DeMille’s silent Ten Commandments at 100

The first biblical epic’s Jewish connections go surprisingly beyond the obvious

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

In the early 1980s, a group of amateur archaeologists discovered the remains of the City of Rameses buried beneath dunes of sand. Over a period of 30 years, with significant fundraising and help from a professional archaeologist, they would excavate such artifacts as the head and limbs of a sphinx, pieces of statuary, coins, and even bottles.

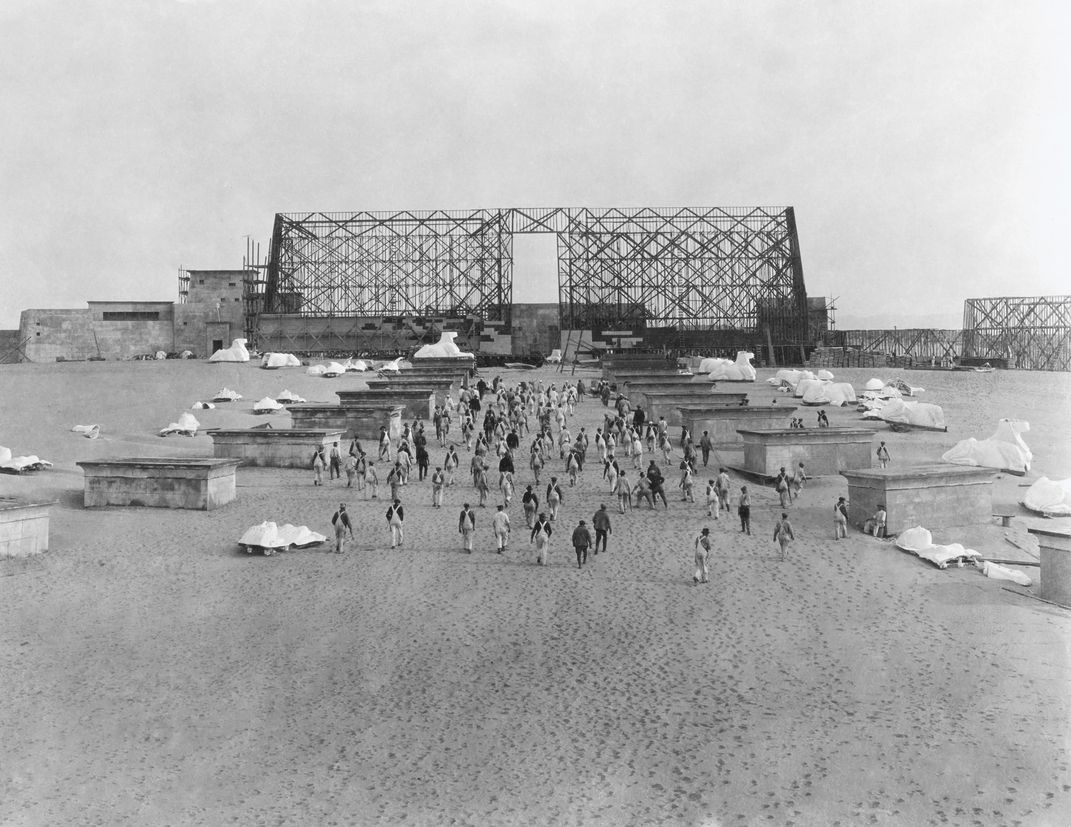

But these adventurers were not in Egypt. And most of the artifacts they dug up were made of rapidly deteriorating plaster. They had found “The Lost City” of Cecil B. DeMille in the Nipomo Dunes of Guadalupe, Calif., which the director had buried there after filming on location in 1923.

One hundred years ago, Cecil B. DeMille filmed the first biblical epic: his silent original version of The Ten Commandments. In its day, it was the largest, most popular project ever put on film. With a price tag of $1.46 million, ($26 million today), it was also the most expensive.

Following its glittering premiere at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood on Dec. 4, 1923, The Ten Commandments ran for more than a year around the country and set a box office record of $4.17 million ($74 million today), a record that stood at Paramount for 25 years. It was the top-grossing U.S. film for the year it was in release.

Among the 2,500 extras DeMille brought with him for two weeks of filming on the Nipomo Dunes were 250 Orthodox Jews from Los Angeles. Most of them, immigrants from Eastern Europe, didn’t speak English. Yet for them, the silent Ten Commandments was more than a movie. Playing the roles of their ancestors in the Exodus was emotional for them and the others on the set; during those moments, the American dream and their heritage converged.

The screenplay, by Jeanie Macpherson, is in two parts. The Exodus serves as the 45-minute prologue for a modern morality tale set in jazz-age San Francisco. Ten decades after the film’s premiere, the modern story comes off as heavy-handed and formulaic. But the prologue — even with overly theatrical performances and some anachronisms — offers visual moments that remain remarkable.

Exterior shots for the Exodus were filmed on the Nipomo Dunes of Guadalupe, Calif., 175 miles up the coast from Los Angeles. This is where Famous Players–Lasky Productions, the film production company that would change its name to Paramount, built DeMille’s colossal set for the City of Rameses.

“We believed rightly that, both in appearance and in their deep feeling of the significance of the Exodus, they would give the best possible performance as the Children of Israel,” DeMille wrote in his autobiography of the Jewish extras.

They had arrived in the United States with the great wave of Eastern European Jewish immigration. Between 1881 and 1924, approximately 2.5 million Jews fled the vicious pogroms of Eastern Europe. Pogroms are violent attacks on Jews by local non-Jewish populations. Jews languished in persecution in Eastern Europe before, during, and after World War I.

In the 2018 book, Gendered Violence: Jewish Women in the Pogroms of 1917-1921, scholar Irina Astashkevich writes that between 1917 and 1921, there were “over a thousand pogroms in about 500 localities in Russia and Eastern Europe.” Rape, she says, was used as a weapon in the pogroms in Ukraine. Over the period she researched, at least 100,000 Jews died, and unknown numbers of Jewish women were raped.

When Jewish lecturer and syndicated Jewish newspaper columnist Rita Kissin interviewed Cecil B. DeMille in April 1923 about his upcoming Ten Commandments project, she asked to be in the picture. Ever the publicist, he agreed; she arrived in Guadalupe with a contract that began, “This location is not a vacation.”

And it wasn’t. Actors huddled beneath blankets between takes, seeking protection from the Pacific winds and sandstorms. But for the immigrants, the pay was worth it: $10 a day for adults ($182 today), $7.50 a day for children ($136 today).

In late May 1923, the entire company boarded two special trains from Los Angeles. A local newspaper account of the arrival at the Guadalupe station of the first train describes “old men, infirm of step, feeble with long hair and patriarchal beards. With their belongings tied up in newspapers or in battered old suitcases, they huddled together.”

After the men were helped onto trucks and buses, the women’s train arrived, with “plump Jewish mothers, holding their little children by their hands.”

Horse-driven sleds carried them over the dunes to the tent city erected a mile from the set. These quarters, divided into companies of 50 to 100 people, would come to be called Camp DeMille. Gambling and drinking were prohibited. Men’s and women’s quarters were separated by Lasky Boulevard, named for producer Jesse Lasky, and policed by guards and deputy sheriffs. Men were not allowed in the women’s section without a pass and a chaperone.

DeMille made certain that the camp had its own synagogue, presided over by Rabbi Aaron Markadov and an interpreter, Sam Mintz, the son of a rabbi from Spokane. In one syndicated newspaper account, a Camp DeMille guide told a visitor, “See that Orthodox crowd yonder, ten languages are spoken over there.” The guide added that Mintz “is the only one that can straighten them out.”

Even so, one Jewish need had still been overlooked. On their first day at Camp DeMille, the Jews chose hunger over the ham dinner they were served.

“I sent posthaste to Los Angeles for people competent to set up a strictly kosher kitchen,” DeMille wrote. The captain of the Jewish company was permitted to choose his own cooks and make all arrangements for food.

At the wardrobe tents, the extras received their costumes, made of new material but styled to look worn and dirty.

During a fitting, Kissin overheard a conversation between two middle-aged women trying to figure out how to drape their costumes.

“Take that off’n you, Mrs. Rosen,” said Mrs. Kaplan, “or the director will be mad mit you. I’ve heard DeMille say in the olden times there wasn’t no safety pins.”

Safety pins or not, several journalists witnessed the extras at work during the filming of the flight from Egypt.

“These Jews streamed out of the great gates with tears running down their cheeks, and then without prompting or rehearsal, they began singing in Hebrew the old chants of their race, which have been sung in synagogues for thousands of years,” wrote Los Angeles Times reporter Hallett Abend.

According to syndicated Hollywood columnist Jack Jungmeyer, the Jews chanted Father of Mercy and Hear O Israel. He heard one of the older Jews say to a crew member, “We know this script — our fathers studied it long before there were movies. This is the tale of our beginnings. It is deep in our hearts.”

An elderly woman, overcome with emotion, fell to her knees, and shook a fist at the gates of Pharaoh, weeping and casting sand on her head.

Mrs. Rosen said that although she needed the money, she would have worked for nothing on The Ten Commandments.

“It’s just like living in dem times when we got the Torah, an’ now we’re going to get it all over again in a picture by Mr. DeMille,” she said.

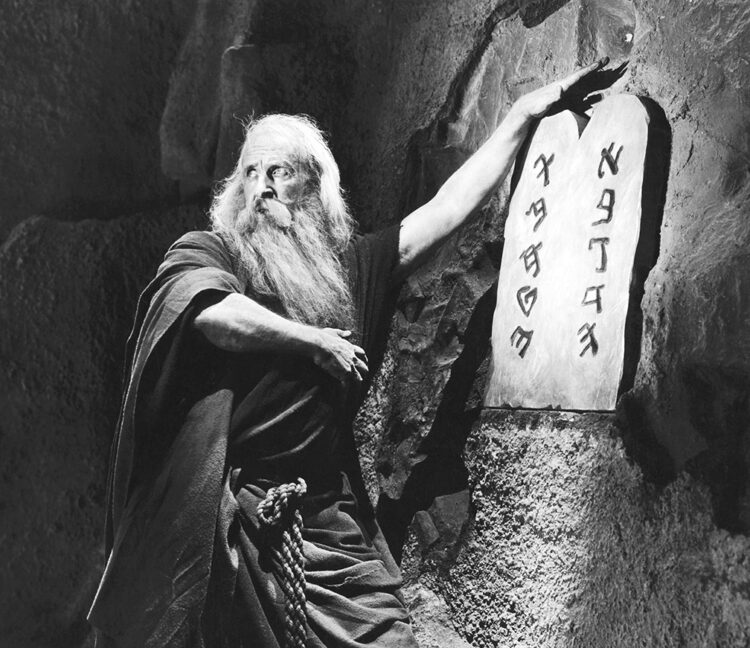

For the scene depicting the parting of the sea, actor Theodore Roberts as Moses stood on a rock at the Pacific shoreline, surrounded by the children of Israel. As sunset approached, clouds blocked out the light, threatening to ruin the shot.

“Just then the clouds cleared,” Abend wrote. “The nearly level rays of the sun made a halo around the figure of the prophet, gave a startling radiance to his face.”

“A gasp went through the crowd,” Kissin wrote. “The faces of men and women reflected this light. Tears trembled on wrinkled cheeks, sobs came from husky throats.

For many the world had moved back 3,000 years, and they stood once more on the shores of the Red Sea, viewing once more the good omen of deliverance.”

Actress Leatrice Joy was also on the set. Though she played a leading role in the film’s modern story, DeMille invited her to join the extras in the desert.

“God almighty, you never heard anything so sad as the dirge of the Jewish people,” Joy told documentary filmmaker Peter Brosnan in May 1985, a week before her death.

“They gave the impression that this was it. It was never done before. They were living the time, these people. They weren’t acting.”

“One thing in particular was DeMille’s desire to give to the screen the tremendous love that God had for the Jewish people,” Joy said. “You see, Mr. DeMille’s mother was Jewish.”

Matilda Beatrice DeMille, known as Beatrice, was born in 1853 to the prominent Samuel family of Liverpool, England. From 1920 to 1925, a cousin, First Viscount Herbert Louis Samuel, served as the first high commissioner of British Mandate Palestine. Cecil B. DeMille and the viscount shared a great-great-grandfather, Ralph Samuel (1738-1809).

After World War I, the League of Nations approved a mandate for Great Britain to govern Palestine on behalf of the league. Palestine had previously been part of the Ottoman Empire.

The mandate provided for the eventual creation of a Jewish state. DeMille’s cousin, Herbert Louis Samuel, oversaw the administration of that territory at the same time as DeMille was directing The Ten Commandments.

Samuel was a staunch supporter of Zionism. He was also the first practicing Jew to serve as the leader of a major British political party and as a Cabinet minister. It was Samuel who first suggested the notion of British support for a Jewish state, in his 1915 Cabinet memo, The Future of Palestine. This ultimately led to the November 1917 Balfour Declaration, in which Britain formally announced its support for the establishment of a “national home for the Jewish people” in Palestine. In some ways, Herbert Louis Samuel was like a modern Moses who led his people to the Promised Land.

Cecelia Presley, Cecil B. DeMille’s granddaughter, told this author in an interview that Beatrice probably came to America by herself.

The Samuel family opposed Beatrice’s budding romance with Henry Churchill DeMille, an actor, playwright, teacher, and layleader in the Episcopal Church. Even so, Beatrice became an Episcopalian and, on July 1, 1876, married Henry at St. Luke’s Church in Brooklyn.

When Henry died of typhoid 17 years later, it was up to Beatrice to support her sons, 14-year-old William and 11-year-old Cecil. She ran a school for girls and later became a play broker and agent.

It was she who introduced Cecil to Jesse Lasky; their production company was a forerunner of Paramount.

Presley said that although DeMille didn’t find out about his mother’s Jewish background until he was a grown man, he was proud of it.

She added that DeMille himself couldn’t have been Jewish “anymore than he could have been a Muslim or a Brahman.” This is evident in the Christian overtones of the modern part of the film.

It was DeMille’s father who instilled a strong sense of religion in him. Henry read the Bible aloud to his sons at night, “teaching his sons that the laws of God are not mere laws, but are the Law,” DeMille wrote.

Presley said that Beatrice’s Jewish lineage likely inspired DeMille to hire the immigrants for the movie. “No question about it, it was a very special thing for him,” she said.

“These Orthodox Jews were an example to all of the rest of us, not only in their fidelity to their laws but in the way they played their parts,” DeMille wrote in his autobiography.

“They were the Children of Israel. This was their Exodus, their liberation. They needed no direction from me to let their voices rise in ancient song and their wonderfully expressive faces shine with the holy light of freedom as they followed Moses toward the Promised Land.”

Even as the exodus had ended for these American newcomers, the gates of freedom were closing to would-be immigrants. The Immigration Act of 1924 slashed the annual number of émigrés from southern Europe (Italians) and Eastern Europe (Jews) allowed into the United States by 87%.

The U.S. State Department recorded that the purpose of the Immigration Act of 1924 was “to preserve the ideal of U.S. homogeneity.”

With the gates to the United States and so many other nations all but closed, the Jews of Eastern Europe and Central Europe would essentially be trapped there during the Holocaust.

After The Ten Commandments filming on location was completed, DeMille had the set taken apart and buried at the site, probably to save money.

Sixty years later, in 1983, filmmaker Peter Brosnan rediscovered DeMille’s lost city.

And in 2011, he secured permission and funding for the first archaeological dig in the Nipomo dunes, uncovering rare artifacts from the set. Many of the large pieces are now on display at the Guadalupe-Nipomo Dunes Center in Guadalupe.

When The Ten Commandments and its touring orchestra came to Dayton

After The Ten Commandments’ premiere at Grauman’s Egyptian Theatre in Hollywood on Dec. 4, 1923, it ran for more than a year across the United States. The hit film arrived in Dayton at the Victory (now the Victoria Theatre) on Nov. 9, 1924, for a two-week run, with shows twice daily. The movie was accompanied by a 30-piece traveling orchestra. Ticket prices ranged from 50 cents to $1.50.

In the Dayton Daily News review the day after the local premiere, James Muir declared it “epoch-making,” “prodigious,” a “masterpiece.” The film’s most impressive achievement, he wrote, was the parting of the sea.

An unsigned article in the Dayton Daily a week later noted “the picture as a whole is unquestionably the greatest achievement in the art of the cinema up to date and it has created more discussion than any book, stage play or film ever produced.”

The writer added that “many (Dayton) engineers and scientific men have viewed the picture four different times, trying to solve many of the mechanical effects that are used so effectively, such as the parting waters of the Red Sea and the giving of the Commandments to Moses on Mount Sinai.”

In The Dayton Herald, reviewer Murray Powers wrote, “All the good notices that have been given the production are deserved,” and praised its “magnificence, beauty, and greatness.”

The Herald also reported that a representative of DeMille, Lee Riley, arrived in Dayton ahead of the premiere and invited National Cash Register executives and their wives to attend the film’s opening here on DeMille’s behalf. “Mr. DeMille has always been an admirer of the NCR methods of manufacture and welfare work,” Riley told the Herald.

Brunch discussion about the movie. The Dayton Jewish Observer’s Marshall Weiss will lead a brunch discussion and partial screening of DeMille’s 1923 The Ten Commandments at 9:45 a.m., Sunday, Feb. 25 at Temple Israel, 130 Riverside Dr., Dayton. He’ll also bring items from his collection of 1923 Ten Commandments memorabilia. The brunch is a program of Temple Israel Brotherhood’s Dorothee and Louis Ryterband Lecture Series, in partnership with Miami Valley Jewish Genealogy & History, and Beth Abraham Synagogue Men’s Club’s Rick Pinsky Brunch Speaker Series. The cost is $7. RSVP to 937-496-0050 by Feb. 23.

To read the complete February 2024 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.