The Soviet spy who stole atomic secrets in Dayton

Ann Hagedorn details how — and possibly why — George Koval committed the perfect crime against America

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Five years ago, former Wall Street Journal staff writer and non-fiction author Ann Hagedorn interviewed a 92-year-old man for a story she hoped to turn into a book.

“At the end of the interview, the guy knew that I had grown up in Dayton to a certain point, and so he said, ‘Did you know that there was a secret within the secret of the Manhattan Project in Dayton during the war?’ I said no. He said, ‘Yes. It might have been near where you once lived. And a Soviet spy was involved.’”

Hagedorn, who was raised in Oakwood until she was 13, couldn’t stop thinking about what he had told her. She found the New York Times article from 2007 that reported Russian President Vladimir Putin had posthumously awarded Russia’s highest civilian honor to George Koval, “the only Soviet intelligence officer” to infiltrate the United States’ secret plants, and that his work “helped speed up considerably the time it took for the Soviet Union to develop an atomic bomb of its own.”

The world then learned that by the end of World War II, George Koval had laid the secrets of the United States’ atom bomb triggers at the Kremlin’s feet: first through his infiltration at Oak Ridge, Tenn., and then at Dayton.

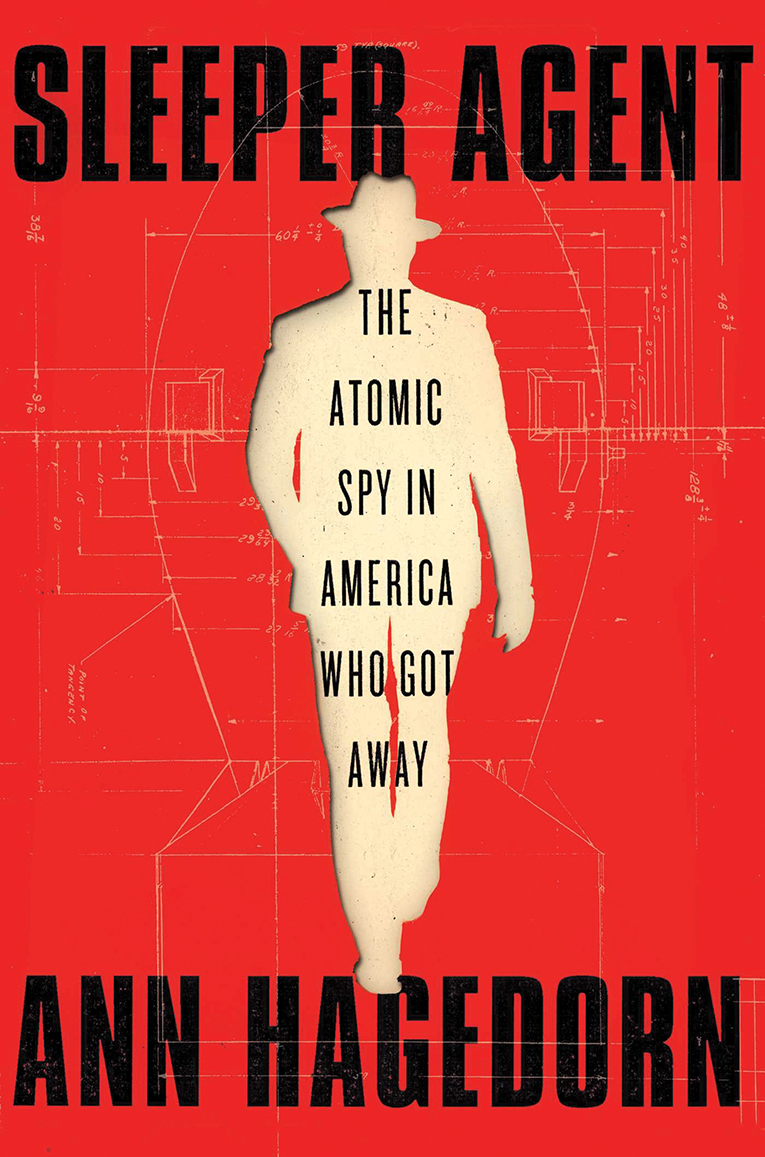

Hagedorn jettisoned the book project she was working on to learn all she could about Koval. Her extensive research — and declassification of thousands of pages of FBI files through the Freedom of Information act — has yielded Sleeper Agent: The Atomic Spy In America Who Got Away (Simon & Schuster), published in July.

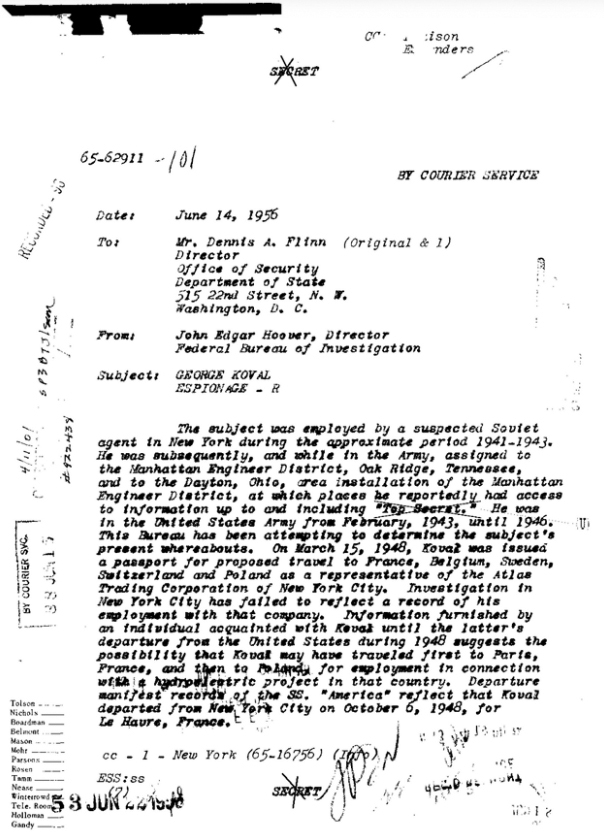

Koval committed the perfect crime against the United States; it wasn’t until 1954 — six years after he had left the United States and five years after the Soviet Union had detonated its first atomic bomb — that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI began to investigate him as a possible Soviet spy.

Koval committed the perfect crime against the United States; it wasn’t until 1954 — six years after he had left the United States and five years after the Soviet Union had detonated its first atomic bomb — that J. Edgar Hoover’s FBI began to investigate him as a possible Soviet spy.

Hagedorn, who now lives in Ripley, Ohio, focuses on the psychology of the spy in Sleeper Agent, and how antisemitism, first in czarist Russia, then in the United States, and finally in Communist Russia, impacted the choices the Koval family made.

“Being traitors to our country, you can’t honor them,” she says. “But you can recognize there was a reason for what they did.”

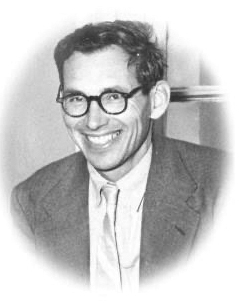

She describes Koval as a charming, accomplished, bright young man who was born and raised in Sioux City, Iowa. A straight-A student, he graduated high school at 15.

His parents, staunch secular socialists, had departed the Russian empire in 1910-11, amid its vicious antisemitism.

“And his mother’s father was a rabbi,” Hagedorn says. “She replaced Judaism with socialism. George’s parents are very active in the concept of ending world oppression, starting with ending antisemitism.”

The Kovals were part of a minority of Jews in Sioux City who had became avowed Communists by the 1920s. They were enticed by Lenin’s pledge after the October Revolution of 1917 to criminalize antisemitism and allow full Jewish participation in society.

According to FBI testimony from the 1950s, the Kovals didn’t participate in Sioux City’s organized Jewish community, with the exception of the Jewish Community Center’s sports programs.

By 1925, Koval’s father headed the Sioux City chapter of the Association for Jewish Colonization in Russia.

“The propaganda coming out of the Soviet Union was brilliant,” Hagedorn notes.

In 1931, in the wake of financial setbacks from the Great Depression and Koval’s arrest for allegedly inciting a raid at the county overseer of the poor’s office, Koval, age 17, his parents, and his two brothers left America for what would prove a brutal life of hunger in the Soviet Jewish Autonomous Region, 5,000 miles east of Moscow.

Koval’s brilliance as a college science student on the eve of World War II brought him to the attention of the GRU, the Soviet Union’s Main Intelligence Directorate.

Whether he had any choice in the matter to become a spy is not known. Correspondence Hagedorn found from much later in his life implies he may have. She believes that if Koval had a choice, he became a spy because of devotion to his family.

She points out that Koval and his wife, Lyudmila Ivanova, a member of imperial Russia’s aristocracy, had married in 1936, “shortly after the beginning of what would be known as Stalin’s Great Purge: the brutal years when millions of Russians died from executions or forced labor in the camps of Siberia.”

Hagedorn found that in late 1938 or early 1939, someone living with the couple in a Moscow apartment had reported them to the government.

“If he was a GRU intelligence officer, no matter where he went and where he died, his family would have been protected,” Hagedorn says.

After his training, Koval arrived in the United States in 1940, began his work with a cover business in New York, enrolled for the draft in 1941 under his real name, and took chemistry classes through the extension program at Columbia University.

“He goes to Columbia to mingle with scientists,” she says. “The physicists of world renown are now at Columbia.”

Because the U.S. Army needed exceptional scientists, it established its Specialized Training Program and within it, the Special Engineer Detachment.

After Koval was drafted, he achieved a stratospheric score of 152 on the army’s classification test. Koval was brought into the Special Engineer Detachment. Following a year of electrical engineering training at City College of New York, Koval was first assigned to Oak Ridge, Tenn. in August 1944, and then to Dayton from July 1945 to January 1946.

Oak Ridge and Dayton were among the more than 30 top secret sites in the United States, Canada, and United Kingdom tasked with designing, building, and fueling the United States’ atomic bombs.

With Koval’s role in the health physics department — determining radiation health hazards and developing instruments to detect levels of radiation — he had access to highly classified information and sites at Oak Ridge and Dayton.

Along with the safety protocol information he provided to his Soviet handlers, he also gave them the U.S. government’s recipe for polonium production and purification. This was the secret to creating the trigger for America’s atom bombs, the shortcut to help the Soviets successfully test their own atom bomb four years after Hiroshima and Nagasaki.

Polonium was produced and purified at the Runnymede Playhouse in Oakwood, sent to Los Alamos, N.M., and used with beryllium to fuel atomic bomb triggers.

Those with the U.S. Army assigned to the four sites across the Dayton area working on the polonium problem for Monsanto Chemical Co. wore civilian clothes.

Koval and his roommate, also transferred from Oak Ridge, lived at 1111 N. Main St. in Dayton for a month and then shared a room at 825 Grand Ave.

Koval joined a bowling league. Always one to have a pretty girl on his arm, in Dayton, he dated 22-year-old Janet Fisher over the summer of 1945. Fisher and her sister had jobs at the playhouse site that summer.

FBI documents years later indicated that the sisters lived with their parents and that Koval would play bridge with the Fishers on Sunday nights. But the girls’ mother sensed something suspicious about Koval: he would never talk about his family, and that made her uncomfortable.

If anyone in the U.S. government or military had suspicions about Koval, they could have pieced together his secret with little difficulty. But no one did. Or no one reported it.

“Hoover was right that there were these very sophisticated (Soviet espionage) networks,” Hagedorn says. “But he was so blinded by opportunism, bigotry, politics, and he was always hunting in the wrong territory — that all the spies had to be members of the Communist Party USA.

“If you were trained by the GRU and you were smart, you weren’t spending your weekends with your fellow spies. You did things like George did. Someone like George is blending in, not just with his language or with his exceptional skills as a scientist — much-needed during wartime here — but at the same time, culturally he was playing bridge, bowling.”

Koval received his discharge from the army in February 1946, turned down a job offer with Monsanto, completed his degree in electrical engineering from CCNY, and then returned to the Soviet Union in 1948.

“When he returns to Russia in 1948, there’s a huge outbreak of antisemitism. Stalin is going after the ‘cosmopolitans’ and it’s really dreadful,” Hagedorn says, noting that Koval was American born and Jewish.

Though his spying was a state secret and he had received no accolades, behind the scenes, Koval leveraged his role to receive a professorship at the Mendeleev Institute in Moscow, his alma mater.

There, he would publish more than 100 scientific papers and had a loyal student following. He died in 2006 at age 92.

His grandniece told Hagedorn that he never talked about his past. Though in 2002, when signing copies of the book The GRU and the Atomic Bomb for two of his former students, he included his code name — Delmar — the closest he came to revealing his role.

Hagedorn, who is not Jewish, notes that many of the Soviet spies were not Jewish.

“And you look at the ones who were and what you have to do is say why? The underlying theme throughout his life was the antisemitism. The backlash of bigotry is interwoven all the way through.”

To read the complete December 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.