Navigating emotional health during Covid

Absence of the human touch is hard to bear

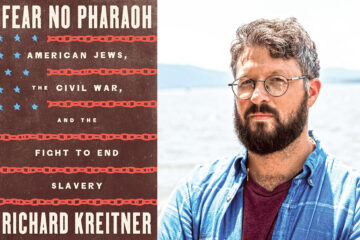

By Marshall Weiss, The Dayton Jewish Observer

Through a long fall and winter in which Jewish Family Services staff have worked to ease the anxiety, fear, and loneliness of clients sheltering against Covid, JFS Director Tara L. Feiner says she is starting to see signs of hope.

“Clients are scheduling their first vaccinations and some of them are using us for transportation to their appointments,” she says. “But we’re still seeing some ongoing anxiety. We’ve had some clients say to us that they’re just constantly in a state of anxiety about the situation. And there is loneliness.”

JFS provides transportation for its clients to medical appointments but is not yet able to meet with clients in their homes.

“People are really feeling the toll of almost a year that they haven’t seen loved ones, grandchildren, nieces, nephews, family,” Feiner says. “You can see the lack of personal touch has had such an impact.”

JFS and local Jewish clergy have been on the frontlines to help individuals feel as connected as possible — and gauging their needs for emotional support services — over the past 10 months of the pandemic.

While all agree there is no substitute for the human touch, in order to save lives, the human touch will have to wait.

“I’d love to say we’re doing all these great things, but Zoom is so not the answer,” says Temple Beth Or’s Rabbi Judy Chessin. “Having people meeting virtually is amazing but it’s not the same. What I’m learning out of all of this is just the hug and the reaching out and seeing someone face-to-face in person is far more therapeutic than I would have ever dreamed.”

Rabbi Joshua Ginsberg of Beth Abraham Synagogue says that over the last three months, Covid has begun to directly affect the community beyond the emotional and spiritual toll.

“More people have had to deal with it, themselves getting Covid or an immediate family member,” he says.

“One of the hardest parts of it is not being able to gather physically at the funeral itself in the numbers they would want, with the people they would want around them, and also, regardless of the length of the shiva, not having that gathering, and being able to just have the presence of people in all the intangible ways in which people show their care, concern, and support. That’s been really hard for a lot of people: as simple as that hug that they just can’t have.”

Both Beth Abraham Synagogue and Beth Jacob Congregation have suspended the practice of tahara — the ritual cleansing of the deceased prior to a funeral — for the duration of the pandemic.

Ginsberg says most people have “wrapped their heads” around the idea that there must be certain restrictions. Even so, it’s hard to bear.

“We’ve lost a lot of people in the community this year,” Feiner says of deaths that aren’t necessarily related to Covid. “And some have surprised us. Not everybody is sharing if someone has passed, because the grieving process is broken. No matter what your religion is. But for us, it’s not being able to sit shiva or being able to say Kaddish for those you would want to as part of a communal prayer and with community.”

Temple Israel’s Rabbi Karen Bodney-Halasz says congregants actively reach out to her for pastoral care connected to the pandemic.

“Right now, they’re especially feeling disconnected because they aren’t in constant contact with some of their friends, and so they feel like those relationships perhaps are not as strong as they had been, even though they are,” Bodney-Halasz says.

She adds that politicization of the pandemic has led some congregants to approach her for counseling.

“We’re such a divided community. Some people are taking these protocols really seriously and others are not. And so rather than sometimes engage in what turns into a conflicting discussion, they’d rather talk to someone who’s willing just to hear it from their perspective than to help them process whatever it is they’re experiencing. That’s what I’ve found.”

One congregant who views Covid through a political lens told her he thinks there’s more emotional damage happening from not gathering in person to hold worship services than he thinks would happen if people got the virus.

“And I have to say I disagree entirely,” Bodney-Halasz says. “I don’t think it’s responsible, because there are things we can do online that are filling that need that are not as risky. But for some people, they are feeling that is part of the problem. I don’t want to pretend there aren’t people feeling that way. But they are a very small minority and we’re trying to connect with them as much as we can through the phone to make sure they’re not feeling isolated.”

Congregations holding Shabbat services in person currently are Beth Abraham Synagogue, with only a minyan, the quorum of 10 required to perform public services as well as with a livestream; Chabad, which reopened in January after a month closed due to clergy who had contracted Covid; and Beth Jacob Congregation.

“We’ve been having in-person services since June,” said Beth Jacob Congregation’s Rabbi Leibel Agar. “We’ve actually had a minyan for 12 weeks in a row now. Not early enough to leyn (read Torah), but for Musaf (additional service). People come about 10:30, 11,” he said. “It’s gotten to the point that we have enough people that the only way to social distance is to use the big sanctuary. It’s not a huge crowd but it’s enough that the small sanctuary isn’t big enough to socially distance. If people weren’t responsible, we wouldn’t be able to do it.”

When the pandemic began, congregants tended to postpone their joyous lifecycle events such as Bar and Bat Mitzvahs. That was the case with the Bar Mitzvah for Ginsberg’s oldest son, Ranon. Now, nearly a year later, families tend to go ahead with lifecycles, albeit in restricted forms.

“We’ve had some Bar Mitzvahs, and we were lucky enough to be able to do so even until the last one outside at our outdoor sanctuary, so we were able to have more family members there,” Chessin says. “They sat far apart. We did an inside one (because of rain) and just had the family. What was kind of cool was that rather than having the rabbi and the kids on the bima (stage), we had the family on the bima and in essence the family did the Bar Mitzvah.”

“The mind-set began to change,” Bodney-Halasz says. “You can’t push off these important lifecycle events. You have to find a way to do them anyway and make the best of it. One couple I know has had a civil marriage and they’re going to do a big Jewish wedding celebration once everybody can get together. They had a problem finding someone to marry them civilly. They had a license, but nobody could marry them. Nobody wanted to take the risk. And they finally found someone, but it took them a really long time.”

Keeping people connected

Along with constantly calling and checking in with those on their membership/client rosters, Jewish community organizations have shifted to a routine of livestream programs to help people stay active and engaged.

“The key to our emotional and mental health is routines,” Feiner says. “Routine is key for resilience. And our routines are definitely impacted by what’s going on. The pivoting has enabled some people who weren’t able to participate in the past to join us. The flip side is there are some people who don’t join. They’re either not tech savvy or not comfortable being on the screen.”

“Their houses are probably very clean, they’ve baked everything there is to bake, they’re getting to know their spouses once again,” Rabbi Haviva Horvitz says of her congregants with Temple Beth Sholom in Middletown.

Along with the twice-a-month Shabbat services she offers on Zoom, Horvitz has added a Torah study session.

“That’s given them a strong social outlet,” she says. “It’s just a lot of fun. I’ll give them a homework assignment where there’s a certain number of parshiyot (Torah portions) to read, with instructions to focus on people: who are they meeting, what are they doing, things like that. And number two is on language. Everybody’s translation may be a little different. Why is this word being used instead of that word? They should ask questions. It’s perfectly OK to come to Torah asking questions. We started off like that, and they’re really coming out of their shells asking questions they’ve never seemed to ask. That’s been kind of neat.”

Beth Abraham Synagogue’s Cantor Andrea Raizen says her Kabba-Locked-In Shabbat program to usher in the Sabbath has helped build and sustain community since Covid hit.

“For us to have approximately 18 screens, which usually adds up to about 23 people on a regular basis is amazing, because our Friday night regular minyan up until before this all started, we rarely cracked a minyan,” Raizen says. “We had three to five people there.”

She says the program is less about the service and more about connecting.

“It’s a delightful, wonderful group of people who are so, so caring and keep up with each other,” Raizen says. “We’ve celebrated grandchildren and great-grandchildren that have come into this during this time, and people check in, and people who have been sick. It’s really been heartening to me.”

“I think folks are really trying to be as patient as they can,” says Rabbi Cary Kozberg of his congregants with Temple Sholom in Springfield. “We’ve had some of the older people that have actually had the virus, but they’re really taking it in stride. The ones who have had it, thank God, have recovered and are still taking precautions. This is actually when you see how much control we’re in and how helpless we really are. We really do have to be patient. I was part of a Torah study class last night and we were talking about how when Moses came back to talk to the people, everyone thought redemption was going to happen all at once. But it was a process.”

Congregants’ biggest fear, Bodney-Halasz says, is being alone with Covid.

“God forbid someone gets sick, knowing that, as some of the people in our congregation have experienced, that their loved ones have died, and they haven’t been able to be with them. That’s been one of the hardest things. But really, it’s the fear of just not knowing if they’re being as careful as they need to be and if they get sick, who would they possibly pass it on to?”

Since the pandemic arrived, Bodney-Halasz joins Dayton Mayor Nan Whaley’s Friday Zoom sessions with local clergy each week. Montgomery County Health Commissioner Jeffrey A. Cooper also joins the sessions.

“I’ve found it very meaningful,” Bodney-Halasz says. “Being on there with other clergy, we begin with a prayer and we end with a prayer, and we talk about the needs of our congregations and some of us, our own needs, and watching our own clergy friends go through Covid in their own homes. I feel like there’s been a lot of support in that network.”

To read the complete February 2021 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.