Honest comfort

By Rabbi Shmuel Klatzkin, Chabad of Greater Dayton

Among the great comforts of this coldest and darkest season of the year is snuggling up with a good book.

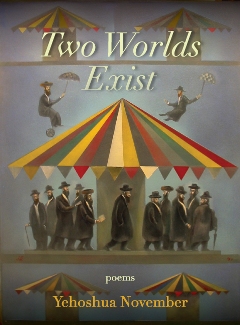

Not always does that mean we are turning to things we believe to be lofty. Comfort reading and dutiful reading mostly point us in different directions. But not always. Two Worlds Exist: Poems by Yehoshua November (Orison Books, 2016) is a wondrous exception.

There is much comfort in this small profound volume, but it is not cheap or easy comfort.

The words themselves are fresh and clean, plain-spoken language that does not tax the reader with pretension or needless obscurities.

It is rather that the poet brings his readers deep into the real mysteries of our own existences, the genuine struggles that real people experience every day, in privacy and dignity.

The real experience which the poet confesses is that of a profoundly religious man in a deeply traditional community.

Cliché would have it that such a person would have little in common with others who do not share his commitments. But his spiritual and artistic integrity shed all traces of cliché.

No membership card is needed to access his work, though it profoundly illuminates the shared Jewish experience so many of his readers bring. Teaching at Rutgers University and Touro College, November, like most of us, lives simultaneously in many worlds. His poems light up our shared lifelong endeavor to make a coherent whole, to find the underlying truth that unites our spirit, our mind, our emotion and our deeds into one good and meaningful life.

Poetry has been a part of the worship of God as long as we know. It is not only the songs of Moses, Miriam, Deborah and David that show this. The very act of speaking about — and to — God requires us to use language in a way that goes beyond the prosaic, and uses the power of the music of words and ideas to connect us to the Divine.

There is good reason that our Torah and Haftorah portions are not simply read in speaking tones. Their moving power, present in the words and ideas, are powerfully augmented by the cadences and tonalities of the cantillation.

Through the ages, poetry has continually asserted its power. In the English language, the genius of John Milton was forthrightly and didactically religious.

As the modern world took shape, even though the openness to the didactic faded, the attraction of the spiritual did not. Giants of modernity, such as Yeats, Pound and Eliot, found the themes of religion inescapable, even if, in seeking authenticity, some were to stumble into the dark realm of antisemitism.

For all its precedent, there is something unexpectedly fresh and quick in the poetry of Yehoshua November. His is a distinctly informal and conversational mode of writing. His appeal is not to the authority of doctrine, whether religious or esthetic. His voice is that of a close friend inspired by the sudden intimacy of the conversation to hide nothing, lest the right moment never come again and his hard-won visions remain unshared. He respects the intimacy; even in confessional mode, he does not say more than you are willing to attend to.

And many of these poems are confessional, in that most important sense that they acknowledge a larger reality. This is no abstract acknowledgement of some hypothesis, but of a living reality already implicit in our own authentic emotions and thoughts. This larger reality, by its very existence, demands he — and we, too — account for ourselves in order to know how to transcend our own habitual limitations.

And so November takes us into his own life — remembrance of cruelty he inflicted as a child; a wondering that he has never imagined well enough how his wife has seen their marriage while he spent so much time setting down his own experience; his own realization of the inadequacies of his beliefs. Here, he speaks of his inability to reach a student in a remedial English class he taught at the state university:

I hate my life. I’m gonna fail this class

a second time.

He grabbed his phone and red sports drink.

slammed the door.

Then deeper silence:

quiet as water, field and sky

the millisecond

that followed man’s first failure.

(In the Middle of the In-Class Essay Exam)

Mishandled, such poetry could be tawdry and repulsive, like the insincere recitation of faults by a drunk to a chance partygoer that neither will wish to remember the next day. November does not mishandle. In the simplicity of his language, he evokes the way you would wish to talk to a dearest friend in life, evoking the desire to grow in wisdom and insight that makes us most human. In his poetry, his religious commitment as a Chasidic Jew is clearly lived as central to his art and fully integrated within it. He does not propose it as the answer to end all questions, but as the key to asking questions that mean most for him and his readers to ponder and live together:

When I was younger,

I believed the mystical teachings

could erase sorrow. The mystical teachings

do not erase sorrow.

They say: Here is your life.

What will you do with it?

(Two Worlds Exist)

This is genuine humility, having something to say precisely for knowing the limits imposed by truth and art. In his mind, this is bound up with the mystery of life lived within the pains and the limits of our bodies and the world itself and precisely there being called to the infinite. In The Possibilities of Language, he speaks of celebrity intellectuals proclaiming the incompatibility of having children and of real art:

A child is infinity

my rabbi said when we met

in the worn-down yeshiva coat room

after my wife had given birth.

A child is infinity he repeated,

without explaining.

Poetry is ideally suited to say things which cannot be explained, yet upon which all of life’s meaning may depend. November’s poetry, like the Chasidic texts he studies, are a mode of meditation — an integrative meditation that does not end when the book’s cover is closed, but accompanies one back into a life newly familiar, newly wondrous:

Sometimes, out of nowhere, the soul

awakens in the middle of the life in the body. And the world

cannot go back to its games in the same way.

(The Lower Realm)

Familiarity without cliché, intimacy without imposition, art, religion and life bound together in a lasting, passionate embrace — this one is worth your read.

To read the complete January 2017 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.