Technology keeps real-time conversations with survivors alive

Cincinnati’s Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center one of few museums in world to present Dimensions in Testimony exhibit

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

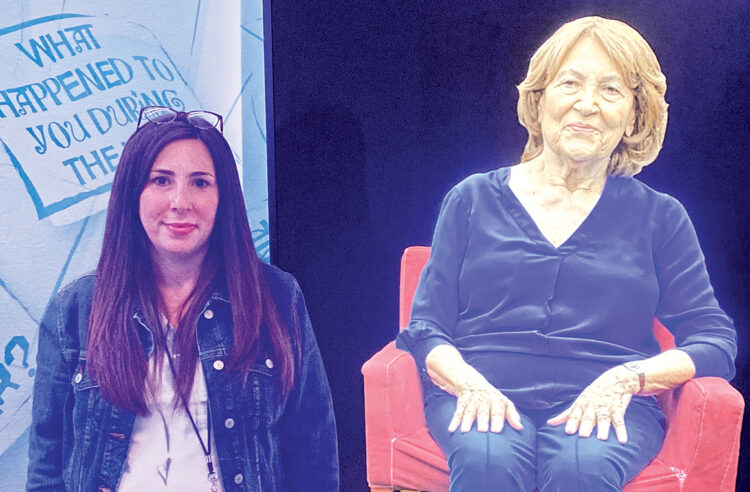

In a dimly-lit gallery designed for about 10 people, the focus is on a virtual life-size moving and talking image of Holocaust survivor Fritzie Fritzshall displayed on a door-sized video screen. Against a black background, Fritzie appears to patiently await questions, as she must have in front of so many school groups when she was alive.

On a wall next to her is a panel with her biography: born in Czechoslovakia in 1929, Fritzie was a slave laborer for nearly a year in Auschwitz II-Birkenau. She escaped the Nazis during a death march and eventually settled in Chicago, where she would serve as president of the Illinois Holocaust Museum and Education Center in Skokie.

On both walls next to her are questions visitors might consider asking to start up the conversation. A few feet in front of Fritzie is a microphone to ask questions.

Fritzie represents the newest technological effort to keep Holocaust survivors’ testimonies alive for the generations that won’t ever meet survivors in person. And The Nancy & David Wolf Holocaust & Humanity Center’s museum at Union Terminal in Cincinnati is one of only 10 museums in the world to exhibit these virtual conversations, Dimensions in Testimony, an initiative of the USC Shoah Foundation.

The world-class museum, which opened at Union Terminal in August 2019, is at the site of the train station where so many of Cincinnati’s Holocaust survivors arrived to rebuild their lives.

Sarah L. Weiss, the Holocaust & Humanity Center’s CEO since 2007, knew she wanted to incorporate Dimensions in Testimony into the museum’s new space.

“We decided, though, not to do it as part of the opening, because everything was so new,” she said. The plan was to open the Dimensions in Testimony gallery in the summer of 2020. Because of the Covid pandemic, she postponed the opening until February 2021. For that virtual opening, the real Fritzie offered greetings from her home in Chicago. She died in June 2021 at the age of 91.

“We are fortunate that we still have survivors that go into schools and speak — virtually at this moment (due to Covid) — but we know there will be a day when we won’t have that,” Weiss said.

Dimensions in Testimony is a way to continue that personal interaction with survivors, albeit through artificial intelligence.

The USC Shoah Foundation, which has recorded more than 55,000 video testimonies, has completed about 20 of these AI recordings of survivors for its Dimensions in Testimony project. Weiss said each of the 20 was recorded in California over one-week periods using dozens of cameras. Each survivor answered more than 1,000 questions about their Holocaust experiences and lives.

She estimated the cost to produce each Dimensions in Testimony survivor presentation at approximately $200,000. Of the 20, Weiss and her team have selected five for the Cincinnati exhibit in rotation. Fritzie recorded hers in 2015; it’s the only one Weiss has shown to the public so far.

“Our plan is to, every so many months, change the survivor story featured in this gallery,” Weiss said. “Fritzie will be up for several more months.” In January, the museum will present survivor Eva Schloss, Anne Frank’s stepsister.

“Her mother married Otto Frank after the war. And she and Anne grew up together. She is hoping to come in for that opening when we introduce her testimony.”

Weiss said two obstacles stand in the way of localizing the exhibit with survivors from the Cincinnati area: the expense, and that the complex technology still requires participants to travel to California to be recorded, a challenge for the frail elderly.

“There is a survivor in Florida right now who has been interviewed by the Shoah Foundation through this process, and he and his wife actually lived for most of their life after the war in Cincinnati,” she added. “We may eventually integrate his testimony.”

Over the 20 minutes I took to ask Fritzie questions, she appeared to take them in and consider them. She responded in a conversational way.

I asked her questions I’ve heard students ask Holocaust survivors, and questions I’ve put to survivors in interviews over the years:

• How did you come to America?

• Do you hold all Germans responsible for the Holocaust?

• Do you feel guilt because you survived the Holocaust?

• What were your favorite foods growing up?

• How did you survive the death march from Auschwitz?

• How did you get out of Europe?

• Do you think there could ever be another Holocaust?

These, she answered patiently and in detail.

To be sure, it seemed awkward at first to pose questions to the digitized version of late Holocaust survivor. Weiss said that’s not so for children.

“Kids are so used to talking to their computer and interacting with things,” she told me. She said that in the USC Shoah Foundation’s initial research for Dimensions in Testimony, it had a group of children interact with a survivor, and another group interact with the virtual version of the same survivor. Children asked more questions of the virtual version than the real person.

“Their hypothesis, from talking to the kids is that the kids thought there was less of a barrier,” she said. “They felt more comfortable asking certain questions that they might not feel comfortable asking: they might think they wouldn’t ask it right. It took away their vulnerability. For especially a 12-year-old, 15-year-old, asking a survivor a question, it can be intimidating.”

One question Fritzie couldn’t quite answer: I asked if she was raised in a traditional Jewish household. Her reply didn’t correspond to the question. I tried another way. “Were you raised in an Orthodox household?” This time, a different response, still not related to the question.

Then I asked Fritzie “Do you believe in God?”

Her reply: “I was raised in an Orthodox home, Jewish, Orthodox home. I remember my grandfather laying tefillin every morning while I visited him. And the Jewish tradition is the belief in God. And I went into concentration camp like everyone else that was raised in a Jewish home. Did I know much about God at that point? No. I was a child, I don’t know that much about the Torah, I didn’t have a Jewish education. But the subject of God has come up a lot with students. I believe that if there was a God in Auschwitz, God did not speak up. God sat on a fence looking at his people and wasn’t there to help his people. And so, I have my issues with that question.”

When I asked Fritzie why she agreed to be recorded for this project, she said, “Every time I stand up and I tell my story, it opens the wound. It brings back the past, and I see it. Why do I do it? I ask myself often, why do I do this to myself, why do I do it? I feel that I have an obligation as a survivor to tell the world what happened. I have an obligation to teach. I have an obligation to remember that it’s important to me to leave my story behind so that the next generation can learn from me what I have gone through. And maybe, it might touch one child. I need for the world to know. And this is why I do it.”

To read the complete October 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.