The three small Jewish communities of Richmond, Indiana

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Nearly every seat in Beth Boruk Temple’s 100-seat sanctuary was full: a rarity these days. It was the first bar mitzvah at the Richmond, Ind. congregation in more than a decade.

The dozen or so congregants here in Wayne County just across the state line from Ohio sat among out-of-town guests from Dubai, Colorado, Florida, Oklahoma, and Texas.

On this Shabbat morning last May, 13-year-old Ozzie Lobel was called to the Torah for the first time. Ozzie and his family are new arrivals in Richmond.

“Before I moved to Richmond, Ind., I lived in Boulder, Colo. and we moved almost halfway through my bar mitzvah training, so I had to restart,” Ozzie said in his speech.

“I am here, and I did it with nine months of experience. In Boulder, I wasn’t really learning anything in my bar mitzvah program, but after we joined Beth Boruk and I started training with Gordon, I got a lot more done in a month than I did the whole time in Colorado.

“The reason why is Gordon got straight to the point and taught me everything I need to know. Now I have the tools to choose what I want to do in my future. I learned Hebrew and many prayers, and I understand Judaism a lot more. My Jewish identity is strong and I want to pass that along to my own kids someday.”

Gordon Thompson, retired for more than 20 years from his career as an English professor at Earlham College, has trained generations of students at Beth Boruk for their bar and bat mitzvahs. Ozzie calls him the GOAT, the greatest of all time. “I think Gordon is a very charming guy,” Ozzie added.

Ozzie would come by Gordon’s house each week to study. Gordon’s wife, Mary-Anne, a retired Richmond High School English teacher, always had snacks at the ready.

Gordon himself grew up in Boulder as a non-Jew. He fell in love with and married Mary-Anne from Kenosha, Wisc., who is Jewish. He agreed their children would be raised Jewish.

“After a couple of years of attending services and not being very interested, I started listening and got more interested and converted,” Gordon said. “We wouldn’t have come here if there hadn’t been a synagogue.”

When the Thompsons arrived in Richmond in 1966, Beth Boruk Temple had been open three years.

Kathie and Bob Burton, who arrived in 1965, wouldn’t have moved to Richmond without a temple either.

The parents of brothers Don and Larry Simkin made the move to Richmond in 1960 when the temple was in the works. Don and Larry are retired attorneys.

“One or two years, we all went to Dayton,” Don said. Some of Richmond’s Jews would worship and enroll their children at Beth Abraham Synagogue, Beth Jacob Congregation, and Temple Israel, a 40-mile drive east.

“Then we would have services in a store downtown (in Richmond) or at someone’s home. They would have High Holiday services sometimes in a hotel.”

The Thompsons, the Burtons, Don and Linda Simkin, and Kathy and Larry Simkin are the last remaining couples in their friends group of Beth Boruk families going back to the 1960s.

“We’re very close, the congregation, because there’s not many of us and we’ve been here a long time,” Don said.

Their children have for the most part moved to larger cities.

They recall a membership of about 50 to 60 families at the Reform temple when they arrived in Richmond. Today, about 20 families comprise the local membership roster.

“We all knew each other’s kids,” Gordon said.

“The sisterhood was very active in promoting various activities, including rummage sales,” Bob, also a retired attorney and former city judge and city attorney, remembered. He shared that at 87, he is now the temple’s oldest member. “But more importantly, theater trips. The ladies would organize a trip to either go to Dayton or Cincinnati for food and theater — and serving alcohol on the bus. Kathie, in particular, became very close to all these girls. She had a couple of illnesses, and they were magnificent in helping her out. Sad to say, most of these people are gone.”

Kathie, an RN who taught nursing, said her family was blessed to have the temple.

“It’s been a big part of our lives. I had all these ‘older sisters,’ and our kids had all these honorary aunts and uncles who were so wonderful to us. Our kids talk about going when they were little and they’d be on the floor with their blankets during the service, sucking the thumb.”

“Kathie is a convert because my mother loved her and because Kathie loved my mother,” Bob said. “Kathie went over to the mikvah (ritual bath) at Dayton, which pleased my mother.”

Larry, who has served as Beth Boruk’s president for so long it’s now a permanent position, was a freshman at Indiana University when his family moved here. His brother, Don, was in fifth grade. Don and Bob were in practice together; Bob’s son David would also join the practice.

“Most of the members were merchants downtown,” Don said. “There were three Jewish-owned scrapyards. And not a lot of professionals. We’ve always had four or five Jewish professors at a given time. And we still do.”

Bar mitzvah boy Ozzie’s mom, Rebecca Wartell, moved her family to Richmond in 2024. She’s chair of Jewish studies and an assistant professor at Earlham College. Her Ph.D. in history from Monash University in Melbourne, Australia focused on the formation of the Sephardic diaspora in the Mediterranean in the wake of the Spanish Inquisition and the expulsion of the Jews of Spain. She received her master’s in theology from Harvard Divinity School.

As an outgrowth of her family’s business, Rebecca is also a registered gemologist and gemologist appraiser.

Since her arrival at Earlham, she’s taught the Modern Jewish Experience; Creation, Gender, and Sexuality in Judaism; Jewish-Christian Encounters; and the Jews of Spain and Portugal.

For that course, students helped her with ongoing research using Portuguese Inquisition records available digitally.

“We’ve been mapping data from looking at trial records and trying to understand the trends of the persecution that happened in Portugal in the 16th, 17th centuries,” she said. “Students got really excited about helping with the research and it’s been fun.”

Rebecca also oversees Jewish life on campus, as faculty advisor to the Jewish Student Union and Jewish Cultural Center, one of several residential affinity houses at Earlham.

“It’s not a requirement that they’re Jewish to live there, but they do want to have students that are committed to participating in Shabbat,” Rebecca said. “As a house, they do that nearly every week. And once a month, we’ll host an open Shabbat, so anyone living anywhere else on campus can come to those. It’s student led. So I support them, how they want to do it. Earlham’s a Quaker school by denomination, so they are very excited about doing interfaith programming.”

Gordon was among the prime movers to bring about a Jewish house on campus in 1987 and the Jewish studies program in 1990. In those days, he was the Jewish Student Union’s faculty advisor.

“Gordon’s been super generous with his time,” Rebecca said. She’s joined a longstanding Friday morning Hebrew study group with Gordon and retired professor of Christian spirituality Michael Birkel, a Quaker.

“They’ve been colleagues forever,” she said. “They have read the Tanakh (Jewish Bible) from front to back multiple times in Hebrew.”

Another new member of the Friday morning group, with a year-and-a-half of Hebrew study under his belt, is Earlham School of Religion graduate student Renzo Mejia Carranza, a native of Guatemala.

Jewish studies is a focus of his master’s degree in divinity. A DNA test he took last year indicated he has 30% Jewish lineage on his father’s side, from Italy.

“I realized I was kind of Jewish as well,” Renzo said. “It started to make sense. That’s why I have felt very attracted to Judaism since I was a child.” Rebecca is helping him with his genealogy research.

This academic year, Rebecca has only one Jewish studies minor, Jaxon Roth, a third-year history major from Eaton, Ohio.

“Very early Judaism is very important to inform me of my Christian roots,” he said. “It helps me understand my background.”

Rebecca, who is also the convenor (chair) of the religion department, said that students who major or minor in religion or history take Jewish studies classes, which are cross listed with those departments.

“Quakers are the founders of some of the best liberal arts colleges in the country, and where you have excellent schools, you find a lot of Jewish kids get sent there,” Gordon said. “For most of the time I was at Earlham, Jewish kids were the largest identifiable minority there, more than Quakers, somewhere between 12% and 18% of the student body when they counted those things.”

He said Jewish students came from Philadelphia, New York, Boston, Chicago’s North Shore. Earlham didn’t actively recruit Jewish students, Gordon said; Jewish students and their families sought out Earlham.

“This was in the ’60s and a lot of the connection there was that political Quakers and political Jews had a lot of the same values,” Gordon said. “The Jewish house had nine students living in it and they would have Shabbat dinners every Friday and soon it got so there would be 50 students having dinners at the Jewish house.”

Elie Wiesel spoke at the Jewish house dedication the year after he received his Nobel.

“The Jewish kids were arguing for the house on the basis that there are times when you want to be welcoming, but there are also times when Jews need to be alone with other Jews, especially when things get ugly in the Middle East, to talk about how they felt about things — what they were comfortable with — without feeling pressure.”

From the beginning, the Jewish Cultural Center house also provided a space for non-Jewish students to learn more about Judaism and engage in interfaith dialogue in a Jewish setting.

Earlham’s Jewish studies program, Gordon said, was tied into the Jewish house. “We used the house a fair amount,” he said. “Courses in Jewish studies would have about half the membership of the Jewish kids. Some of the enrollments were huge if the interest was high, if it was a course on the Middle East or on the Holocaust or Jewish feminism.”

Gordon remembered a time when the Earlham community would see an Israeli flag flying from the top of the Jewish house. Those days are long gone on a campus known for left-leaning activism.

The convener of the Jewish house for the last two years is a senior from Northern California. Because of security concerns, he asked The Observer to identify him by his first name only: Khalid, and not to include his photo with this story. Khalid said he knows of only seven or eight Jewish students on the campus; Earlham’s total undergraduate enrollment is just below 700 students.

“We’ve had more Jewish students in the past,” Khalid said. “Even my freshman year, we were 15, I think.”

He added that he’s one of three students who live in the Jewish house, down from six last year.

Khalid double majors in sociology/anthropology and Spanish/Hispanic studies. He took Rebecca’s project-based Jews of Spain and Portugal class and helped with her research.

His studies at Earlham have brought him to Spain and Mexico. In Mexico City last summer, Khalid worked in communications for a nonprofit that, through legislation, protects native corn and other native crops that feed rural communities.

In recent years, Earlham has faced challenges confronting small liberal arts colleges across the country: budget deficits, declining enrollment, steep draws on its endowment, and major budget cuts across the board. Undergraduate enrollment has declined about 42% since 2007.

Khalid said he chose to attend Earlham because it is “really supportive of both academic life and extracurriculars.” He wanted close relationships with professors and leadership opportunities.

“The other thing Earlham does is it provides really excellent financial aid offers,” Khalid said. “I can’t imagine myself anywhere else.”

Because of an “exceptional amount of funding and an exceptional amount of support from faculty,” Khalid said their monthly open Shabbat dinners host 25 to 30 students and faculty members.

“We say the blessings, and we all eat together, and we learn a bit about Jewish customs. And the same goes for traditions like Passover, Sukkot. We don’t usually have Chanukah because that’s during the break. But it’s a really amazing experience to be able to share Jewish customs through food and just build a sense of community on that basis.”

Khalid descends from Ashkenazi Jews on his mother’s side. “My dad’s side are Palestinian Muslims.” He’s also involved with cultural events for Arab and Palestinian students on campus. “Almost every week, I’ll make a Palestinian dish for Shabbat and I’ll share that with my house.”

He describes the Jewish side of his family as secular Reform Jews and the Muslim side of his family as also more cultural and secular than anything else.

“When you’re a kid, the way you see your cultural or religious background is very normal. And then as you grow up, you interact with more people. You find what’s exceptional about it, and you come to appreciate it more. So I think as I’ve gotten older, I’ve come to see and appreciate the beauty in Jewish cultural and spiritual traditions. And I think at Earlham, being able to be in this position, I’ve developed my own connection with it. It is an important part of my life.”

Khalid said there’s an anti-Zionist presence on campus. “I haven’t seen much of a Zionist presence. I think that also reflects a trend in Gen Z of people who think that way, so it’s not anything exceptional compared to the general trend.”

When asked if he sees himself as an anti-Zionist or a non-Zionist, he responded that his family has been in Gaza for many centuries and that they’re still there.

“After Oct. 7 and the land and air siege on Gaza,” Khalid said, “the Israel military forces killed 87 members of my family in Gaza.”

“So I want to see regardless of any label, a future where my family, the family that has been forced to leave, is able to return to their lands, is able to live on the most basic levels, able to breathe and eat and live in peace without fear, and to be able to live in a state with rights to vote for who they want to represent (them) and to live in harmony and peace.”

He said there are no Jewish Voices for Peace or Students for Justice in Palestine chapters at Earlham. Both are anti-Zionist student organizations. “But we do have an unofficial coalition of students that network together on progressive issues.” Earlham’s website lists the student organization Students for Peace and Justice in Palestine.

Since Oct. 7, 2023, Khalid said there have been two vigils on campus focused on mourning, and one demonstration.

“It’s been everybody coming together to mourn, to have dialogue, and to push for the recognition of freedom, dignity, and humanity of Palestinians,” he said.

When asked if anyone on campus expresses empathy for what happened to those in Israel on Oct. 7, 2023, Khalid replied, “We’ve read the names of people who have lost their lives to violence. So there has been a recognition. But I don’t know anyone personally who has a direct connection to the impact of Oct. 7.”

Khalid added that he hasn’t experienced antisemitism at Earlham.

“It’s something we talk about. We talk about antisemitism. We’ve talked about our experiences growing up and various microaggressions that we might have heard growing up…We’re all openly Jewish, people who say, ‘I live in JCC, I love living in JCC.'”

Rebecca shared that flyers promoting Passover and Yom Hashoah events have been torn down from her office door three times. “This is not exactly vandalism, but close.”

Last summer, Richmond experienced a harrowing spate of swatting threats called into law enforcement from a man who claimed to be holding Jewish hostages at the 700 block of East Main Street. He said he was armed with firearms and explosives and had already killed a hostage. The first instance led to a standoff situation for nearly four hours.

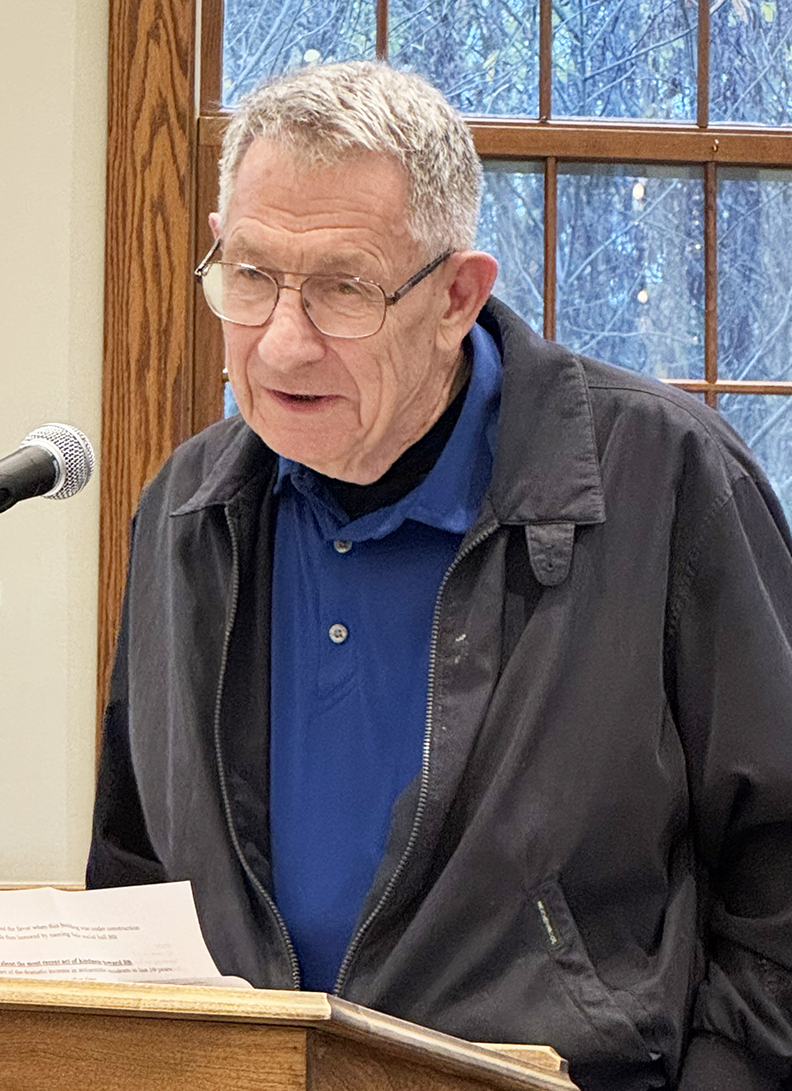

At the Richmond Interfaith Network Annual Golden Rule Gathering held in November at the First Friends Meetinghouse, Gordon shared an anecdote as the representative of the Jewish community.

“As you’re probably aware, there’s been a dramatic increase in antisemitic incidents in the last 10 years. There’s much more vandalism than there used to be, and many more terrorist attacks. So we started hiring off-duty Richmond Police officers. One day, a few years ago, our chief protecting officer turned out to be Mike Britt. Mike was the chief of police at the time.

“For reasons known only to him, Mike turned up more and more frequently to be our guardian. It was clearly personally important to him to keep the Jewish community safe. Pretty soon, Mike asked us to stop paying him. He wanted this to be a gift. After a few weeks of this, well, we couldn’t stand that, so he agreed to let us support his favorite charity, the Richmond Police Department’s Blue Angels Fund.”

The Richmond area was first settled by Americans of European descent when Quakers arrived at the East Fork of the Whitewater River in 1806. There, they would establish Friends United Meeting, Richmond Friends School, Earlham College, and Earlham School of Religion.

Rabbi Lance Sussman — now retired rabbi emeritus of Reform Congregation Keneseth Israel near Philadelphia — compiled a history of Richmond’s Jewish community when he served as Beth Boruk Temple’s rabbinic intern from 1977 to 1980.

According to Sussman, harness and saddle maker William Brady was the first known Jew to settle in Richmond, in 1834. Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise’s German language newspaper Die Deborah noted in 1861 that several Jewish families lived in Richmond. And his American Israelite publication reported that High Holiday services were held for the first time in Richmond in 1869.

Based in Cincinnati, 70 miles southeast of Richmond, Wise was known as the architect of Reform Judaism in the United States. He would establish the Union of American Hebrew Congregations in 1873, Hebrew Union College — the oldest Jewish seminary still in existence in the Americas — in 1875, and the Central Conference of American Rabbis in 1889.

It wasn’t until 1919, in the aftermath of World War I, that Richmond’s Jewish community of about 40 households formally organized, first with a local American Jewish Relief Committee Campaign and then with a sisterhood that affiliated with the National Federation of Temple Sisterhoods a year later.

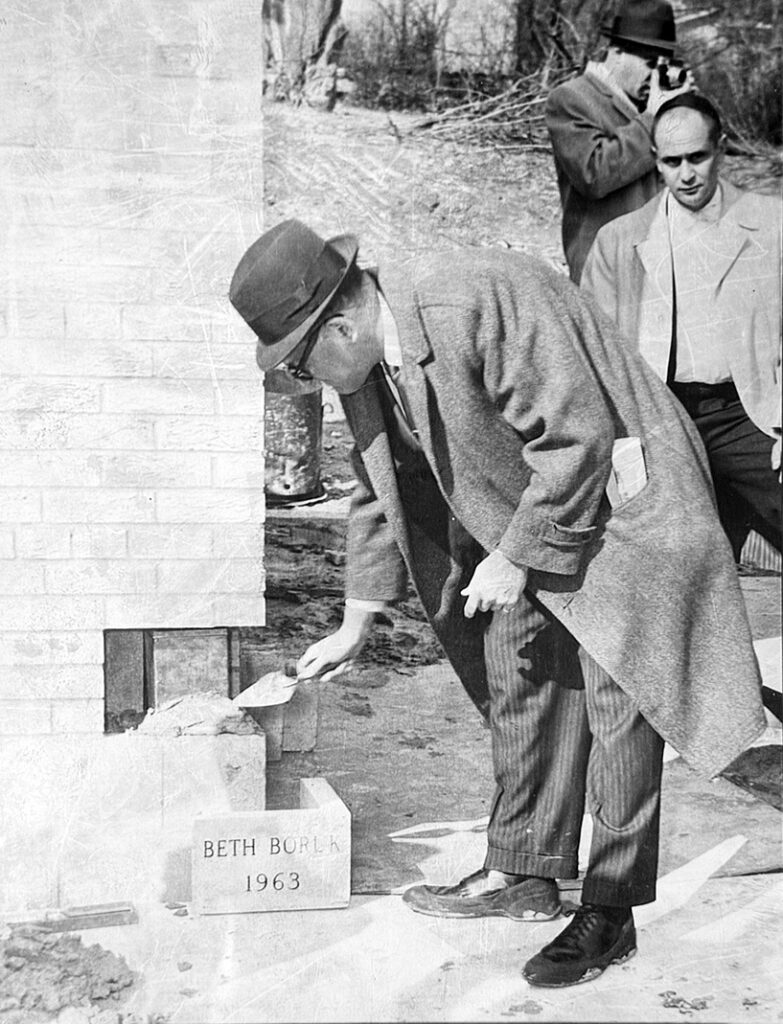

The Jews of Richmond also organized Richmond Jewish Congregation in 1920, led by clothing merchant Sam Fred. Member Abraham Harsh, who owned a coal supply company, donated a Torah. The congregation wouldn’t have its own building until 1963.

For 40-plus years, worship services were held in the back of Jewish merchants’ stores, with High Holiday services and Passover Seders at the Leland Hotel. The sisterhood ran the religious school.

Beginning in 1921, HUC would send rabbis from its staff once a month — and then student rabbis — to lead services for Richmond Jewish Congregation.

When the State of Israel was established in 1948, the Jews of Richmond founded the Richmond Jewish Council and its Jewish Welfare Board Campaign. The men organized a local B’nai B’rith chapter in 1955 with 32 members, and in 1971, the temple purchased a section of Earlham Cemetery for congregant burials.

Sussman noted that when temple construction got underway in 1962, members debated whether to align with Reform or Conservative Judaism.

Late in 1963, the congregation decided to “nominally” affiliate with the Reform movement; HUC then expanded its student rabbi program with Beth Boruk Temple from once a month to twice a month.

In his history, Sussman also puzzled over the temple’s unusual name, Beth Boruk, as grammatically incorrect Hebrew. The Palladium-Item newspaper reported at the temple’s cornerstone laying ceremony that its name meant House of the Blessed.

“Boruk or baruch is a proper adjective (blessed or praised), making Beth Boruk a nonsensical phrase: House of Blessed,” Sussman wrote.

One theory Sussman put forward is based on a story that the temple was named in memory of Bruce Glazer, using his Hebrew name. The son of then temple president Bert Glazer and his wife, Rosalie, Bruce died in a childhood accident at the family’s home.

Just as HUC in nearby Cincinnati has had a significant impact on the trajectory of Richmond’s Jewish community, so too have the Quaker institutions in its midst.

Quakers in the United States were actively involved in rescuing thousands of Jews from Eastern Europe during the Holocaust, via the American Friends Service Committee and similar groups that worked with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee.

One such refugee, Norbert Silbiger, an Austrian Jew, founded Richmond Civic Theater in 1941.

“The story I like best,” Gordon shared, “is that First Friends, when they had their building downtown, they let the Jews have services there before the temple building was finished in 1963.”

Beth Boruk Temple returned the favor when First Friends was between buildings.

As a thank-you, First Friends named the reception hall at its new meetinghouse in honor of Beth Boruk.

Jews and Quakers in Richmond, as across America, also worked together in the civil rights and anti-war movements.

In the second half of the 20th century and continuing to this day, Jews and Quakers generally split on issues related to Israel and the Middle East. The American Friends Service Committee is staunchly critical of Israeli policies and has promoted the Boycott, Divestment, and Sanctions movement.

Gordon said Earlham “let the ball drop” in terms of Jewish student enrollment. “The number of Jewish students is far less than it used to be.” One reason, he said, is the active pro-Palestinian climate on campus.

A major turning point in Jewish admissions, the retired Earlham professor said, came about in 2012 when student activists tried to get the college to boycott Sabra hummus, which at the time was co-owned by an Israeli company.

“They just went and told the director of the food service that she needed to remove that,” Gordon said. “And as soon as she did, they went and notified the national organization Students for Justice in Palestine that Earlham was observing BDS. But by the afternoon, as soon as the administration heard about that, they said, ‘Absolutely not, we are not.’ But already, the national organization had announced it.

“Well, that stuff is lethal. Jewish parents pay attention to that. And whatever your opinions are of the Middle East, we don’t want to go to a place that’s hostile.”

Gordon said almost all the stories he has of Jewish and Palestinian students over the four decades he taught at Earlham are happy ones.

Since 1869, Quakers in the United States have funded the Ramallah Friends School, a K-12 private school in the West Bank. Until recent budget cuts, Earlham provided fellowships for Ramallah Friends School graduates to attend Earlham.

He remembered Jewish and Palestinian students sharing a campus van to get to HUC in Cincinnati: the Jewish students went to hear a guest speaker, and the Palestinian students went to protest outside. “These were all friends.”

Gordon and Mary-Anne’s son David, an Earlham graduate — along with members of the Vigran family, who grew up at Beth Boruk Temple — have endowed a new scholarship this year, the Elizabeth Thompson Jewish Studies Scholarship, in memory David’s sister, Gordon and Mary-Anne’s daughter, who died in 2007 at the age of 35. Its aim, Gordon shared, is to recruit Jewish students.

An unexpected turn in Richmond’s Jewish community has been the arrival since 2020 of about two dozen Satmar Chasidic families from Brooklyn. They moved to a subdivision in Centerville, Ind., just west of Richmond.

At the time of the Covid outbreak on the East Coast — when the Orthodox Jewish community in New York was hit hard from mass Purim celebrations in March 2020 — Don received a call at his law practice.

“They wanted to buy all the unused lots in a subdivision in Centerville,” Don said. He helped them purchase a farmhouse in the town of about 2,770 people where they would build a mikvah.

Don asked the caller from Brooklyn why he picked Centerville, Ind., beyond the much lower cost of living. “He said, ‘Well, it’s getting a little too liberal here for us.’ That’s a funny thing to hear from a Jewish person. They like parochial schools with state funding. I think that was enticing to them. They eventually bought all these lots, and anytime someone else in the development would sell an existing home, they would buy it too.”

Satmar is the largest Chasidic sect in New York and worldwide. Its adherents keep to themselves, espouse ultra stringent religious observance, and hold vehemently anti-Zionist views based on their religious beliefs.

This fall and winter, Satmar leaders in New York, for example, threw their support behind mayor-elect Zohran Mamdani, a self-described anti-Zionist.

“They don’t want anything to do with us,” Bob’s brother, Larry, added of the Satmars in Centerville.

It’s the opposite of what Jews in Richmond have experienced when a Chabad rabbi from Indianapolis regularly visits them. He comes over to supervise kosher certification at the Richmond Baking Company.

“We’ve had quite a bit of contact with the Chabad rabbi in Indianapolis,” Gordon said. “The Lubavitchers come over quite often and they’re tremendously outgoing. I find them kind of sweet.”

In addition to the new Satmar shul (Congregeation Kahal Centerville) and mikvah in Centerville, the organizer of the community, Aron Majerovic, has set up Bikur Cholim of Centerville to provide kosher food and lodging for Orthodox families at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center, Bnos Ani Chomah Centerville to aid impoverished Jewish families cover their educational expenses, and Indiana-based LLCs Centerville Kosher, IDF Properties, and Majer Management.

Despite attempts to contact Majerovic via phone, email, and mail, he did not respond to requests to be interviewed for this story.

“As far as I know, they’re thriving,” Don said of the Satmars in Centerville. “So it’s worked out, I guess. Sometimes you’ll see them at the grocery store.”

Rebecca said the first time she heard Yiddish spoken at Richmond’s Dillard’s, she did a double take.

Larry and Don drove me to the subdivision where the Satmar families live in the hopes that The Observer might interview some residents. A young man who wore a tallit katan (little prayer shawl garment) stood in front of his house.

On his garage was a large, handwritten sign. It read: “We are Jews, NOT Zionists! The state of Isreal does NOT represent the Jewish People. Toreh demands: Give back all Palestine to Palestinians!” The sign included the Palestinian Authority flag in one corner, and the flag of Israel crossed out in another.

I approached the man, identified myself, and asked if I could interview him about why his family moved to Centerville. With his wife and young children watching from the doorway, he declined. He said he didn’t trust news media. He confirmed they were Satmar and gave his approval for the sign on their garage to be photographed for this story.

With the addition of the Satmars in Centerville, the 2025 American Jewish Year Book estimated the Jewish population of Wayne County, Ind. at 180 people out of a total estimated general population of 66,410.

Ozzie’s bar mitzvah quietly marked a major change for Beth Boruk. For 102 years, student rabbis from HUC in Cincinnati came up to lead services. His bar mitzvah last May was the final service led by an HUC student rabbi, Gretchen Johnson.

HUC will close its rabbinic ordination program in June 2026 at its Cincinnati campus — it’s oldest — in favor of its New York and Los Angeles campuses.

“Generally, we got them for two years if we were lucky,” Bob said of HUC rabbinic interns. “We’ve had some for three. We’ve been very lucky over the years and had services primarily every couple of weeks.”

“I don’t see much concern on the part of the Reform rabbinic movement to do anything about these small Midwest congregations that have relied on HUC,” Kathie said.

“And I don’t think they care. I think that’s terribly sad, because the future of Judaism rests on these small congregations and it’s hard.”

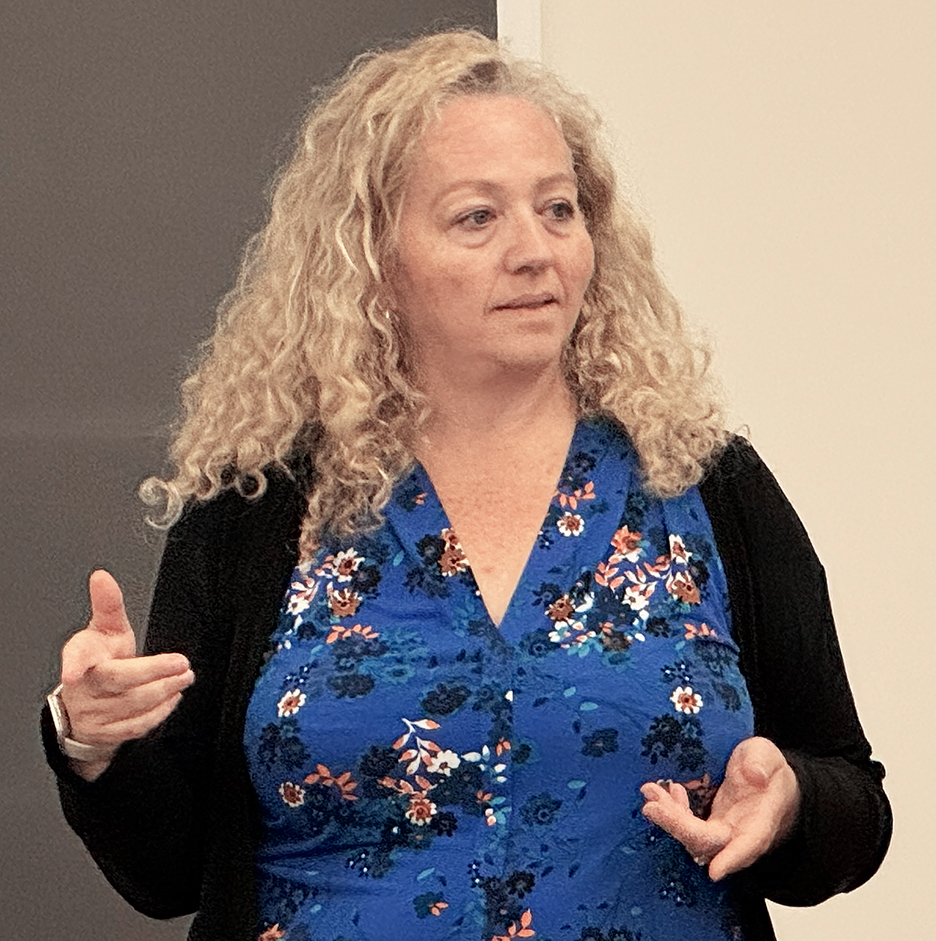

Cantor Andrea Raizen, who retired from Beth Abraham Synagogue in Oakwood, Ohio (just south of Dayton) in 2024, led this year’s High Holiday services at Beth Boruk. She now leads its monthly Friday night Shabbat services.

As always, Mary-Anne calls everyone on the local membership roster a few days before each service to remind them to attend.

“The temple’s paid for,” Bob said. “It’s beautiful. We love it. It’s not necessarily a financial challenge. It’s a people challenge.”

“We’ll keep this running as long as we can,” Larry said. “I thought 20, 30 years ago it was going to fold, but it hasn’t. We still have new people every year. I will donate and I think other people will. That’s not going to be a problem.”

To read the complete January 2026 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.