Bashert in the Bible

The Bible: Wisdom Literature

Jewish Family Education With Candace R. Kwiatek, The Dayton Jewish Observer

I met my future husband through a kipah-clad classmate at my Jesuit graduate school who mentioned a synagogue on a bus line. Don’t ask — it’s a long story filled with unexpected lucky coincidences.

In other words, it was bashert. After all, there’s no doubt we each found our bashert, our soulmate, in that synagogue 40 years ago.

Maybe it was bashert — divinely ordained — that we would meet. Perhaps fulfilling our destinies, our basherts, has depended in part on finding each other.

Although most often used to mean soulmate, the Yiddish word bashert encompasses various notions: a fortuitous occurrence, good luck, even an inevitable result or fate. In the traditional view, bashert connotes destiny and divine providence, the notion that everything that happens in the universe is under God’s guidance and control.

Foreordained soulmates or scripted destinies? “The fatalism implied…doesn’t sit well with Judaism’s emphasis on free will and responsibility for actions,” writes Rabbi Julian Sinclair.

This isn’t just a modern perspective; even the renowned medieval scholar Maimonides rejected such notions. “(M)any people err…with regard to many of the matters in which he is given free choice: e.g., whether he will marry a particular woman or acquire a sum of money through theft,” Maimonides writes. “God does not decree that we will perform any mitzvot…and God does not decree that we will perform any sins.”

Moment magazine author Sala Levin wonders: “How much of our life’s path is God’s decree, and how much is the consequence of personal choice?”

In response, I turn to the Book of Esther. Midway through the story, the covertly-Jewish Queen Esther learns from her uncle, Mordechai, that the evil minister Haman is plotting to annihilate the kingdom’s Jews.

Begging Esther to intercede with the king, Mordechai utters the famous line, “And who knows, but that you have come to your royal position for such a time as this?”

Was it foreordained for Esther to be queen for this exact purpose? Whether luck, destiny, or divine providence, it’s bashert that Esther is in the right place at the right time to make a difference.

But what happens next, however, is in Esther’s hands.

Bashert repeatedly plays a role in this tale. Queen Vashti is banished for disobedience, conveniently leaving an opening for Esther.

Mordechai fortuitously overhears a plot against the king, giving warning, winning the king’s favor, and ultimately becoming the king’s viceroy.

Haman builds a gallows for Mordechai, but it becomes his own destiny. Esther approaches the king uninvited, but fortunately finds favor in his eyes.

Lucky coincidences or divinely ordained? Even the rabbis of the Talmud disagree.

Clearly, however, had Esther and Mordechai not chosen to act using their own free will, the story would have ended much differently.

Throughout the Bible we find abundant evidence of bashert in its many guises. Each instance challenges us to consider: Is life destined or is it chosen, or is it a bit of each?

Adam and Eve’s destiny to work and watch the Garden of Eden seemed certain except for one small factor: God had commanded them not to eat from the tree of knowledge of good and evil, for it would lead to death. God was offering them the opportunity to choose, and in so doing, to take part in creating their destiny.

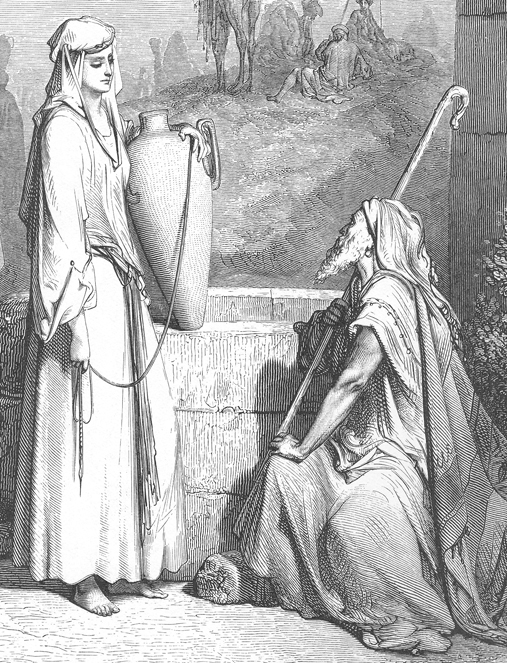

It was predictable, perhaps even inevitable that Abraham’s servant Eliezer would find the perfect wife for Isaac among his father’s kinsmen who shared history and values.

But there was no guarantee the woman would be willing; the text is clear that Rebekah was given a chance to choose.

As for Isaac, he apparently delighted in Rebekah as his soulmate, for the text atypically asserts that he loved her.

In Egypt, Joseph reassured his formerly jealous, scheming brothers, saying, “Now you, you intended me harm, but God intended it for good, in order to bring about the present result — to keep many people alive.”

Was divine providence solely responsible for Joseph’s survival, elevation to the position of Egypt’s chief minister, and reunification with his family? If his success was divinely guaranteed, what was the point of his many good decisions along the way?

Moses was destined to be God’s partner in liberating the Israelites from Egypt, but was destiny enough? The many instances of free will choices that altered the course of events suggests not.

After all, destiny couldn’t dictate the midwives’ refusal to kill Israelite baby boys, his mother’s resolve to protect him in a floating ark, an Egyptian princess’ decision to rescue the Hebrew child, or even Moses’ affirmative response to God’s call at the burning bush.

Naomi returned to the land of Judah together with Ruth, who fortuitously found herself gleaning in the fields of Boaz. Just lucky? Or preordained? Either way, their destinies ultimately depended on Boaz’s willingness to serve as Naomi’s redeemer and Ruth’s willingness to marry.

In the end, we don’t have any control over the bashert in our lives, whether we understand it as luck, fate, or divine providence. But how we respond to it, the Bible teaches, is in our control. It turns out much of our life’s path is a consequence of personal choices. It’s a sobering thought.

Literature to share

Suzanne’s Children: A Daring Rescue in Nazi Paris by Anne Nelson. France takes centerstage in this page-turning non-fiction story about Suzanne Spaak, a wealthy Brussels-born Catholic ultimately recognized by Yad Vashem as Righteous Among the Nations. Not long after she and her family moved to France, the Nazis occupied Paris and she joined the resistance, keeping her work secret from her family. Saving Jewish children from deportation became her life’s purpose because “it is imperative to do something.” Just months before the liberation of Paris, she was captured and ultimately executed. A National Jewish Book Award Finalist.

Almost Autumn by Marianne Kaurin, translated from Norwegian. Part teen romance, part historical fiction, Almost Autumn creates an authentic picture of the little-told history of the last months of the Nazi occupation of Norway. The present-tense narration, ordinary details, and multiple points of view keep the pace moving as a sense of doom builds. This young adult novel is most impactful with some background knowledge about the Holocaust. Don’t miss the author’s connection to the tale in her afterword. Haunting and well worth reading.

Related: Wedding wisdom from our rabbis

To read the complete February 2019 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.