How we navigated the Spanish flu of 1918-19 in Dayton

‘So many hearts are overwhelmed with sorrow’

One more palpable cause of worry and grief piled on top of the Great War.

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Although The Dayton Daily News reported on Oct. 5, 1918 that Dayton Health Commissioner Dr. A.O. Peters thought there was undue alarm about the Spanish influenza outbreak that had hit about 20 people locally, by Oct. 8, Dayton had 168 reported cases.

The same day, the Ohio Department of Health laid out closure recommendations, and Peters closed schools, houses of worship, and theaters. The next day, he closed saloons, soda fountains, and pool rooms.

According to the University of Michigan Influenza Encyclopedia, Peters thought the crest of the epidemic had passed, “that Dayton’s death rate slowly would return to normal in the coming weeks.” As a precaution, though, he would keep closures in place for another week to 10 days. But as adult cases decreased, children’s cases increased.

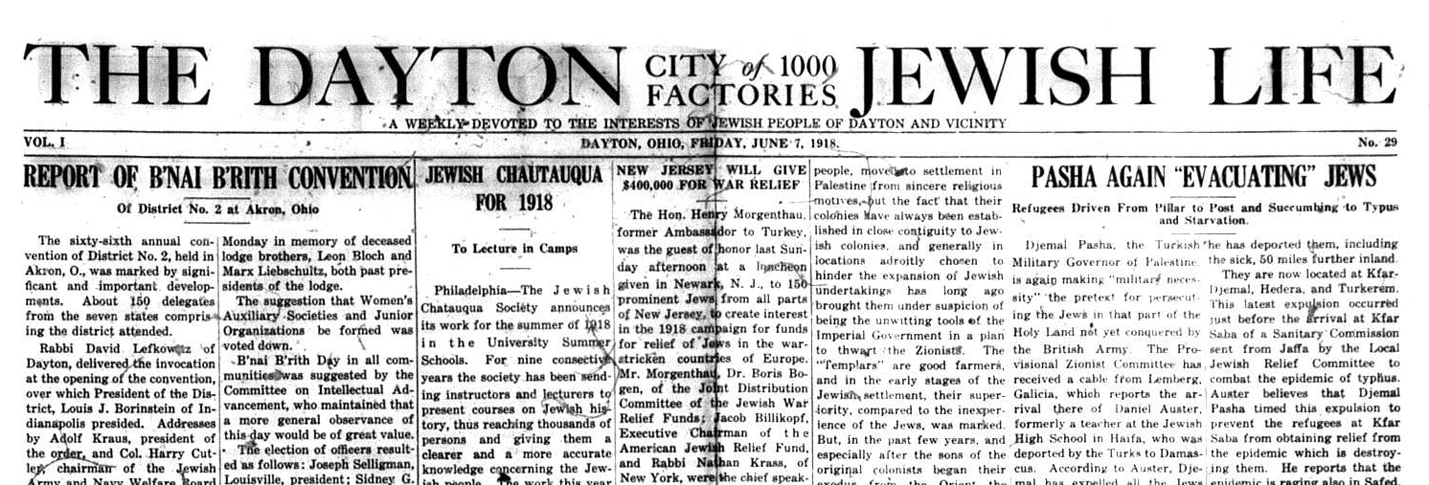

What we know about how the Jewish community was affected by the pandemic here in 1918-19 comes to us mainly from the pages of The Dayton Jewish Life. Billed as “The First and Only Jewish Paper in Dayton,” its editor and publisher was Andrew Roth. The newspaper’s run was brief: from the end of 1917 to the end of 1918.

Roth may have started The Dayton Jewish Life to leverage news stories coming out of the new Jewish Correspondence Bureau, which was reporting on conditions facing Jews in war-torn Europe. Its editor was Jacob Landau, a 25-year-old journalist in The Hague. The Jewish Correspondence Bureau was soon renamed Jewish Telegraphic Agency.

The Dayton Jewish Life covered local news of the Spanish flu in an understated way: not with headline stories on the front page but in society items, news briefs, event listings, and a few unsigned editorials.

The first Spanish flu item in The Dayton Jewish Life appeared in its Oct. 11, 1918 issue: “Dr. A.M. Osness, with offices in the U.B. Building, has been called East to help combat the Spanish influenza epidemic, which seems to have the hardest hold on Boston. On Thursday evening, Dr. Osness left for Boston to be gone until the spread of the Spanish influenza is under control.”

Born in Berdichev, Ukraine in the Russian Empire in 1864, Abraham M. Osness arrived in America in 1882 and settled in Dayton to learn the cigar making trade, according to Centennial Portrait and Biographical Record of The City of Dayton and of Montgomery County, Ohio edited by Frank Conover and published in 1897.

Osness attended high school and a commercial college here. He received his medical degree in 1894 from the College of Physicians and Surgeons in Chicago and returned to Dayton to open his practice. His wife, Anna K. Osness, would found Dayton’s chapter of Hadassah in 1925.

The Dayton Daily News reported Osness had volunteered as a consulting physician and was assigned to duty at Pittsfield, Mass. by the government. When Osness returned to Dayton three weeks later, Dayton Jewish Life reported, “The time spent there in his effort to get the influenza epidemic under control has proven quite fruitful.”

Comforting the boys quarantined in the camps

The spread of the Spanish flu pandemic in America was connected to the movement of soldiers across America and Europe after the United States entered the Great War in 1917.

Members of Dayton’s chapter of the Jewish Welfare Board — established here in July 1918 to provide support for Jewish and non-Jewish soldiers stationed locally — did their part to help soldiers confined to their quarters under quarantine.

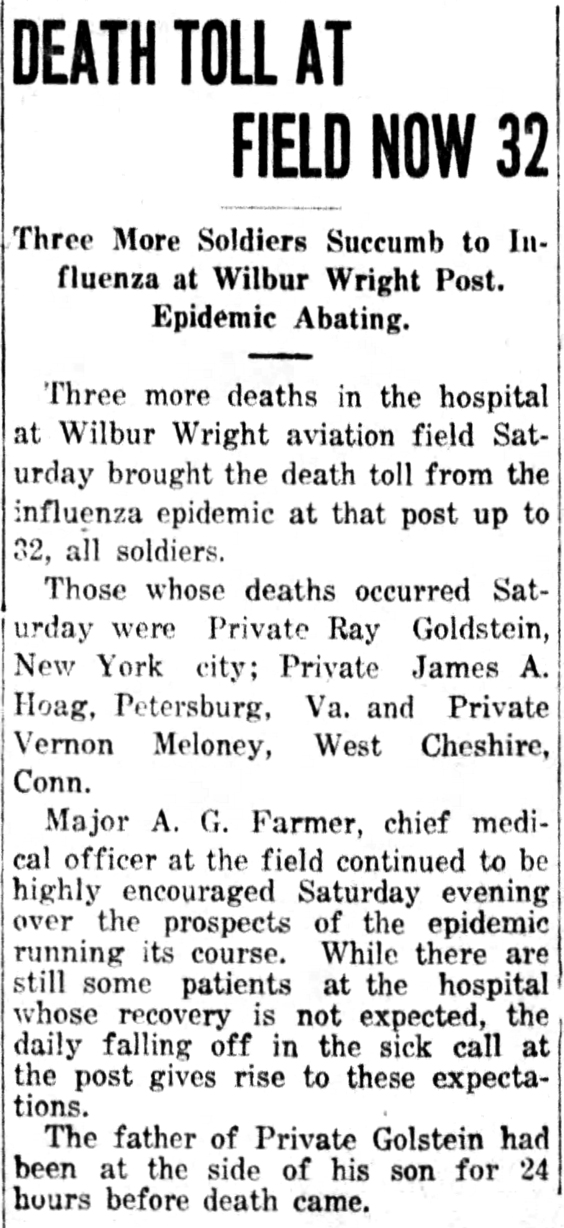

“During the time that the Spanish influenza epidemic was at its height at the Wilbur Wright and McCook Fields, the local branch of the Jewish Welfare Board did all in its power to aid in the fight against the epidemic and to save the lives of the boys there,” Dayton Jewish Life reported on Nov. 1, 1918. “Large quantities of ice cream, crates of oranges and lemons were sent to the field.”

The paper also reported in that issue that two of the fatalities at Wright and McCook Fields were Jewish.

“It is with grief and regrets to all and especially to those who knew them, that Benjamin Goldstein and Ray Goldstein, both of New York and not related, passed into the great beyond.”

Dayton Jewish Life added that Benjamin Goldstein’s struggle was “hard but brief,” and Ray Goldstein “fought a hard but losing battle for almost a week,” and that “his fight attracted the attention of the attendants and his comrades, for no other fought so hard and lost.”

The Oct. 12, 1918 Dayton Daily News reported that Ray Goldstein’s father was at his side for 24 hours before he died.

A Jewish soldier buried in Dayton who was likely a casualty of the Spanish flu was Army Private Ervin M. Welt. Born in Cromwell, Ind., Welt was a jeweler from Schenectady, N.Y. He was the husband of 23-year-old Leah Jo Moskowitz, daughter of Dayton’s Sallie and Jacob Moskowitz. Leah’s father had made his wealth establishing Hungarian labor colonies in Dayton for Malleable Iron Works and Barney and Smith Car Works.

The Dayton Daily News reported in its Jan. 16, 1918 society column that Leah and Ervin had married the night before in the Moskowitz family home on Lexington Avenue.

“The bride’s gown was of silver cloth with draperies of silk tulle,” the Daily News noted. “It was made short and the tulle veil fell just to the hem. The bodice was of pearl passementerie, and she carried Ascension lilies. Her costume was suited to her brunette beauty and she looked very sweet and girlish as she took her place to plight her vows.”

Ervin enlisted in the army July 24, 1918. He died of pneumonia — often a complication of the Spanish flu — Oct. 8, 1918 at Camp Sherman, near Chillicothe. The 26-year-old private was buried at Temple Israel’s Riverview Cemetery next to Sallie and Jacob’s infant son, Joseph, who died in 1900.

On Ervin’s gravestone is the Hebrew word mizpah, literally, watchtower. In Judaism, mizpah signifies the emotional bond between people who are separated.

About 17 years later, Leah, then living in New York, married actor Harry C. Bannister, the ex-husband of stage and screen star Ann Harding.

According to the National Park Service, approximately 5,686 cases of influenza were documented among Camp Sherman soldiers in 1918. Of those, 1,777 of them died. NPS notes that “43,000 U.S. soldiers, around half of those who died in Europe during the war, were killed by the influenza virus and not by a mortal enemy in combat.”

Another Jewish casualty with Dayton connections was Capt. Arthur Pereles, 30, who died at his home in Montclair, N.J. on Oct. 8, 1918. Born and raised in Dayton, he was the son of Marguerite and Morris Pereles, who owned the London Hat House. Arthur had done well in the importing business. He enlisted in the army after the war broke out and became ill with the flu on Sept. 30, 1918. Arthur was buried in Montclair, leaving his wife and two children.

Welt and Pereles are the only known soldiers connected to Dayton’s Jewish community to die as part of the Great War. There are 189 known World War I casualties from Dayton, 85 of which died from disease, mostly the Spanish flu.

According to the CDC, by the time the Spanish flu had abated, it killed 50 million people worldwide, with about 675,000 deaths in the United States.

The Spanish flu had become one more cause of worry and grief piled on top of the Great War.

B’nai Yeshurun’s Rabbi David Lefkowitz, who also chaired Dayton’s Red Cross chapter, had put the Great War front and center in his Jewish New Year message in the Sept. 7 Dayton Jewish Life, in those few weeks before the Spanish flu’s arrival here:

“In all my 18 years of ministration in this community, none has been as difficult, as full of work as this last year…never was the community more severely tried than during this selfsame period. And I have not forgotten the flood, when I say this, with all its lurid horror and heavy losses. For month after month in the last year, our fine young men have been called from their homes and loved ones, mothers with palpitating hearts bade tearful farewells, and fathers, dry-eyed yet heartstricken, sent their sons to their country’s service.

“The entire community heart was constantly palpitating and fearing and yearning…Along with the rest of the citizens of Dayton, our Jewish people stood the test of patriotism. They gave without stint. They gave their sons. At the present time, 88 Jewish men of Dayton are in the service, many of them enlisted. Forty-one of these are overseas, some in England, but most of them in France. Thirty-eight of the 88 are from Congregation B’nai Yeshurun and the others from Congregation House of Abraham and from Congregation House of Jacob. More men are being called every few weeks and before October we shall have over 100 Jewish men from Dayton in the service.”

Jewish Life society pages & news items

Since it began publishing, Dayton Jewish Life included announcements on its society page of who was ill and who was recovering from illnesses, though it rarely mentioned what those illnesses were. But with the spread of the Spanish flu epidemic in Ohio in autumn 1918, a smattering of announcements began listing the Spanish flu and pneumonia as causes.

The Nov. 1, 1918 Dayton Jewish Life, for example, announced that “Corporal Harry Feinberg stationed at Ohio State University is recovering from a severe attack of influenza and pneumonia.”

The same issue listed Herbert D. White, manager of Dayton Jewish Life, “confined to his home on Lawn Street, suffering from a slight attack of the Spanish influenza.” The Dec. 6, 1918 issue informed readers that “The many friends of Mrs. Lester Kusworm will be grieved to learn that she is suffering from the popular malady, la grippe.” La Grippe was another term used to describe the Spanish flu.

In consultation with the Ohio Department of Health, Dayton Health Commissioner Peters lifted restrictions against public gatherings on Nov. 2, 1918, though schools were still kept closed because of the higher rate of flu among children. Youths under 16 were also prohibited from worship services, theatres, and libraries.

Leaders of Dayton’s Talmud Torah, the Hebrew school of Beth Abraham and Beth Jacob synagogues, lamented in the Nov. 1 Dayton Jewish Life that though its roster of students had doubled from the previous year, and Talmud Torah Superintendent S.B. Maximon had brought an additional Hebrew teacher — Deborah L. Abramson — from New York to Dayton, “the new term’s work, already in full swing, has been interrupted by the quarantine.”

Peters ultimately opened the schools, only to close grade schools again beginning Dec. 10, 1918 through the rest of the year because 20 percent of public school students and 10 percent of parochial school students were absent; approximately five percent of students had the flu and parents were afraid to send their children.

The worst of the epidemic — according to Peters and Dayton Director of Public Welfare Dr. Frank D. Garland in their 1919 report — hit the city between October and December 1918, when 657 residents of Dayton died from influenza or influenza-related pneumonia. Forty-four more people died here in January 1919.

Even so, with the ban on public gatherings lifted, Dayton’s B’nai B’rith lodge was able to announce in the Nov. 15 Dayton Jewish Life that its annual dance, a Chanukah ball which had been scheduled for Nov. 26, was a “sure thing.”

The Young Men’s De Hirsch Club, a Zionist organization, reported it held a meeting Nov. 10, its first since the epidemic closing orders.

“Many letters from De Hirshites who are in the service were read. This is a real treat to the members and at each meeting the recipient of letters brings them, and the entire attendance enjoy the contents which is always a message of good cheer.”

Temple Israel, then known as B’nai Yeshurun, announced that with the closing ban lifted, its children would begin attending classes again the following Sunday, and that “due to the closing order the plans for a Chanukah entertainment must be changed. As yet nothing definite has been decided upon but the children may expect a treat as usual.”

Yiddish theatre star Sara Adler performed in the play Mothers of the World in Dayton on Nov. 7 and “won her audience so completely,” she presented two more plays here over the next few days: Without A Home on Nov. 11 and Broken Hearts on Nov. 17. With the armistice in place on Nov. 11, several playgoers missed Without A Home to participate in Dayton’s peace celebration.

“Many people are prone to believe that the Madam Adler in their midst is not the real artist, feeling that Dayton’s Jewish community is not large enough to warrant her coming here,” Dayton Jewish Life reported. “However the Madam wishes to give the Dayton people a treat, realizing that such events as Jewish plays are rare delights here and for that reason she has allowed herself to be urged into coming back for a second and even third time.”

The Dayton Zionist District held a meeting at the Wayne Avenue Market Hall on Nov. 24 with 350 people in attendance to celebrate the American and Allied victory and the one-year anniversary of the Balfour Declaration, which declared Great Britain’s support for a Jewish homeland in Palestine.

Jewish civilian deaths

We know of three deaths as a direct result of the Spanish flu and another two likely from complications of the Spanish flu in Dayton’s Jewish civilian population at the time. Of the five, two are buried at Beth Jacob Cemetery, three at Beth Abraham Cemetery.

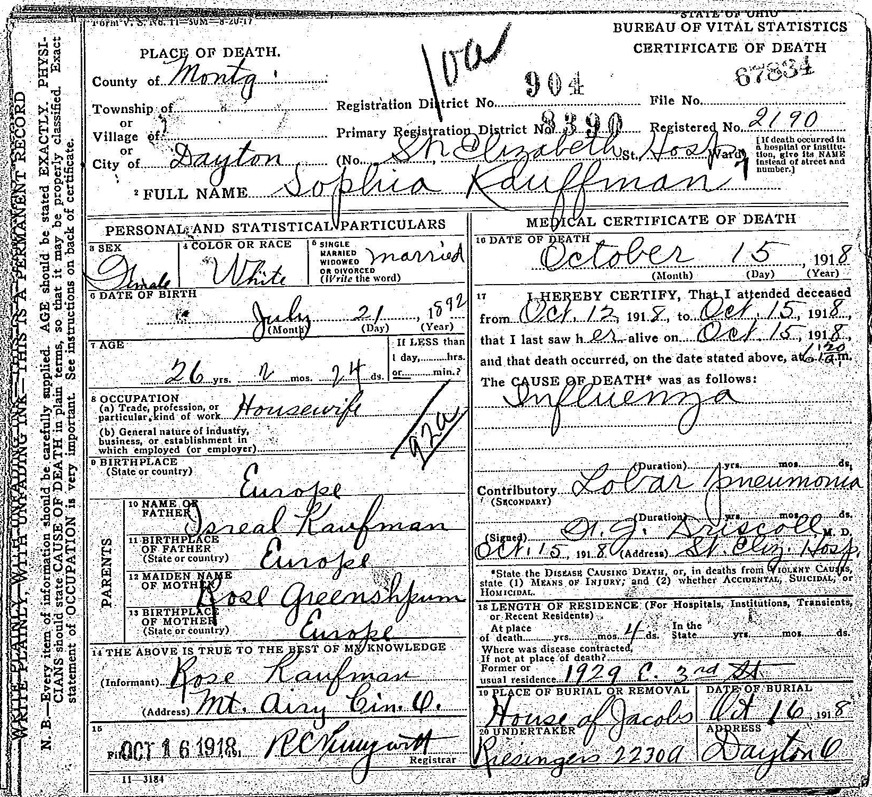

Sophia Kauffman was born July 21, 1892 to Israel and Rose Kaufman in the Russian Empire. She immigrated to the United States in 1907 and found work in Cincinnati as a men’s clothing finisher. Israel and Rose arrived in the United States in 1909 and in Cincinnati, Israel became the foreman of a piano factory.

She added another F to her name when she married 23-year-old tailor Nathan Kauffman of Dayton on Dec. 9, 1917 in Cincinnati.

Sophia’s husband, Nathan Kauffman, was born Feb. 28, 1895 in the Russian Empire. He arrived in the United States in 1912. On their marriage license, Sophia fudged her age to appear younger, claiming she was 23 though she was 25. The couple lived at 1929 E. Third St. in Dayton, and she took on the role of housewife.

Sophia died at St. Elizabeth Hospital on Oct. 15, 1918 at age 26. She is buried at Beth Jacob Cemetery. Her death certificate records the cause of death as influenza.

Morris Solomon, the son of woodworker Max Solomon of Romania and Leah Cohen Solomon of the Russian Empire, was born Sept. 2, 1902 in Manchester, England. Max was a cabinetmaker with the Dayton Wright Airplane Company in Moraine.

The Solomon family arrived in the United States in 1910 and lived at 1613 E. Fifth St., Dayton. A student, Morris died at home Oct. 31, 1918 at age 16. He is also buried at Beth Jacob Cemetery. The cause listed on his death certificate is bronchopneumonia, very likely a result of the Spanish flu.

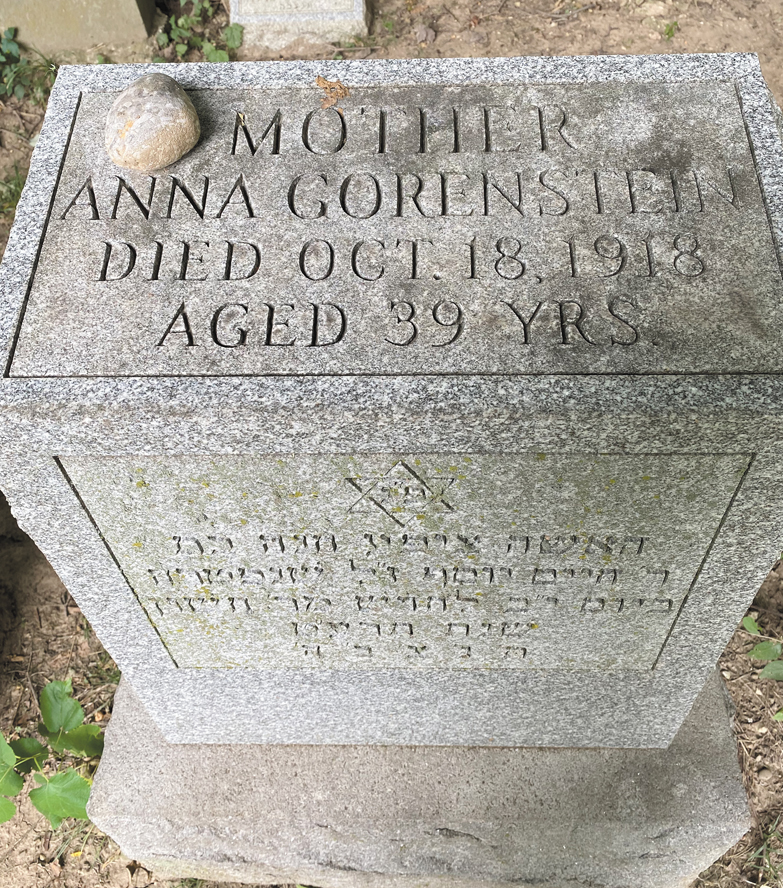

Buried at Beth Abraham Cemetery is Anna Gorenstein, a housewife, who died at Miami Valley Hospital of bronchopneumonia on Oct. 18, 1918 at age 39. She and her husband, Harry, a salesman, lived at 446 East 5th St. Both were born in the Russian Empire as were their two oldest children. Harry was left to raise their two sons and two daughters: an infant, a toddler, and two teenagers. A few years later, he would remarry.

Sam Silberman, who died of influenza at Miami Valley Hospital Dec. 17, 1918 at age 52, is also buried at Beth Abraham Cemetery. Little else is known about this Jew from Russian Poland whose name never appeared in Dayton’s city directory; on his death certificate, his occupation is listed as unknown, and his marital status is left empty.

Fruit peddler Nathan Berlin, born in the Russian Empire, died of influenza at Miami Valley Hospital Oct. 27, 1918 at age 27. He left behind his wife, Sarah, and their three children — Max, Benjamin, and Minnie — all under age 4, at 229 Allen St. Nathan Berlin is buried at Beth Abraham Cemetery.

“He was helping his uncle — that was Mr. Hyman Schriber — because he was sick, and my grandfather Nathan caught the flu and died,” Natalie Cohn of Dayton told The Observer. Natalie is Minnie’s daughter; she was named for her grandfather.

Natalie’s grandmother Sarah had arrived in the United States in 1914 from Latvia. After Nathan’s death, Sarah opened a grocery store with a relative, Samuel Kramer, at 712 S. Wayne Ave. Within a few years, Samuel went back out as a peddler and Sarah was on her own with the store.

“It was a deli, with a pickle barrel and all the deli stuff,” Natalie said. As children, Natalie’s uncles and mother helped their mother, Sarah, in the store.

Natalie said that for a very brief period, her grandmother Sarah remarried.

“He was a shochet (kosher slaughterer) who lived next door,” Natalie said. “He took a liking to my grandmother. My mother didn’t like that. Meanwhile, he got her to marry him. That didn’t last long.”

In the early 1930s, Sarah moved her grocery to the 1900 block of Home Avenue on the West Side. She died in 1944 at about age 50, when Natalie was 5.

“My grandmother was just so sweet and generous,” Natalie recalled. “She lived with us upstairs and she wasn’t well. My mother would make a tray of food for my grandmother and I would take it up to her.”

In 1947, Natalie’s parents, Minnie and George Rudin, would open the Tropics, a Polynesian-themed nightclub at 1721 N. Main St., which they ran for 40 years. Minnie’s brothers also worked there.

Spiritual reflections on the pandemic and the war

The Oct. 25, 1918 Dayton Jewish Life included two unsigned editorials with themes of life and death, well past the High Holy Days, which had fallen in the middle of September, before the epidemic hit Dayton.

“In order to compensate for the discontinuance of public worship, in a number of communities, leaders of respective houses of worship issued a call that the members of their congregations should hold a home service at the hour when the public services are usually conducted…We wonder to what extent this old and beautiful custom of Israel was carried out. We wonder whether those of our people who have practically banished religion from their home, grasped the opportunity offered at this time, to make their homes sanctuaries unto God. We wonder whether this terrible scourge will cause them to see the need of giving Judaism the chief place in their lives, in this time of storm and stress, of sickness and perchance death.”

The second unsigned editorial told readers “It is not how long we live, but how we live that counts…in these times, when so many hearts are overwhelmed with sorrow because of the loss of our dear ones, let them ponder deeply over the words of the prophet and they will find in them the thought that is healing and strengthening. The grief that looks down into the grave will then look up unto the heavens.”

Dayton Jewish Observer Editor and Publisher Marshall Weiss is also project director of Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, under the auspices of the Jewish Federation of Greater Dayton.

To read the complete September 2020 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.