Survivor Robert Kahn dies at 100

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Not only did Holocaust survivor Robert Kahn make it to 100 in September, into the last year of his life he continued to share his testimony in public and classroom settings — standing up when speaking — and was present at Jewish War Veterans events as one of the few remaining World War II veterans in the Dayton area.

Kahn died peacefully, surrounded by his family, at Hospice of Dayton on April 2.

A pacifist at heart, Kahn dedicated much of his life in Dayton to nurturing interfaith relations in Scouting, and in his later years, to imparting the lessons of the Holocaust for all who wanted to listen.

More than a generation of area schoolchildren knew him as the boy the Nazis forced to play the violin on Kristallnacht in Mannheim, Germany while they beat his father with clubs, ransacked the family’s apartment, and burned their possessions.

He, his parents, and sister ultimately managed to escape. Eighteen members of their family did not.

“I’ve made an effort throughout my life, especially with the family — my wife, Gertrude, my children, my grandchildren — to talk as little about it as I could,” he said in a 2017 interview with The Observer.

But his children and grandchildren kept asking him for details. That was when he began to write his autobiography. And through it, to try to process his traumas.

Kahn would conduct meticulous research on his 18 family members who were murdered in the Holocaust.

“It was very important to me that I find out as much as I could about them, at least in their final hours,” he said. “Otherwise, their names would be lost, their lives would not be remembered, and my children and grandchildren would never know about it.”

It wasn’t until Kahn reached his 60s that he began giving talks about the Holocaust. Each talk opened an emotional wound. But he felt obligated to do so.

“When you talk about it, it comes back to life.”

The impetus to find his voice had arrived in a package. The caretaker of the house where he used to live in Mannheim sent him the violin from his youth; it had been hidden in the house all those years.

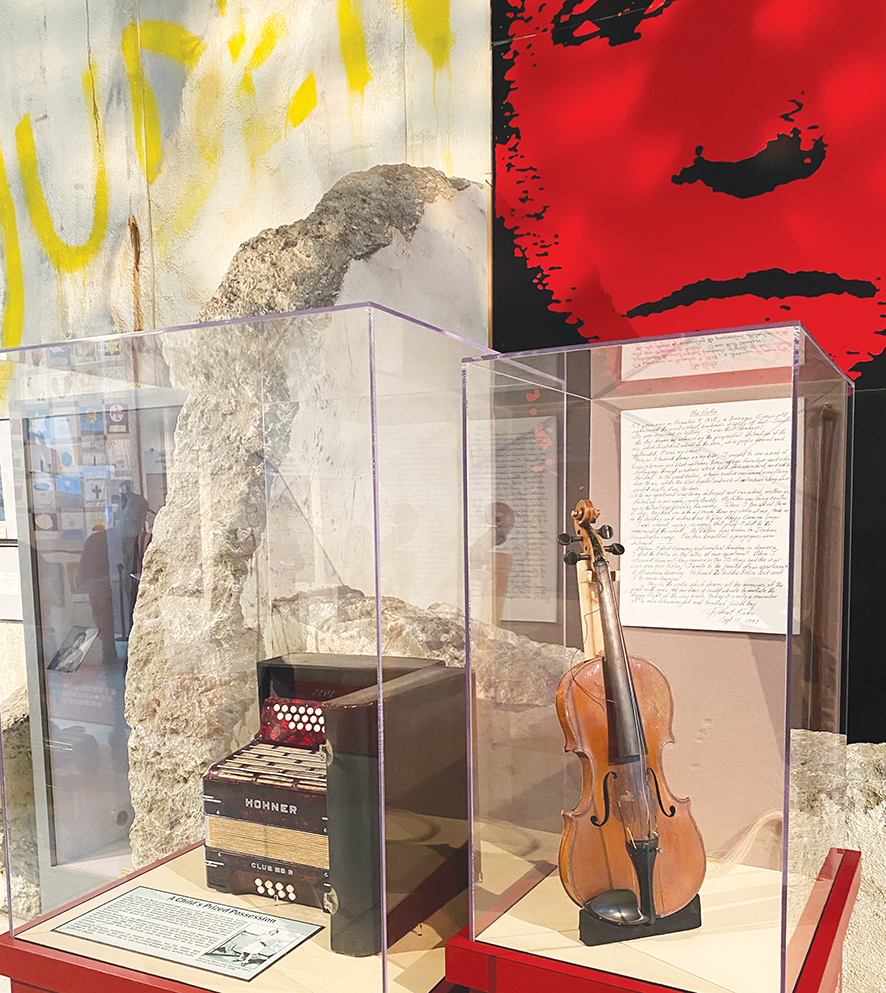

That violin, which Kahn was forced to play on Kristallnacht, is on display with the Prejudice and Memory Holocaust exhibit at the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

Next to it is the accordion his wife took with her as a child when she was rescued from Nazi Germany on a Kindertransport to England.

Kahn spoke to thousands of middle and high school students when their classes visited the exhibit, and at their schools.

But it wasn’t until he reached the age of 93 that he shared another story of his encounter with Nazis. This, he related with the completion and publication of his autobiography, The Hard Road of Dreams: Remembering Not To Forget. Kahn had worked on it for 27 years.

In The Hard Road of Dreams, he revealed that after his service in the U.S. Army Air Forces in the Pacific, Kahn came to Wright Field in 1946 to work for Operation Paper Clip — the U.S. intelligence and military program that brought German scientists to work for the U.S. government at the end of World War II.

“It was top secret. It had to do with German scientists that were brought over for picking their brains in regard to what they were doing. My job was to interrogate some of them,” he told The Observer.

Of the more than 1,600 German scientists brought to work for the U.S. government through Operation Paper Clip, 86 aeronautical engineers were sent to Wright Field.

“I hated those guys, and it was kind of difficult to work with them and not show my dislike for them and the work that they did,” he said. “I found out much about the scientific experiments they had performed using human beings as test vehicles. And these test vehicles were, in most cases, Jews.”

The German scientists didn’t talk to Kahn about those experiments; he read about them in the captured documents that were available to him.

He said their experiments in Nazi Europe were carried out to determine the ability of pilots to withstand extreme conditions such as hypothermia and submersion in water.

“Many of the test subjects never made it through the experiments,” Kahn recalled.

After two years, and with most of the scientists sent to other locations, Kahn transferred to work on the base in procurement and resources. He retired from Wright-Patt in 1985.

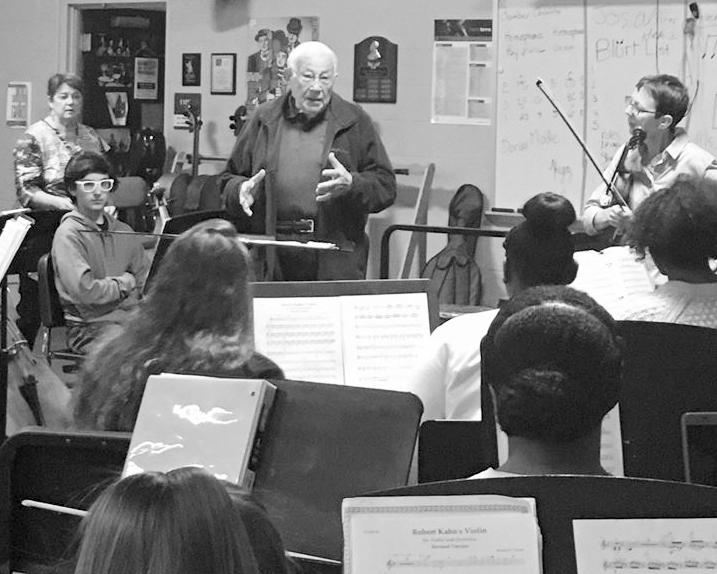

Kahn’s violin inspired one composer to write a work for symphony orchestra and violin soloist about it. Niccolo Athens, who now teaches composition at the Juilliard School’s Tianjin, China branch, was so moved when he saw Kahn’s violin at the Air Force Museum that he wrote the piece Bob Kahn’s Violin. It had its world premiere in Dayton, with the Stivers School for the Arts Philharmonic Orchestra and Dayton Philharmonic Orchestra violinist Betsey Hofeldt on Nov. 8, 2017 — 79 years after Kristallnacht.

Gertrude and Robert Kahn were married for 75 years when she died in 2021. He then focused on another Holocaust project. Kahn and one of his granddaughters sponsored and obtained approval for Stolpersteine — memorial plaques paved at the last address of Holocaust victims — to be placed in Mannheim for friends of his family from his youth.

He and his granddaughter also began the process to place 18 Stolpersteine in cities across Europe in memory of their family members who perished at the hands of the Nazis.

“Because I survived their fate, I made an oath that I would devote my life to sharing with the world how and what happened during the Shoah,” he explained.

The family will hold Kahn’s funeral service at 3 p.m., Sunday, April 7 at Temple Israel.

To read the complete May 2024 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.