta’s AIDS Memorial Quilt Project, and the Ebenezer Baptist Church. In each place, history came to life.

But no exhibit could possibly convey the power that we felt upon meeting living sources: the inspirational witnesses who described their own personal plights and heroism during the 1960s civil rights battles in our nation’s deep South.

In Selma, Ala., we met Joanne Bland, who lined us up on a tiny, cracked patio behind Brown Chapel African Methodist Episcopal Church.

She reminded us that we were standing in the footsteps of history. From this very spot, Bland and her friends from SNCC, the Student Nonviolent Coordination Committee, headed out on their historic trek over the Edmund Pettus Bridge and on to Montgomery to demand voting rights which had been denied to African-Americans.

Bland, whose mother had died in a Selma hospital while awaiting the arrival of “black blood” for a transfusion, didn’t originally understand what it meant to fight for freedom. Hadn’t she learned in the third grade that Abraham Lincoln and the Emancipation Proclamation had already freed the slaves? And yet, every time she went downtown, she would peek through the window at the all-white lunch counter at Carter’s Drugstore and wish that she could spin on the stools and eat ice cream.

One day, Bland’s grandmother said to her, “You’ll be able to do that too one day…when we get our freedom.” And thus at the tender age of 8, Bland became a freedom fighter. By the time she was 11, she had already been arrested 13 times for participation in non-violent voting rights marches and prayer vigils.

Bland discussed in great detail how Selma became the battleground for voting rights in the United States. She still trembled as she described the violence on Bloody Sunday — March 7, 1965 — when state troopers and county law enforcement officials attacked unarmed marchers with billy clubs and tear gas.

After another unsuccessful attempt called Turnaround Tuesday, the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. obtained an injunction and the marchers were finally allowed to cross the bridge on March 21, 1965 guarded by the very police who had attacked them just days before.

Bland and her fellow civil rights activists lined up on that very patio behind her church. More than 3,000 people began the walk, traveling 12 miles a day, in the rain and the cold, sleeping in fields along the way, until they reached Montgomery four days later. By the time they marched up to the capitol building in Montgomery, their group had grown to 25,000.

As a result, fewer than five months later, President Lyndon B. Johnson signed the Voting Rights Act into law calling the day “a triumph of freedom as huge as any victory that has ever been won on any battlefield.”

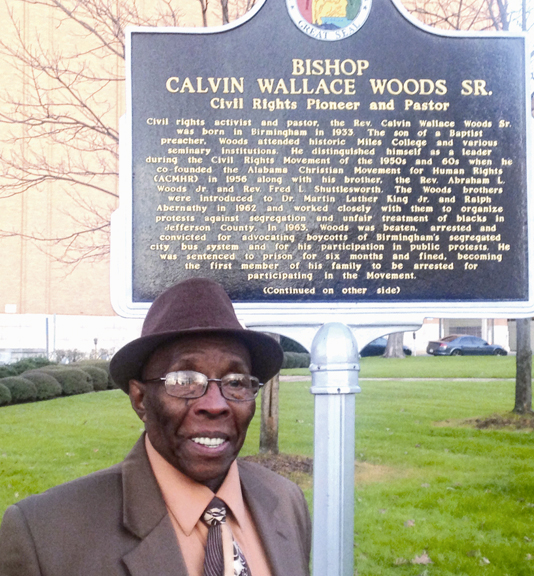

Another amazing civil rights hero we met was Bishop Calvin Woods Sr., an 82-year-old pastor in Birmingham.

A diminutive elderly gentleman, he surprised us with his mighty passion and sonorous voice. The bishop described how segregation had permeated everything in Birmingham. Even in the courts of justice, wherein witnesses were sworn in on the Holy Bible, there was one Bible for white witnesses and another Bible for black witnesses.

Woods worked with Baptist Minister Fred Shuttlesworth, one of Birmingham’s most prominent civil rights activists, to organize non-violent Birmingham protests against racial segregation and injustice.

Participating in these protests were hundreds of children, some as young as 6 years old.

Thousands were arrested and the marches persisted for several days. The Birmingham police commissioner, Eugene “Bull” Connor, ordered the use of fire hoses and attack dogs to suppress the protests. When images of children knocked unconscious by fire hoses, trampled and bitten by snarling dogs hit the media, many Americans were startled out of their apathy toward civil rights issues.

As we stood on the Kelly Ingram Park’s Freedom Walk, we again marched in the footsteps of those brave men, women, and children. And even though we only passed by sculptures of fire hoses aimed at us and through statues of snarling angry dogs lunging at us, it was nonetheless frightening. We could only guess at the terror and despair of the marchers.

Woods reminded us not to become complacent, for the battle is far from over. His hypnotizing call made us answer as one, even as he had rallied those young protesters half a century ago: “What y’all want?” Freedom! “When y’all want it?” Now! “How much y’all want?” All of it!

While these historic events occurred a half century ago, their message resonates among us today. Our teens were quick to equate these civil rights struggles with the inequities they see now: from gay rights to voter suppression, from sexual identity and gender equality issues to the battle for religious tolerance, from immigration concerns to the unrelenting racial inequities that persist in our nation to this day.

Our youngsters took Joanne Bland’s warnings to heart, “You’re the ones who have to make this world better for your babies. No one else is going to do it for you! Will you promise me, you’ll do it?” And they did.

In this Jewish season of Freedom, we recall that marching alongside the Rev. Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. from Selma to Montgomery, was Rabbi Abraham Joshua Heschel. It was Heschel who famously described the journey saying, “Even without words our march was worship. I felt my legs were praying.”

Dr. King and Rabbi Heschel met in January 1963 at the National Conference of Christians and Jews Conference on Religion and Race. There, Rabbi Heschel proclaimed: “At the first conference on religion and race, the main participants were Pharaoh and Moses. Moses’ words were, ‘Thus says the Lord, the God of Israel, let My people go that they may celebrate a feast to Me.’…The outcome of that summit meeting has not come to an end. Pharaoh is not ready to capitulate. The exodus began, but is far from having been completed.”

These words impressed King profoundly and he and Heschel became fast friends, so much so that the reverend had been planning to attend the rabbi’s family Passover Seder on April 12, 1968. Tragically, King never made it to that Freedom’s Feast. He was brutally assassinated eight days before Pesach, on April 4, 1968.

This year, as we gather around our Seder tables and condemn the bondage of slavery, I know that at least 20 Jews from Dayton will do so with renewed passion and insight. When we sing Let my People Go, it will have fresh resonance as we reflect upon this new, more contemporary freedom journey that we have undertaken.

The fight for freedom is as old as our people and as new as our nation. It is not just an ancient clarion call from generations past, it is likewise an abiding commandment and commitment for us in our own day. May we honor the promises we made to the heroes we met along our journey. This year, may we do our small share for the civil rights of all humanity so that we can together raise our voices: “We shall overcome!”

To read the complete April 2016 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.