A fair shake by Dayton’s dailies

How Dayton’s daily newspapers covered local Jewish life — long before local Jewish newspapers did

By Marshall Weiss

Reprinted with permission from Ohio Genealogy News, Summer 2020

On the afternoon of Wednesday, Oct. 7, 1863, Dayton’s 40-plus Jewish families held a grand celebration: the dedication of the first synagogue building in this city of approximately 20,000 people. Holy Congregation B’nai Yeshurun, now known as Temple Israel, had purchased the building at the northeast corner of Fourth and Jefferson Streets from a Baptist church.

Two local daily newspapers, the Dayton Journal (Republican) and The Daily Empire (Democratic) presented vivid accounts of the proceedings in their issues the next day.

Because of the Journal, we know the procession to the new synagogue included “a large number of pretty little girls, dressed in white, beautifully decorated, and they were marching in couples, then young ladies charmingly costumed, and exquisitely decked with head dresses and scarfs, succeeded them.”

We also know from the Journal that “prominent members” of the congregation followed them, carrying three Torah scrolls, “covered with the richest velvet cloth, with crowns in decoration, followed under a canopy.”

“The Jews may well be proud of their beautiful place of worship,” The Daily Empire pronounced to its readers.

Over the next few days, each newspaper ran corrections about the event. Both had listed the name of the congregation’s new rabbi, “Rev. Mr. Delbanco,” incorrectly. It’s possible the congregation printed his name wrong in the event program, and the papers likely followed suit.

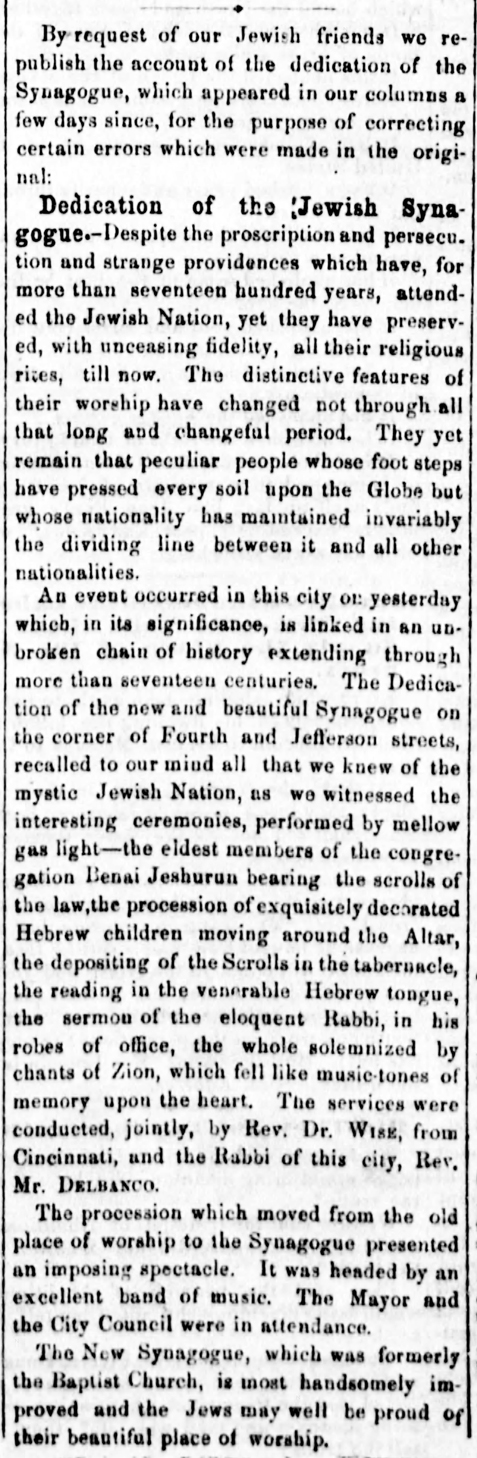

Not only did The Daily Empire run this correction, it reprinted the entire article with two items not mentioned in the first version: a notation that “the eldest members of the congregation” carried the Torah scrolls in the procession to the new synagogue building, and that the mayor and city council were in attendance. This revised version of the article begins with a clear explanation: “By request of our Jewish friends we republish the account of the dedication of the Synagogue…for the purpose of correcting errors which were made in the original.”

More than 150 years later, I am glad The Daily Empire did so, not only to clarify the record but to add even more detail to help later generations better visualize the scene.

It’s also one of numerous examples in Dayton’s daily newspapers — and across party lines — of their interest in and detailed coverage of this small Jewish community from its near-beginnings through the 20th century.

This was long before a Jewish press raised its own voice in Dayton, though Jews here could look for some coverage of our community in Cincinnati’s American Israelite (established 1854) and the Ohio Jewish Chronicle, based in Columbus (established 1922).

The first known Jewish newspaper in Dayton, The Dayton Jewish Life, published for about a year: from the end of 1917 to the end of 1918. Temple Israel attempted to publish The Dayton Jewish Record between 1934 and 1935. It wasn’t until 1959 when Dayton had its own Jewish newspaper again — the Dayton Jewish Chronicle — this time until 1995. Since 1996, I’ve had the honor of serving as editor of the Gem City’s current Jewish newspaper.

When I began my research into Dayton’s Jewish history, I was pleasantly surprised to find the local dailies were such treasured resources. I read for myself that the earliest Jews to arrive in Dayton became active participants in the betterment of the general community, and that they were given a seat at the table. And in situations where they weren’t, the daily papers here would call it out.

With the advent of Newspapers.com, quick access to these publications helps me find information in minutes that might otherwise take weeks.

Early Jewish life in Dayton

The first Jews to settle in Dayton came in the 1840s. They emigrated from Prussia and Bavaria, where they were prohibited from certain professions, places they could live, and often from legally marrying. They generally met with success in Dayton, working their way up from peddlers to shop owners.

When the first key leader of Dayton’s Jewish community, Joseph Lebensburger, died at age 65 in 1877, the Dayton Journal reported: “He was largely known in the vicinity and highly esteemed.” We also learn from the Journal that he was a Mason, an Odd Fellow, a member of the Ancient Order of United Workmen, and the Red Men.

As far back as 1860, The Daily Empire sporadically included information about upcoming Jewish holidays, their significance, and how they were observed. In 1865, the publication included an account of a local Jewish wedding.

“We had the pleasure of witnessing on yesterday afternoon, the lengthy and peculiarly impressive ceremonies of a Jewish marriage at the house of Mr. L. Jacobs,” the Empire reported Aug. 15, 1865. “May success attend the new married pair in the realization of their fondest hopes in the married life.”

The Journal also offered information about Jewish holidays and included goings-on of members of the Jewish community on its society page.

“A HAPPY NEW YEAR!” That is the Manner in which Jew Greets Jew To-Day, read a Daily Herald headline, Sept. 14, 1882.

That year, the Daily Herald also included in its society column an item about an employee with Dayton’s German Jewish social club: “Mr. Joseph Beatus, who so acceptably filled the position of janitor for the Standard Jewish Club, during the past nine years, has resigned the position greatly to the regret of many members of the Club. Joe has gone back to his old business as an optician.”

An affinity for social reform

When James Cox started the Dayton Daily News in 1898, his Democratic newspaper also published information about Jewish holidays and included Jews in its society column. Two years later, with the arrival of Rabbi David Lefkowitz to serve B’nai Yeshurun synagogue, Cox was present at the young Lefkowitz’s first sermon in Dayton. In short order, Lefkowitz became known for his sermons on social reform.

Cox — a progressive Democrat who would later serve three terms in the U.S. House of Representatives and three terms as Ohio’s governor — saw to it that the Dayton Daily News began to cover Lefkowitz’s lectures. He first showed up in the March 31, 1900 issue of the Dayton Daily News when Cox published the “touching” eulogy Lefkowitz delivered the night before at the synagogue in memory of Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise, the Cincinnati-based architect of Reform Judaism in America who was also Lefkowitz’s teacher.

A month later, Lefkowitz appeared in an extensive society item in Cox’s paper. The rabbi had officiated at the wedding of Corrine Pollack, daughter of Dayton’s successful whiskey wholesaler and celebrated Civil War veteran, Isaac Pollack, to a young man from Lexington, Ky.

As common in society items of the day, the report described the gowns worn by the women of the wedding party and shared the dinner menu, which shows us how Dayton’s Reform Jews dined (decidedly not kosher, but still no pork) in those days.

“The banquet hall was beautifully decorated with lilies, palms, white roses and carnations, and the glow of rose-shaded candelabra gave a bewitching radiance to the festive scene,” we learn of the reception and ball at the Standard Club. “The color scheme of white and green prevailed throughout the house and the appointments were elegant.”

The Dayton Daily News started listing Lefkowitz’s upcoming synagogue sermons. Non-Jews began attending Friday night Sabbath services at B’nai Yeshurun to hear what he had to say. And Lefkowitz would receive invitations to deliver lectures to civic groups and for high profile public occasions, which Cox would also cover.

Lefkowitz, described in the Dayton Daily as “the thrilling and eloquent leader of the modern Jewish church in this city,” delivered the oration at the annual memorial service of Encampment No. 83 Union Veteran Legion in 1902, a speech to the student body of Steele High School and a “stereopticon talk” at Christ Church about the Great Men of Israel in 1903, and the eulogy for the annual memorial services of Gem City Council, No. 3, United Commercial Travelers in 1904.

The Journal and Herald began listing the rabbi’s upcoming sermon topics during that decade too. They, along with the Dayton Daily also reported on happenings in Dayton’s more recently established synagogues of impoverished Orthodox Jewish immigrants flooding into America from Eastern Europe: House of Jacob and House of Abraham in Dayton’s East End, and the multitude of Jewish clubs and service organizations that sprang up here at the turn of the 20th century.

Jewish news without a Jewish newspaper

A comfort level became apparent among the local dailies and the somewhat Balkanized segments of Dayton’s Jewish community that allowed for open, honest coverage of the Jewish community — and in the absence of a sustainable local Jewish newspaper.

For Jews who could read English, the daily papers enabled them to learn about aspects of Jewish life and sensibilities from other parts of the Jewish community which they may not have encountered in their daily lives at that point.

In some ways, this may have nudged segments of the Jewish community closer together in the lead up to the great unifiers soon to come: the Great Dayton Flood of 1913 and World War I.

Zionism, which was not yet a settled issue across Judaism’s movements, was actively covered, discussed, and debated in the dailies, with local Jews weighing in.

At the request of the Dayton Daily, attorney Ishur L. Jacobson wrote the article, Will the Jew Return to Palestine? How the World War Will Effect Zionist Movement, Sept. 5, 1915.

Rabbi M. Lichtenstein of the Wayne Avenue Synagogue (Beth Abraham) took Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg of the Jefferson Street Temple (B’nai Yeshurun) to task in the March 20, 1921 Dayton Daily News, castigating Mayerberg in detail for his statement that the Jews are not a nation, but “a race with a religious ideal.”

Not only did the local Dayton papers widely cover the antisemitic pogroms of Eastern Europe before, during, and after World War I, this coverage rallied leaders in Dayton’s general community. They gathered publicly with Dayton’s Jews, condemned the violent hatred, and helped raise funds for its victims. This was documented in detail in those papers, which also published unsigned editorials in support of the “Russian Jews” who had immigrated to the United States.

On at least one occasion, a political fight within a synagogue spilled over to a daily, with both parties knowingly airing their beefs in the public eye. Expect Big Doings At Annual Election Of House Of Jacob announced a Dayton Herald headline Aug. 2, 1910 of a “hot contest” for synagogue president between supporters of longtime president Nathan Bader and Harry Office.

“Friends of Office have their ‘knives out’ for Bader’s scalp and it was said Tuesday that even if Bader does get enough votes to be elected, steps will be taken to prevent him from serving,” the Herald exclaimed.

After the election, the Herald reported Aug. 8 that by a margin of one vote, “irregularities were alleged in the annual election” and that “court proceedings were threatened to prevent Nathan Bader from again taking his seat as president of the congregation.”

But on Aug. 15, the Herald reported the conflict was resolved “in the interest of harmony.” Bader withdrew from the presidency although he claimed he was “regularly and legally elected president.”

A fair shake during a dark era

The 1920s and ‘30s marked the shift to the most antisemitic period in America — until the Jew hatred and mass killings of Pittsburgh, Poway, Jersey City, and Monsey in our time. And a century ago, Dayton’s dailies stood firm to give the region’s Jews a fair shake.

When Dayton became a hotbed of Ku Klux Klan activity in the early 1920s, the dailies covered it thoroughly. The Dayton Daily News trumpeted that it had brought to the attention of the Montgomery County Commission that the county had allowed the Klan to book a meeting for May 26, 1922, to be held at the county’s war memorial auditorium, Memorial Hall.

When the county commission failed to take action to stop the Klan meeting, the Dayton Daily reported this, and that B’nai Yeshurun’s Rabbi Samuel Mayerberg, civic and business leader M.J. Gibbons Jr. (Catholic), and the Rev. John N. Samuels-Belboder, pastor of the African American St. Margaret’s Episcopal Church, had filed an injunction to bar the Klan from rallying not only at Memorial Hall, but anywhere in the county.

The attorneys who prepared the injunction were active in civic affairs as well as with their respective religious communities: Sidney Kusworm, a Jew; and John C. Shea, a Catholic.

A county judge granted the injunction hours before the scheduled event. All of this made the front pages of the local dailies. (U.S. Supreme Court decisions that would set the bar high for freedom of speech were not yet in place.)

Later that year, on its Dec. 9, 1922 front page, the Dayton Daily reported on Mayerberg’s fiery sermon of the night before at B’nai Yeshurun in which he challenged Dayton’s Council of Churches to issue a statement condemning the Klan.

“The Protestant church has a great opportunity to teach a lesson in vigorous Americanism by condemning this vile un-American organization,” Mayerberg declared.

The next day, the Dayton Daily reported the council’s tepid reply: “The Dayton Council of Churches went on record about a month ago as denying certain rumored connections with the Ku Klux Klan…little more than a month ago the Federal Council of the Churches of Christ in America issued a statement to the press. It was endorsed by the Dayton Council of Churches officially disclaiming any control over or interest in the Ku Klux movement.”

Two physicians, two stories

The stories of physicians Dr. Leo Schram and — a generation later — Dr. Hans Liebermann, show how antisemitism grew in Dayton over that period and how the local papers responded. Both of their lives were well covered over several decades in Dayton’s dailies.

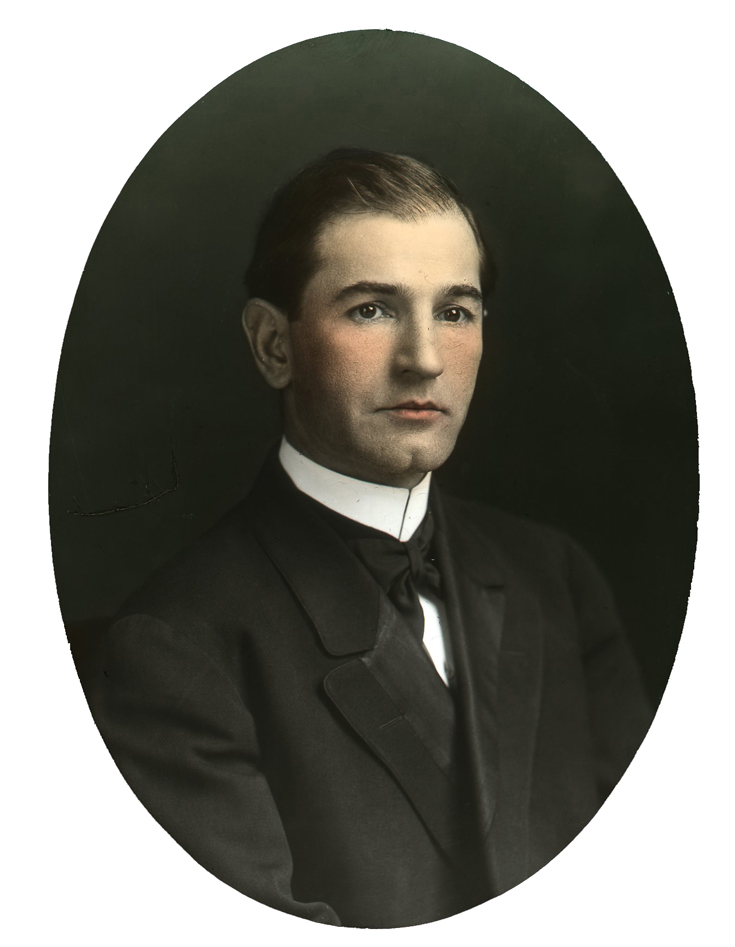

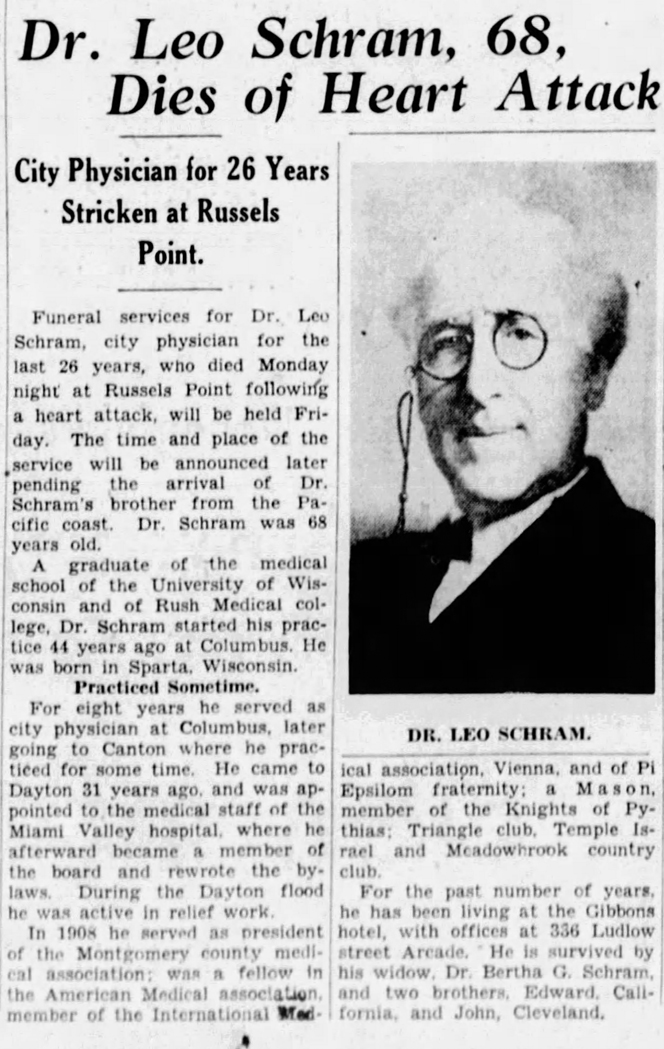

Wisconsin native Dr. Leo Schram, a Jew, was elected president of the Montgomery County Medical Association (now Society) in 1908. He served as Dayton’s city physician for more than two decades, conducting physicals for students in Dayton’s public and parochial schools. Schram was chief medical consultant and on the executive board of Miami Valley Hospital. He was also a member of the Triangle Club, Knights of Pythias, and a Mason.

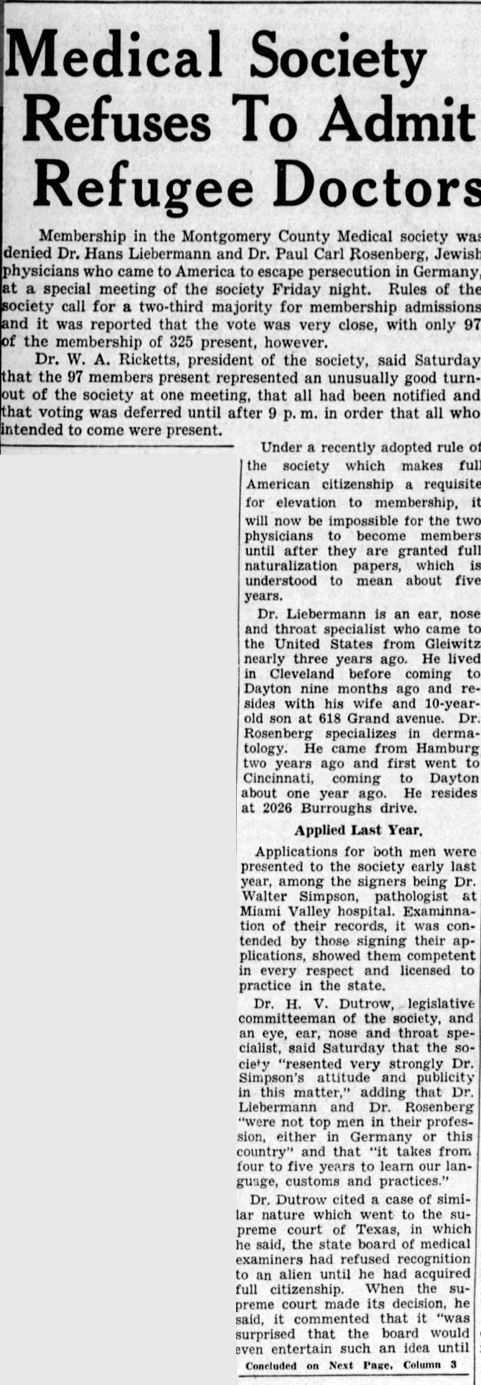

In 1938, physician Dr. Hans Liebermann, also a Jew, fled Nazi Germany, passed the Ohio State Board Medical Examination, and then arrived in Dayton in 1939. Office buildings refused to rent Liebermann space for his practice, even though occupancy was low at the time. Three hospitals at first rejected his application for privileges, even though he had his own ear, nose, and throat practice in Germany since 1928.

He, along with another Jewish refugee doctor, was rejected for membership in the Montgomery County Medical Association in January 1940 — the very society of which Schram was president 32 years before.

Liebermann would later recount in an oral history that as soon as the local papers reported on the medical society rejections, new patients showed up at his office to support him. He would go on to assist several hundred Jewish families resettle in Dayton after World War II and supplied affidavits for Jewish families to enter the United States.

As of three years ago, when I was finishing my book, Jewish Community of Dayton, the Montgomery County Medical Society had no information that Dr. Leo Schram had ever served as its president, even though this had been well-documented in Dayton’s dailies. Now that I think of it, it’s time to provide the society with this easy-to-confirm information, so the good doctor of a century ago can receive the recognition he deserves.

Marshall Weiss is editor and publisher of The Dayton Jewish Observer, project director of Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, and author of Jewish Community of Dayton (Arcadia).