To treat the whole patient

By Judy Bolton-Fasman, JewishBoston.com

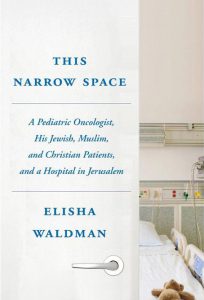

When Elisha Waldman, a pediatric oncologist, moved to Israel more than a decade ago, he was determined to make a difference in the lives of his patients at Hadassah Hospital in Jerusalem. As he chronicles in his memoir, This Narrow Space: A Pediatric Oncologist, His Jewish, Muslim, and Christian Patients, and a Hospital in Jerusalem, he appreciates that each family and each child has a unique history. He was determined to navigate physical and cultural barriers to treat the whole patient.

Waldman is now the associate chief of the division of palliative care at Ann & Robert H. Lurie Children’s Hospital of Chicago. He’ll talk about his memoir on Oct. 18 as part of the Dayton JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Fest.

What moved you to practice pediatric oncology?

As I moved through my medical studies, I was constantly interested in the sicker patients. I was drawn to oncology because it is about the whole patient — not just one organ system. In retrospect, the arc makes a lot of sense, especially from where I’m sitting now with primary palliative care. I also recognize that an interest in human suffering was driving me. How do we address suffering? How do we alleviate suffering? Oncology was a pathway to consider those questions.

What moved you to practice in Israel?

I grew up in a classic liberal Zionist home. My Dad is a Conservative rabbi and my family eventually moved to Israel from Connecticut. Right now, I’m the only family member not there. Practicing pediatric oncology was really a synthesis of all of these different things into one beautiful thing — dealing with human suffering against the backdrop of a place that is fascinating, a place I love and have aspirations for.

You write that you are drawn to treating children with cancer because of your ongoing interest in theology and humanities.

You write that you are drawn to treating children with cancer because of your ongoing interest in theology and humanities.

My undergraduate degree was in religious studies. Part of what drove me as an undergraduate was not just an academic interest in religion, but also the elements of personal challenge to my religious practice today. I deal with kids who are very sick, and I try to touch on their spiritual needs as part of a holistic approach to their treatment.

Until I started looking into palliative care, these two interests were really intertwining threads that I only recognized when I worked with the chaplains in Boston Children’s Hospital. Medicine in general is undergoing a period of change. If you look at the sweep of history, the separation of spirituality and medicine is a relatively modern event. Now clinicians are becoming more comfortable with recognizing that we need to address spiritual needs in the hospital the same way we need to address pain and suffering.

You write that, as a doctor in Israel, your “entire care management algorithm changes to adapt to the geopolitical situation.” Can you give an example?

One of the best examples is when a patient has a low-grade fever while getting chemotherapy. It’s a red flag. We instruct parents that if a child has a fever of 100 degrees Fahrenheit, they must come to the hospital no matter the time. From west Jerusalem and the surrounding Israeli areas, parents can easily get to the hospital, yet ultra-Orthodox families will often wait until after Shabbat to bring their child in.

But the real place you have to change the algorithm is where you have a Palestinian patient who you know has no immune system and will get a fever in the next day or two. Their family most likely lives in a Palestinian village miles away or a refugee camp on the other side of the separation barrier. What do I do if I think this child is going to get a fever at 2 in the morning and is not able to get back so easily? There is the reality of checkpoints in the middle of the night — a family can’t just get in the car and go to the hospital. In those cases, we would manufacture fevers to admit kids. It’s very different than practicing medicine at a place like Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center.

The JCC’s Cultural Arts & Book Fest presents Dr. Elisha Waldman at 7 p.m. on Thursday, Oct. 18 at the Boonshoft CJCE, 525 Versailles Dr., Centerville. Tickets are $5 in advance, $8 at the door and are available at jewishdayton.org, by calling 610-1555, or the evening of the event.

To read the complete October 2018 Dayton Jewish Observer, click here.