Dayton Hungarians highlights significant Jewish connections

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Of the hundreds of interviews Mike Sakal conducted over three decades for his just published two-volume book, Dayton Hungarians: Their Stories, Glories and Folklore, it was Rose Vegso’s that set the tone for the project.

Vegso came to the United States from Hungary in 1921 as a young woman. She lived on North Broadway and then on Williams Street.

When Vegso was well into her 90s, Sakal asked her why she had come to America.

Her reply: “We came to America to work, worship, eat, dance, and love.”

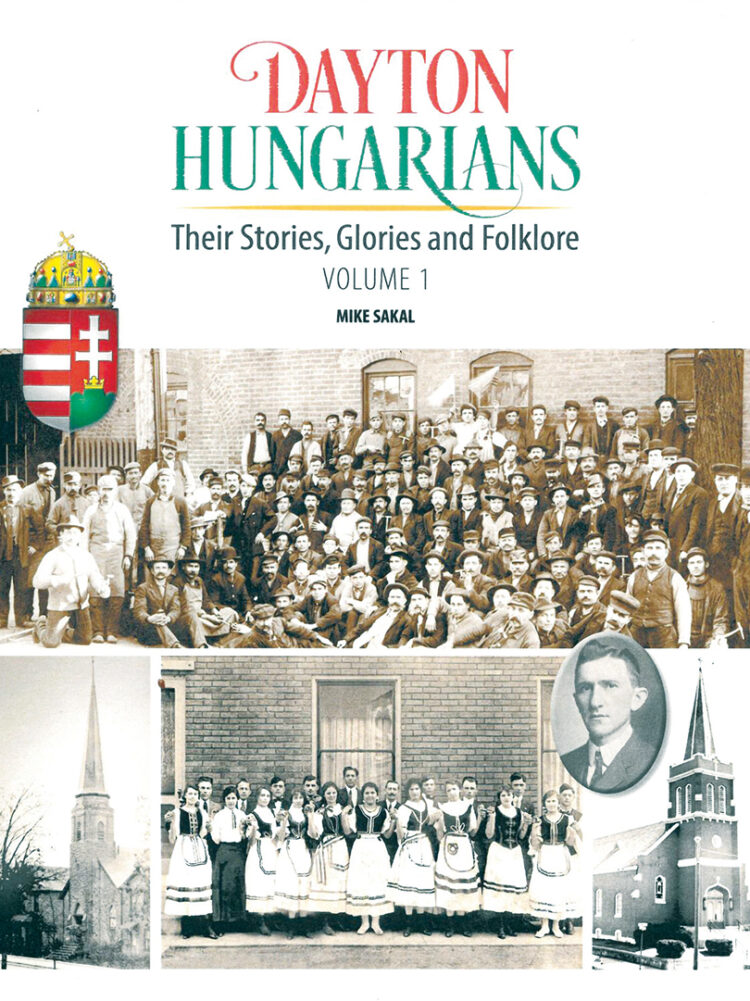

Through numerous photos, anecdotes, oral histories, and years of painstaking research, former journalist and public affairs professional Mike Sakal has definitively documented the origins, development, and continuing experiences of Dayton’s Hungarian community.

Dayton Hungarians is encyclopedic. The volumes come in at 846 pages. It’s a gift to the estimated 6,000 people in the Dayton area with Hungarian lineage, and to all with a passion for Dayton’s history.

The finished product also marks the final project of Dayton’s last remaining Hungarian church before its official closure.

The Old Troy Pike Community Church, formerly the Hungarian Evangelical and Reformed Church of Dayton, funded Dayton Hungarians’ publication.

“The Reformed Church was waiting to wrap this book up to formally close,” Sakal said. “They were down to four members. I told them about this book. They said they wanted this to be their legacy.”

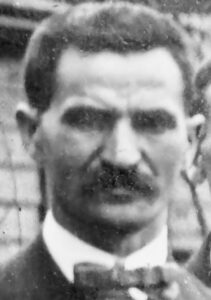

Sakal’s history cites Hungarian Jewish labor contractor Jacob D. Moskowitz as the person who brought about Dayton’s organized Hungarian communities.

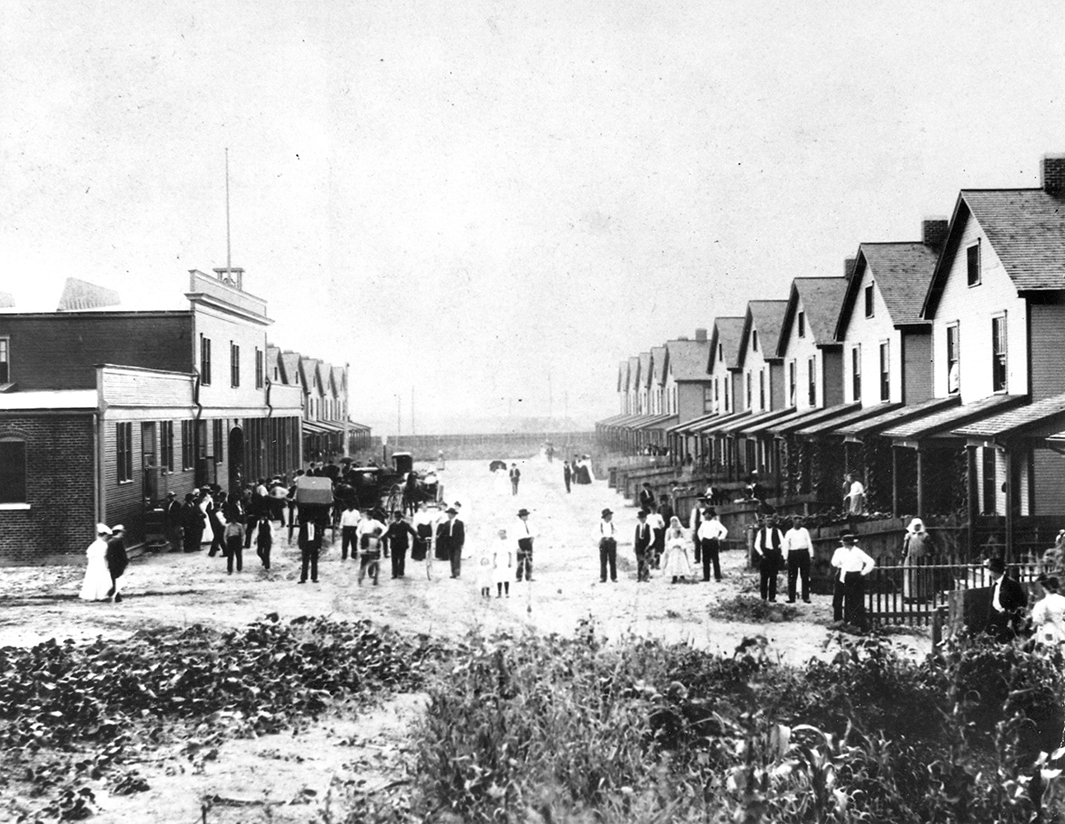

Moskowitz started a colony of Hungarians in 1898 on the West Side for the Malleable Iron Works. In 1906, he opened another Hungarian colony, in North Dayton, for the Barney and Smith Car Works.

Sakal digs deep into the controversy that surrounded Moskowitz in his day and for generations since. Residents of Moskowitz’s North Dayton Kossuth Colony, named for a Hungarian hero, remembered Moskowitz alternately as a benevolent father figure and an employer who exploited his laborers.

The Kossuth Colony was self-contained behind a 12-foot-fence, with a church and stores. Workers were paid in tokens for redemption at colony stores.

If workers or their family members bought goods outside the colony that were available for purchase inside, the worker was dismissed and their family expelled.

The controversy played out in Dayton’s daily newspapers.

Moskowitz himself built the Hungarian Reformed Church inside the Kossuth Colony fence, for colony residents. He also donated a stained-glass window to Holy Name Church in West Dayton.

“A lot of people in North Dayton seemed to think, ‘Yes, he gave us a place to live, he helped us get over there,” Sakal said of what he learned about Moskowitz from interviews. “And, of course, a lot of people paid him back over time for that trip. He painted this rosy picture for these people. And they came, they worked hard, these long hours, and sat on their front porches in the evenings and smoked their long pipes, and made their wine, and butchered their hogs.”

Sakal also profiles three other Hungarian Jews in Dayton Hungarians: Sam and Ralph Rubenstein, and Julius Leopold.

Samson “Sam” Rubenstein opened his clothing business on the 1000 block of West Third Street in 1897. Sakal described him as a “savior” to Dayton’s Hungarians.

“The immigrants that would come over, sometimes they wouldn’t have that extra money for the clothes for kids,” Sakal said. “They would give them the clothes (on credit) until they could pay them back.”

Sakal interviewed the late Ralph “Ruby” Rubenstein, son of Geza and Sam Rubenstein, who worked in the store from the age of 6 in 1917; he sold Rubenstein’s in 1986.

Julius Leopold was the manager of the Hungarian Clubhouse and Saloon and ticket agent for Cunard Steamship Line. Leopold was president of the Hungarian Grocery and Meat Market co-op, Leopold’s Hall and Saloon, owner of the Mecca Theater, and publisher/editor-in-chief of Daytoni Magyar Hirado (Dayton Hungarian Herald) newspaper.

Leopold was born to Jewish parents in the Habsburg Empire, though it’s unclear if he lived as a Jew in America.

Jewish readers will be interested to learn about Hungarian Frank Riesinger, a non-Jewish funeral director who handled funerals for members of Dayton’s Jewish community in the first third of the 20th century.

Dayton Hungarians, $75, is available for purchase at New & Olde Pages Book Shoppe in Englewood and the Carillon Historical Park Museum Store in Dayton.

To read the complete August 2025 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.