Irreplaceable Ira

Though overshadowed by brother George’s music, his lyrics are here to stay.

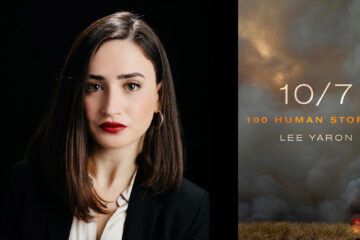

Book Review by Martin Gottlieb

Special To The Dayton Jewish Observer

Ira Gershwin never built the Stairway to Paradise that he imagined in his 1922 lyric. Perhaps he would have if his brother – composer George Gershwin – had not died young. After that, Ira went on to sustain his own legendary career. But he never seemed to be happy.

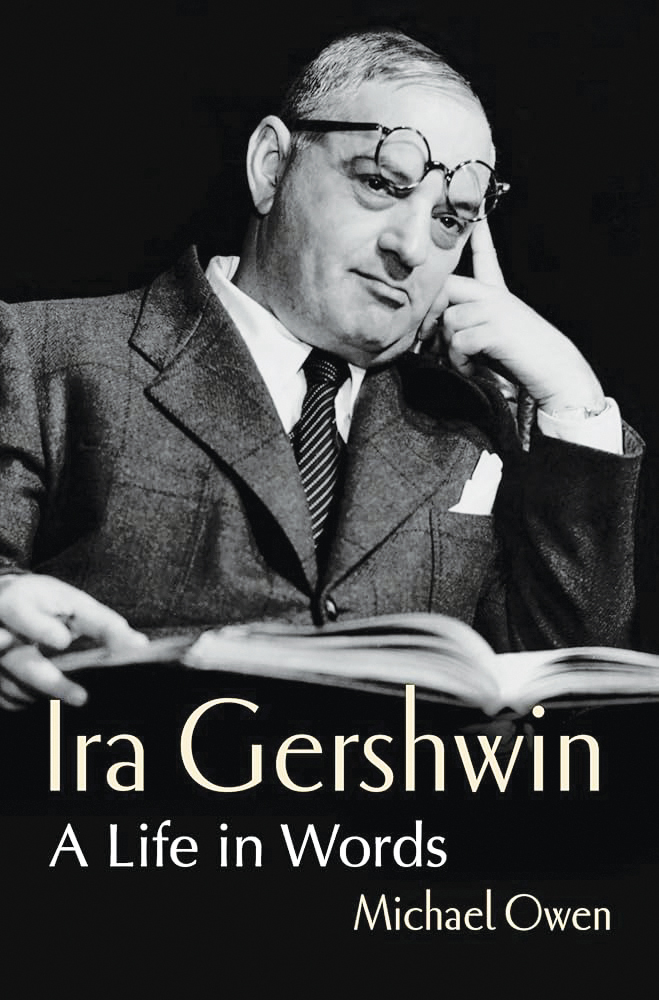

Ira and George grew up deeply assimilated in early 20th century New York. In Ira Gershwin: A Life in Words (Liveright Publishing, 2025), author Michael Owen tells a story into which their Jewishness hardly figures. They were less Jewish Americans than melting pot Americans.

Fortunate to be in an entertainment mecca and blessed — at least in the case of George — with monumental talent, they almost inevitably found their way into show business. For Ira, the path had detours and frustrations, but his brother ultimately came to value him as a lyricist. And they were on their way.

But George’s death at 38 of a brain tumor had a much more profound effect on Ira’s life than to deprive him of a beloved brother and a partner; partners were not hard for Ira to find.

The death shaped the rest of Ira’s life, saddling him with much (and disputed) responsibility for handling George’s legacy, his papers, his unpublished work, and the ongoing financial arrangements for the money coming in that would have been George’s.

The legal and family battles (which were conjoined) were endless and enervating and do not make for a good read.

This new bio did get a good review from the New York Times: “dignified but not starchy, efficient but not shallow, and honest about grief’s unrelenting toll.”

But readers might not find the book as entertaining as they had hoped.

Still, there are items of interest here. For a remarkably accomplished person (a Pulitzer Prize winner, a three-time Academy Award nominee, contributor to multiple Broadway hits and some movies, among innumerable other accolades), Ira was remarkably lazy. He frequently turned down projects just because he didn’t feel like doing the work.

When he did get involved, though, he’d be industrious. One gets the impression his work emerged from a sense of obligation to his collaborators. Conscientiousness trumped laziness.

He never felt he got out from under his brother’s shadow and never felt he deserved to.

He never made the transition to writing stand-alone songs or even movie themes. He had to have a show, a story.

And there were plenty of Broadway and movie flops, not to mention projects that never came together despite early enthusiasm.

But we do have Fascinating Rhythm; Oh, Lady Be Good; Someone to Watch Over Me; The Man I Love; Strike Up the Band; ‘S Wonderful; How Long Has This Been Going On?; I’ve Got a Crush on You; Bidin’ My Time; But Not for Me; I Got Rhythm; I Got Plenty ‘o Nuttin; It Ain’t Necessarily So; Let’s Call the Whole Thing Off; They All Laughed; and A Foggy Day (in London Town), among so many others.

The new Owen book might be of most interest to intense aficionados. It provides a play-by-play account of the development of various staged musicals.

For most readers, the best Gershwin read might be the lyricist’s words themselves. He put together his own collection of his work, called Lyrics on Several Occasions (1959), with commentary. He was an engaging writer of prose, too. Also, there’s a thick coffee-table book called The Complete Lyrics of Ira Gershwin (1994), edited by Robert Kimball.

Then, too, Michael Feinstein, the singer and student of the genre, called “The Great American Songbook,” whom the bio mentions briefly, did his own book about his intense connection with Gershwin. At the end of the lyricist’s life, Feinstein did a deep dive into Gershwin’s archives and wrote The Gershwins and Me (2012).

To read the complete March 2025 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.