Much of book about TR & the Jews resonates today

By Martin Gottlieb, The Dayton Jewish Observer

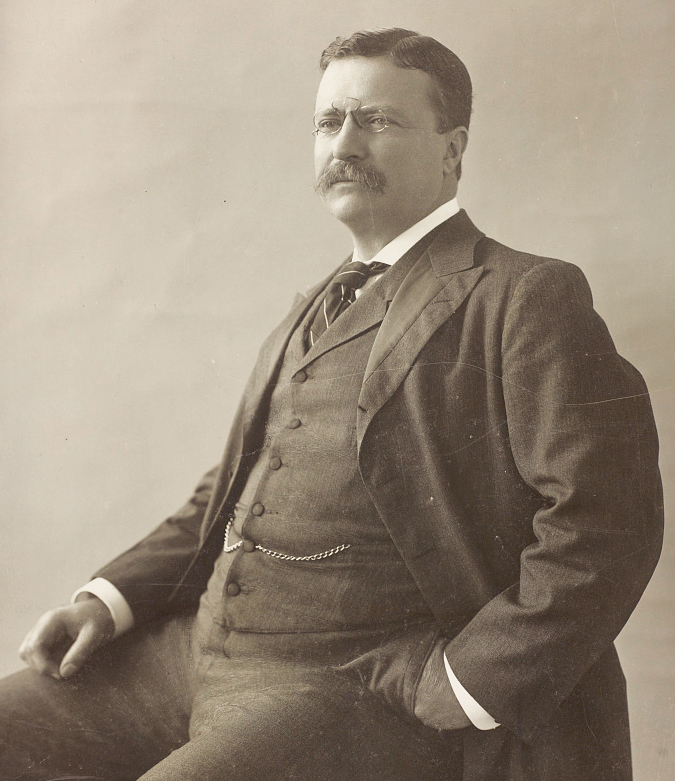

Some people, when they hear that there’s a book about Teddy Roosevelt and the Jews, are surprised: A whole book? Who knew there was enough material? TR is known – to history buffs, at least – for his activity in many policy realms. But Jewish issues?

Well, there is such a book, and the author says there’s another one coming. The first one goes through Roosevelt’s presidency. The second will pick up there.

Author Andrew Porwancher is a professor at Arizona State University who has something of a niche in surprising Jewish presences in American political history. He’s the author of The Jewish World of Alexander Hamilton.

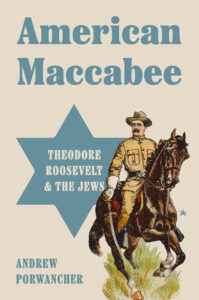

Porwancher’s new book is titled American Maccabee: Theodore Roosevelt and the Jews. (Princeton, 2025). This is a reference to TR’s admiration of the Maccabees as a fighting people. Whereas others in his time saw Jewish men as lacking in physical strength and courage, TR saw the physiques and health problems of Jewish men as resulting from the lives they had been consigned to in Europe. When he looked at them, he saw potential Maccabees.

TR was a politician in New York City during the early stages of development of the Lower East Side as a Jewish world. Then he was president when pogroms in the Russian empire became a big international issue. So Jewish issues were always present.

From the beginning, Roosevelt was a friend of the Jews, out of both political calculation and sincerity, Porwancher believes. Appalled by the extreme poverty of the Lower East Side, TR was a big fan of photojournalist Jacob Riis, who documented that poverty in his seminal book, How the Other Half Lives. Roosevelt, unlike some others, didn’t see the poverty as somehow the fault of the Jews. He was a reformer even as police commissioner (an appointive role).

Much of the book resonates today. Porwancher uses the modern term “identity politics.” TR was determined to appoint Jews to positions they had hardly ever had, including police jobs. He appointed the first Jewish cabinet member.

And he pointed with pride to these appointments. He insisted that he was only interested in treating everybody equally. But he wanted Jewish appointees, and he wanted Jewish voters to know about them.

The bulk of the book is about President Roosevelt’s response to Russia’s pogroms. Here, it bogs down. One problem is that the options TR considers don’t seem very fateful. Invasion wasn’t a real option. Trade embargoes weren’t. Sanctions weren’t. Pulling the ambassador wasn’t.

The issue always seemed to be only whether to send this or that angry note.

That got hotly debated, because custom held that countries should stay out of each other’s business, and because the U.S. had it own embarrassments with Jim Crow and lynchings.

Actually, TR didn’t seem much bothered by the latter point; he insisted – incorrectly, says the author – that the number of lynchings didn’t come anywhere near the number of deaths in the pogroms.

Setting aside Russia, much here is striking. Democrats and Republicans are always competing for the votes of the Jews. Nobody seems to worry much about any backlash, about losing the votes of other groups as a result. Antisemitism was common, of course, but apparently not much of a political force.

Appealing as TR’s connection to Jews is to modern Jews, the book does not leave one with a warm glow. There’s also – not pervading the book, but sort of haunting it – the matter of race. On that, TR’s enlightenment did not prevail. He did not fight the fight that also needed to be fought.

Retired Dayton Daily News editorial writer Martin Gottlieb is advisor to The Dayton Jewish Observer.

To read the complete September Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.